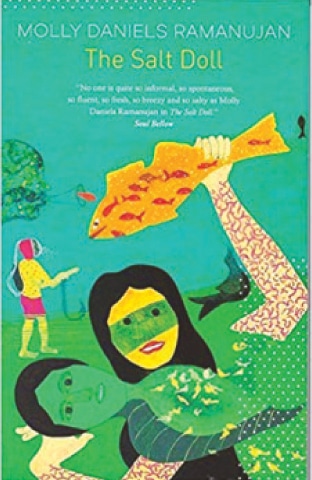

Originally published in 1978, Molly Daniels Ramanujan’s novel The Salt Doll has been reissued by Women Unlimited after 40 years. Fashioned as a novel written in the style of a memoir, the book remains as fresh and modern as it must have appeared several decades ago. Part of the reason for this is because Ramanujan was a remarkably advanced writer for her time, tackling issues of gender, sexuality, race and politics with sincerity as well as relative ease.

The novel is told entirely in the first person from the perspective of its feisty and spirited protagonist Mira Cheriyan. Hailing from Syrian Christian ancestry and based in Kerala, South India, Mira recounts her childhood and youth spent at college in the first portion of the text, and her unconventional marriage to a Brahmin in the latter portion. Her entire childhood is spent in one convent school after another and, though many South Asian authors have parodied convent life, Ramanujan takes matters to a delicious and original extreme.

Most of the nuns who oversee Mira’s education are either Indian or Portuguese and she depicts them as alternately terrifying and hilarious. At one point she goes as far as fervently wishing one of them dead. Much to our humorous horror, the nun appears to oblige by dying a week later. No stone of convent school life is left unturned by the author, ranging from the oppressively strict discipline to secret sexual awakenings stemming from a release of intense repression. Early in the novel one gets a sense of how viscerally Ramanujan writes, but though explicit — and occasionally coarse and crude — her fascination with portraying sexual matters is fortunately never gratuitous.

Reissued after 40 years, a memoir-like novel still seems fresh and emotive, but its brevity cannot do justice to its ambitions

This earthy tone pervades all aspects of her descriptions. Regardless of whether she is writing about her dysfunctional family full of mad aunts, or about her formidable grandmother, Ramanujan has a brilliant grasp over the pictorial. Images of buildings, clothing, cuisine and a pre-Second World War sea voyage to Aden, Yemen, are all conveyed so authentically that at times, it feels as if one is reading a memoir as opposed to fiction. Mira’s voyage to Aden on the SS Rawalpindi comes across as both amusing as well as adventurous. Though the novel is not strictly a period piece, it gives one a remarkable glimpse of the world as seen through the eyes of a South Indian child from the 1930s onwards, and its genuine tone may relate to the point I noted above — about it being a quasi-memoir.

Oddly cosmopolitan in nature, the book dwells on numerous races and ethnicities, including Arabs, Europeans (including, of course, the ubiquitous English), both North and South Indians, and even features a character who is an African American artist. Mira herself is very much a product of her Kerala background, but her time spent at Anand College during Partition conveys to the reader precisely how diverse and secular India itself has always been. Yet, regardless of whether she is commenting on the nefarious activities of political activists, describing the theatrical cultural milieu of the college, witnessing a beggar having an epileptic fit, discussing her forays into journalism, or mentioning the scary suicides of several of her acquaintances, Mira remains a childlike, free-spirited character, and this factor is what makes her both intriguing and strangely independent.

In spite of her intensive engagement with the physical world surrounding her, she remains less developed psychologically than one might expect. She struggles to develop a sense of identity throughout the text but, as its title implies, she is never fully successful at doing so. The title takes its name from a surreal story recounted by a spiritual sage who notes that a doll made of salt that is placed in the ocean gradually dissolves and can never retain enough of a sense of self to recount its experience in the water. Mira obviously has no problems recounting her general experiences in life, but in spite of their richness and vividness they do not appear to move her towards greater self-awareness or understanding and in this, ultimately, lies her tragedy.

The second half of the novel finds her living in the Himalayan foothills with her Brahmin husband Nanjundan, whom she refers to part reverentially and part sardonically as “the Mahatma.” Ramanujan has a way of portraying almost every major character in Mira’s life as colourful and messed up, and Nanjundan is no exception to this rule. Sexually ambiguous, yet psychologically promiscuous, he exerts a charismatic appeal over people, especially women, and Mira falls for him in a manner that is both sad and obsessive. Their relationship verges from being twistedly loving to downright abusive, but this is hardly surprising given that Mira rarely gravitates towards anything that is healthy for her.

Waist up at the window, when I see Mother Beatrice spinning around like a Spanish dancer, I let go my hold; scraping my knee, tearing my pocket, I fall on the turf below. I pick my shaken bones and sprinting across the tennis court, hide myself in the church.— Excerpt from the book

Speaking of health, perhaps the most horrific part of the book is the birth of her daughter. Full of bizarre references to Nazi sadism, the scene depicts Mira at her most anguished and dissociated and her postpartum haemorrhage adds an additionally disturbing layer to matters. Both she and the child survive physically, but there is no doubt that Mira is emotionally scarred for life by the experience. Nanjundan’s cheerful detachment does not help matters, though when one encounters his powerful, but long-suffering Brahmin mother, one gets a sense of why he prefers to objectify the female gender and why he has massive Oedipal issues.

It is impossible to remain indifferent to Ramanujan’s writing; if what she wishes to do is get a reaction out of her audience, she certainly succeeds. But though emotive and sincere, her writing lacks grace and sophistication, coming across as rather disjointed at times. Often one gets the sense that far too much material has been crammed into a mere 200 pages. This might be because — as hinted by references to literature within the text — Ramanujan hails from a literary background that relies on the work of novelists such as Charles Dickens and Fyodor Dostoyevsky among others. While this explains the author’s sound English, it also explains why the brevity of the book simply cannot do justice to material that would be better suited to a rambling, panoramic 19th century-style novel. In becoming a type of anti-Jane Eyre figure, Mira Cheriyan naturally loses all sense of identity, but sadly so does the novel.

The reviewer is assistant professor of social sciences and liberal arts at the Institute of Business Administration, Karachi

The Salt Doll

By Molly Daniels Ramanujan

Women Unlimited, India

ISBN: 978-9385606175

205pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, January 13th, 2019

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.