In August 1947 when Pakistan came into being, its founders almost immediately rushed to describe the new country as an entity which was different from India and had its own history dating back to antiquity.

Pakistan was the result of a political movement by Jinnah’s All India Muslim League (AIML) that had lobbied for a separate Muslim-majority country. The Pakistani sociologist (late) Hamza Alavi argued that the Hindu-Muslim political tensions which preceded the creation of Pakistan were the outcome of economic competition between Hindu and Muslim “salaried classes” in undivided India.

In fact, in his 1946 book Modern Islam in India: A Social Analysis, well-known British historian W.C. Smith wrote that even though many members of the Muslim middle-classes in India had done well to become bureaucrats, judges, lawyers, traders and teachers as a community, they had struggled to expand their economic status due to what they believed were hindrances being created by the Hindu majority.

Doctoring history does not help to build nations but only makes it myopic and distrustful

In a 1987 essay, Alavi further elaborated his thesis by suggesting that the Muslim salaried classes believed that the overwhelming competition posed by the Hindu salaried classes would evaporate once the AIML was able to carve out a Muslim-majority country in the region.

Indeed, the overriding reasons for Pakistan’s creation were economic and political. But the new state found it necessary to create what Ali Usman Qasmi, in a recent essay for Modern Asian Studies, calls a “master narrative”. This narrative was to explain and justify Pakistan’s creation through an overarching account which was more “historic” in nature.

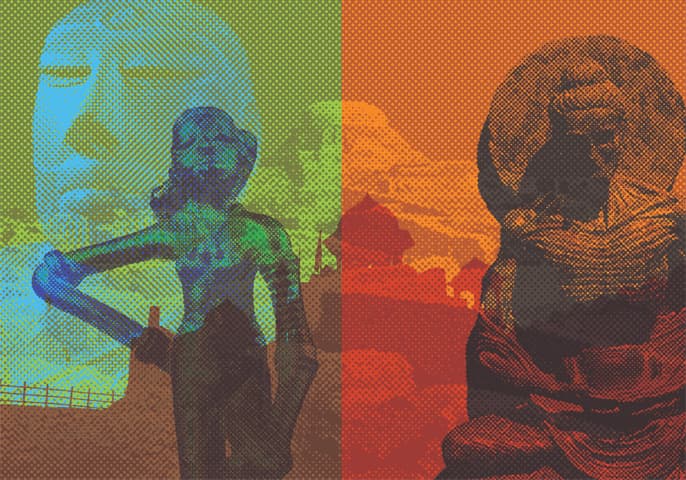

This was easier said than done. Pakistan shares centuries-old histories with a region that has become the republic of India. What’s more, a good part of this history was dominated by ancient Hindu and Buddhist rulers. Also, if the region that had become India needed to be completely divorced from Pakistan’s historical narrative, then this also meant divorcing the long Muslim rule whose epicentre was Delhi.

The challenge to carefully navigate around such complexities and yet be able to weave together a historical narrative inspired by a new country’s distinct nationalist impulses was taken by historian I. H. Qureshi. Usmani writes that Qureshi was not shy about using history for the purpose of nation-building.

In his 1962 book The Muslim Community of Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, Qureshi — perturbed that the Pakistani nationalist narrative had not been able to detach itself from the histories that the country as a region shared with India — claimed that the Muslims of India were always outsiders. He wrote that they had their own cultures and traditions and happened to rule India without being entirely absorbed by the region’s ancient social and religious currents. Therefore, according to Qureshi, the Muslims of the region were “Muslims in India” and not “Indian Muslims.”

Usmani writes that Qureshi saw the entire history of Muslims in India as a gradual process towards the creation of Pakistan. Qureshi dialed up the notion that the region’s Muslims insisted on exhibiting their separateness. He was thus critical of the inclusive policies of the third Mughal emperor, Akbar. He was also not very forgiving of the role the Sufi saints played during Muslim rule in India because theirs was not a theological creed and was thus, according to Qureshi, absorbed by the region’s non-Muslim currents.

Originally published in 1967, A Short History of Pakistan — a compilation of essays edited by Qureshi — attempted a clean break from shared histories by concentrating on the ancient histories of only those regions that had become Pakistan. This did not mean not discussing non-Muslim pasts but just non-Muslim pasts which only existed in West and East Pakistan.

In this respect, things became even more complex when, in 1971, East Pakistan broke away to become Bangladesh. Qureshi responded by lamenting that Pakistan’s “historical raison d’etre” had not been adequately communicated in school textbooks. He now offered a narrative which transcended geography. In a lecture, the historian said that countries come and go, but religions, such as Islam, stay. Thus, from 1971 onward, not only did the “ideology of Pakistan” became a compulsory subject, it was during this period that Pakistan began being referred to as a “bastion of Islam.”

When Qureshi’s metanarrative became the basis of textbooks in the 1970s and 1980s, K.K. Aziz, a former admirer and collaborator of Qureshi decided to systematically dismantle his mentor’s work. Like Qureshi, Aziz too had been a passionate Pakistani nationalist. But in the mid-1980s, distraught by the “faulty” contents of textbooks, Aziz bemoaned that Qureshi, in his enthusiasm to use history to build a nationalist ideology, had corrupted the whole process of history writing in Pakistan.

Aziz had left the country in 1978, a year after Gen Zia’s reactionary military coup. He returned in 1985 and published Murder of History in which he painstakingly pointed out the many historical inaccuracies present in textbooks being taught to students. A 2009 editorial in Daily Times says that this book had come about after Aziz “felt his growing alienation with the Pakistan nationalist narrative” — a narrative he confessed he had helped Qureshi build.

Aziz’s work flung open the opportunity for many other scholars and historians to emerge and challenge the accuracy of what was being taught as historical fact.

In Textbooks, Nationalism and History Writing, A. Muhammad Tariq writes that, by the late 1970s and 1980s, “The historical legacy of the pre-Muslim period was disowned and the physical geography of the region became irrelevant. Pakistan was no longer to seek its historical roots and traditions in the subcontinent.”

It was as if, after the 1971 East Pakistan debacle, the state had become afraid of the history that it shared with arch-enemy India. Even though this process of divorcing oneself from a shared history of a hated foe has now become prominent in BJP-ruled India as well, many post-Aziz revisionist historians in Pakistan have warned that, instead of making a nation feel secure, tinkering with history only makes it myopic, rootless and distrustful — the opposite of everything progressive.

Published in Dawn, EOS, October 28th, 2018

Download the new Dawn mobile app here: