Special report: How much does it cost to organise an election?

Elections are globally expensive, and Pakistan is no different on this count. More than the public cost, however, the liberal election spending of political parties and their candidates drives the total outlay to absurd scales.

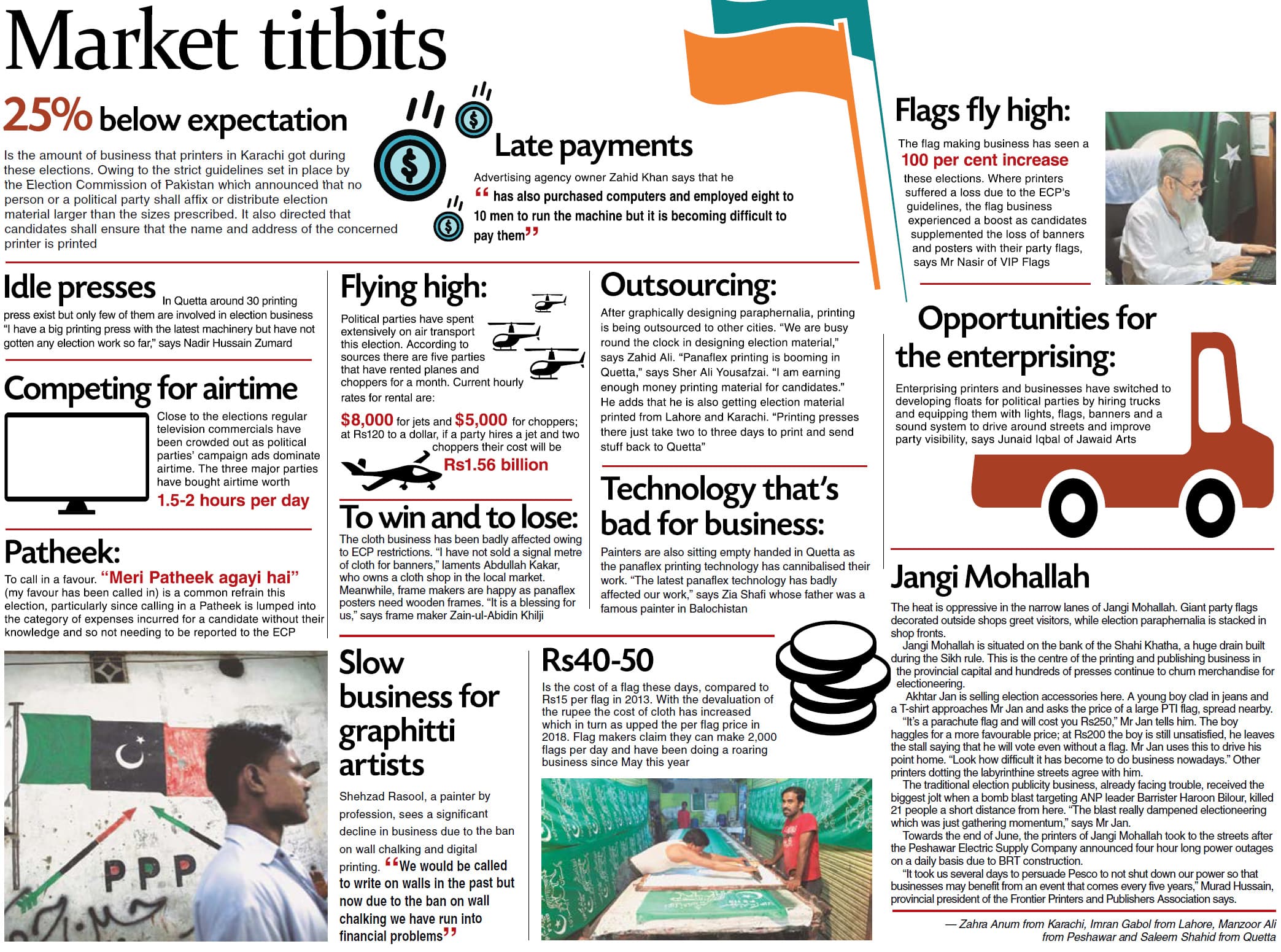

In 2018 contestants competed fiercely using all the tricks in their bags, especially money ─ oft considered the most effective tool ─ to impress constituents. From chartered planes, bulletproof four-wheelers, security details, floats, flags and feasts... the spending knew no bounds. With big money changing hands within a rather short span, it is relevant to identify the gains and the gainers.

In this special report, the Dawn Business and Finance team tries to estimate the cost and evolving patterns of electioneering that allowed businesses and services to make hay while the sun was still shining during the canvassing phase.

Gains and the gainers

As the democratic system in Pakistan evolves and reinvents itself, so does the election business.

Government spending has increased manifold with marked improvements in the regulatory framework to ensure better management of the massive exercise. The expenditure by political parties and candidates has also increased; but while this escalation was steeper in 2013, it has since moderated.

An intelligent guess puts the financial cost of the impending elections at a whooping Rs440 billion, 10 per cent higher than the total cost of the 2013 elections. The projection is a consolidated estimate, inclusive of funding from all sources — the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), federal and provincial governments, security establishment, donors, political parties, candidates and their supporters.

The share of the ECP, government and donors spending is verifiably documented and claims a bigger share of the spending pie this time around. Still, in the current projection this amount makes up hardly one-fifth of the total. It is hard to accurately quantify the budget of political parties, candidates and their supporters because of the cash component in dealings for election-related goods and services.

The lax legal framework addressing election finances in Pakistan provides ample loopholes to aspiring legislators and parties to use, or abuse, as many finances as they can muster to browbeat their opponents. The said law bars illegal avenues but ignores the most financially resourceful segment — the corporate sector. There is nothing in the relevant section of the law that realistically deals with corporate funding of political campaigns in the country.

“Money can only come from segments where wealth has been amassed. A lot of hidden wealth in Pakistan surfaces and circulates to fund electioneering, but to assume that it is sourced entirely through the black economy would simply be wrong. There is enough depth in the parallel cash-based economy to afford an activity of a monumental scale,” commented a market watcher.

“A service or material provider is indifferent to the mode of payment. If at all, they prefer cash over money transfers through banks which are recorded and liable for declaration and taxation,” he added.

“When spending runs in billions it reflects the mobilisation of high net worth individuals and entities in a country like Pakistan. This kind of circulation is hard to imagine if you take the baron/banker/broker nexus out of the matrix. It should not be hard for anyone to understand why they are reluctant to own their contribution,” he said hinting at ‘electables’ and their social circles in all parties.

Various clauses in the Election Act 2017 provide a guideline of financial conduct for candidates in an attempt to keep election spending within specified limits, but such limits are not extended to cover political parties and supporters of candidates who may pay electioneering bills without seeking candidates’ permission. Besides the specified spending limits are considered unrealistically low thereby nudging people to disregard them.

“The dissection of the election cycle provides a rare insight into the anatomy of a transformational society”

In the current Act, the ECP revised up the spending limits on candidates from Rs1 million to Rs2m for the Provincial Assembly and from Rs1.5m to Rs4m for candidates of the National Assembly. All serious candidates, irrespective of party, routinely cross the limit. The post-election filing of accounts is hardly an issue as creative accounting can save the day.

The ECP’s budget increased from Rs1.8 billion in 2008 to Rs4.6bn in 2013. For the current elections, the limit was increased to Rs21bn by the outgoing PML-N government, according to official documents and reconfirmed to Dawn by the ECP’s Director General Budget.

The spending heads of the budget included delimitation of constituencies, revision of electoral rolls, trainings, purchase of vehicles, payment to polling agents, election material, printing of ballots, security arrangements and voter education. Through simple math one can glean that the per-vote cost to the ECP shot up to Rs198 in 2018 compared to Rs58 in 2013 and Rs22 in 2008.

According to senior officials of the Free and Fair Election Network (Fafen), key drivers of the ECP spike in spending were the revised stipends for the temporary staff drawn for election duty all across the country and printing of ballot on waterproof, expensive paper, to ensure better management of the exercise.

Beyond the government and donors, identifying the money trail is not just difficult but nearly impossible owing to the cash factor. There is no clear bifurcation in resources raised by candidates and parties.

In an informal survey by Dawn, in which scores of candidates belonging to major contesting parties were interviewed, it was found that almost all candidates conducted their campaigning on their own or through resources that they themselves raised. Privately each one accepted that the spending was way beyond the specified limit.

A market survey of goods and service providers of electioneering material reinforced the perception that expenditure per candidate was indeed more than the limit.

Yet budgets are not homogeneous across regions and constituencies. Compared to urban constituencies, rural constituencies are larger in terms of geographical area and generally considered more expensive because of a lack of physical infrastructure. The transport budget is higher there. Hotly contested seats also need greater investments, particularly in certain cities of Punjab.

A closer study of campaign spending by parties and candidates sheds light on the changing composition of budgets overtime to match the demands of a fast transforming society in an age of robust electronic and social media. This evolving strategy has hurt those market players who failed to grasp the situation, while generously rewarding smart entrepreneurs. The share of many traditional businesses such as panaflex posters and banners shrank significantly whereas that of electronic media, flags and floats expanded.

In rural Pakistan, the use of bags of rice and wheat to cultivate support continued and demand for commodities increased enough to affect supplies in urban centres. Besides regular spending on running camps and offices, an additional head of managing canvassing on social media had to be incurred by parties and candidates.

According to Dawn, based on an estimate of total election spend of Rs440bn, spending per registered voter (estimated by dividing the projected election economy by the total number of voters) almost doubled from Rs2,469 in 2008 to Rs4,651 in 2013 but marginally moderated to Rs4,150 in 2018.

We now know the share of the ECP is Rs21bn, the collective share of donors and different tiers of government and security establishment can’t possibly exceed Rs19bn. Thereby, after subtracting Rs40bn out of the total Rs440bn, the residual Rs400bn falls in the accounts of candidates and parties. Legally all contestants in effect are allowed to spend Rs10 per voter (Rs4m for an average voters’ pool of 400,000 for the NA and half the amount (Rs2m) for about 200,000 voters for the PA).

“The dissection of the election cycle and assessment of election spending provide a rare insight into the anatomy of a transformational Pakistani society,” an observer commented.

The above-mentioned survey also showed that besides big-budget service providers like private aircraft and car rental companies, advertising outfits and television channel owners, the bulk of whatever is being spent has landed in the pockets of cottage industry workers contracted to produce propaganda material (badges, hand-printed shirts, caps, scarves, buntings of party flag colours, etc). A good fraction will also be pocketed by seasonal workers comprising of unemployed youth hired to man offices and work as runners.

According to candidates, as much as 50pc of the total spending is on Election Day when candidates are required to invest in mobilising and transporting the perceived support base to polling stations and facilitate their polling agents at all booths across their constituency. Voters expect provision of food and cold water bottles during the waiting time at the polling station.

It is hard to contest the fact that beyond political engineering, the regulatory and legal framework and the implementation of the code of conduct have improved. The enhanced quality of training and greater use of new communication tools will also help.

Several attempts by Dawn to solicit the position of major political parties on the gap between permissible and actual spending trends during general elections proved futile. The political leadership was either too busy close to the elections or it was avoided stating its position on the issue at this stage.

The most expensive elections

The general elections are expected to cost the federal kitty more than three times the cost of the last two elections put together. A major part of it is likely to flow to the armed forces for the deployment of troops.

The Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) is anticipating that over Rs21 billion will be spent on the process, which includes more than Rs10.5bn on the usual polling exercise, such as training, printing, remunerations, transportation and related expenses. The funds to be paid to the armed forces are anticipated to be in the same range even though final estimates will become clear after July 25 based on actual bills.

The 2008 general elections cost Rs1.84bn out of the federal budget. It surged to Rs4.73bn for the 2013 general elections, showing an increase of almost 157 per cent. The Pakistan Army was paid Rs758 million in the 2013 elections compared to Rs120m in 2008.

All these expenditures do not include expenses made by the civil administration at the provincial level, including police expenses.

ECP Secretary Babar Yaqoob Fateh Mohammad told Dawn that the major increase in expenditure was caused by imported watermarked ballot papers. Secondly, the remuneration for the polling staff has been increased from Rs3,000 (for the presiding officer in 2013) to Rs8,000 this year.

On top of that, the ECP decided to provide female presiding officers with the assistance of a peon to carry election material on the polling day, which will have an additional cost. Subsequently, male presiding officers also demanded that similar assistance be extended to them.

The ECP believes the election law is insufficient because it does not impose any upper limit on campaign expenses by political parties

Officially responding to a question, the spokesman for the ECP, Chaudhry Nadeem Qasim, said it was difficult at this stage to quantify the election cost because polling activities were spread over a period of almost a year and involve two federal budgets.

In the first year (2017-18), preparatory works were set in motion for elections, including major procurements like non-sensitive materials, imported watermark paper, stationery items, printing of envelops, electoral documents and training of election officials.

During the current fiscal year, allocations have been made for election allowances and honoraria, transportation of material and arrangements for the actual polling on Election Day. The honorarium for presiding officers has been increased from Rs3,000 to Rs8,000 this year while the same for polling officers has gone up from Rs3,000 to Rs6,000.

Following is an edited version of a Q-and-A with the ECP spokesman.

Question: Are you satisfied with rules related to the financial conduct of parties and candidates? Don’t you think there needs to be spending limits on the election budget of political parties and not just contesting candidates?

Answer: We are not satisfied with the election rules about spending limits on political parties. But the system for spending by candidates is reasonably elaborate. Under the law, the limit on the expenditure by a provincial assembly candidate is set at Rs2m. It is Rs4m for the National Assembly. Candidates are required under the law to submit details to the ECP, which is subject to scrutiny within 90 days.

For political parties, the election law is not sufficient because there is no limit on their expenses. The ECP made a number of attempts in the past to have some sort of regulation on the parties in terms of expenses, but it was overruled. This needs to be improved going forward.

To some extent, the parties are required to file their accounts to the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP). But those are not election-related and the ECP feels that there is a need for the limit on campaign-related expenses.

Question: The spending limits on NA and PA candidates are notified, but does the ECP have the organisational capacity to monitor their spending patterns to independently assess the veracity of election budget statements that they submit later?

Answer: Yes, the ECP has enough organisational capacity through a number of monitoring teams across the country — like district monitoring officers under deputy commissioners — that have only two functions to perform: whether the candidates are conforming to the code of conduct issued by the ECP and if, prima facie, their expenses are in line with the limits.

This practice has just been introduced and has many bottlenecks. But based on its experience this year, the ECP will build upon the monitoring mechanism going forward.

ECP Secretary Babar Yaqoob Fateh Mohammad told Dawn that the major increase in expenditure was caused by imported watermarked ballot papers. Secondly, the remuneration for the polling staff has been increased from Rs3,000 (for the presiding officer in 2013) to Rs8,000 this year

On top of that, the ECP has created a full-fledged political wing for the scrutiny of expenditure results and the code of conduct within 90 days. It has the powers to subsequently co-opt the services of institutions like the Auditor General of Pakistan or auditors of government departments. It can also hire specialised auditors from the private sector.

Question: Interest groups and lobbies have high stakes and use money to buy influence in elections in all democracies. Why would it be any different in Pakistan? How do you see the issue of corporate funding for political campaigns? Do we need rules to provide legal space for an activity that we know exists?

Answer: This is an issue of the election campaign and a global problem. There are a lot of shortcomings on this front. It requires legislation with the support of the political parties. This is a grey area for both the ECP and candidates. Parliament should address this issue because it has far-reaching consequences.

Question: Do you favour the introduction of the election service in the administrative setup of Pakistan to build capacity at all tiers as recommended by the monitors?

Answer: The ECP is already a specialised cadre trained at the Federal Election Academy established for the periodic training of electoral managers from federal, regional, provincial and down to the district level. For the upcoming elections, the entire staff from provincial, regional and district administration has been trained at this academy.

Therefore, it would be unwise to create a parallel cadre when the ECP is capable of working at the gross-roots level with trained district returning officers, returning officers, presiding and assistant presiding officers, polling officers and security personnel, especially army personnel who were given elaborate training. This is for the first time in the country’s history that army personnel were subjected to comprehensive training and have been given dos and don’ts.

Intricacies of pre-poll money flow

In elections, big interests clash with each eager to overpower the other. Interest groups and their proxies begin to fight: some for survival, some for influence and others to make a debut.

Understandably, all this is not possible without big money coming into play. Locally, funds are moved from one account to another. Workers and supporters of political parties abroad begin to send foreign exchange here. Part of local and foreign funds moves while skipping the banking channels, taking advantage of a network of informal money handlers. Months and weeks before the polling date, new patterns of money flow begin to emerge and become visible for trained eyes.

“A week before elections, we can see changes in money flow patterns. We’re even internally analysing them but that’s something we can’t share,” says a senior executive of a large local bank. “Information-gathering in real time, thanks to a greater use of technology, makes such patterns more obvious now than in 2013 (when the last elections were held).”

Almost all sizable banks undertake this exercise prior to polls. But they do it to evaluate the risks associated with unusual banking activities, and not for judging any particular movement of funds.

The cycle of money flow ahead of the general elections begins with the inflow of large sums via both banking channels and informal means into the designated accounts of political parties, their office-bearers and frontmen of top politicians, senior bankers say. The bulk of pre-poll expenses are then financed from these accounts.

Broader monetary indicators, like remittances and currency in circulation, don’t exhibit a big difference between their usual averages and pre-poll volumes

But this simple-looking method has lots of intricacies. Money flows are divided along the lines of illicit and lawfully earned money, local and foreign donations and funding, corporate and non-corporate money, money meant for elections but disguised as some other expenditures etc, they say.

That is why broader monetary indicators, such as remittances or currency in circulation, don’t exhibit a big variance between their usual averages and pre-poll volumes. That is also why the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) takes little interest in this issue. A standard answer of senior central bankers on pre-poll patterns of fund movements is that the subject does not merit discussion unless monetary aggregates show an otherwise unexplainable change ahead of the elections.

If you press them hard on an unusual change in the set patterns of account activities of a certain bank or a foreign exchange company, they say that the central bank does seek an explanation from the institution concerned if such a change warrants it under relevant rules and regulations. “But then, linking even such deviations to an undesired pre-poll activity without solid evidence, and in the absence of a justification to do that, is not appropriate,” says a central banker.

Take the example of home remittances. Lots of pre-poll activities are financed with foreign exchange sent by overseas Pakistanis. Major political parties that have their chapters in countries like the United Kingdom, United States, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates even begin to press their overseas office-bearers to collect and send back home as many donations from supporters as possible.

Part of this funding comes through banks and licensed foreign exchange companies. But the net amount sent back home is not big enough to show a major change in pre-election average monthly remittances. “Part of the funds that comes into Pakistan through illegal channels is also routed in manageable chunks to avoid raising unnecessary suspicion among law enforcement agencies,” according to a source in the security establishment. “Since the 2018 elections are being held amid stricter checks on money flows in the backdrop of global concerns regarding money laundering, volumes of illegal funding from abroad are not that thick.”

The cycle of money flow ahead of the general elections begins with the inflow of large sums via both banking channels and informal means into the designated accounts of political parties

But then the announcement about the tax amnesty scheme has coincided with the campaign period and holders of undeclared foreign assets have already brought back hundreds of billions of rupees. Under the part of the scheme that deals with undeclared assets within Pakistan, huge sums of black money have been whitened at the same time. “The timing of the tax amnesty scheme should raise a few questions from the point of view of financing election campaigns.”

Locally, funds for pre-election use are transferred not only through banking channels but also mobile wallets, an instrument of branchless banking. Though this instrument is very useful for the transfer of cash, the implementation of the know-your-customer regime in transactions made via mobile wallet leaves much to be desired. Officials of the security establishment say, and bankers agree, that lots of funds — segregated into smaller chunks — could be sent and received across Pakistan using mobile wallets without the banks ever knowing the true identification of fund movers.

This could have implications in terms of trailing fund movements by unscrupulous elements during the electoral process — more so this time as the use of this instrument of money transfers has grown rapidly in recent years. Here again, keeping an eye on the movement of funds meant for the electoral process financing is just too difficult. Even scanning the relevant data for this purpose becomes out of the question unless a big change in volumes of overall transactions ahead of elections comes to the regulator’s notice. “Variations in volumes handled by particular banks and microfinance banks don’t matter as much because such variations do take place as a matter of routine and for genuine reasons,” says a senior executive of a microfinance bank.

Money flows are divided along the lines of illicit and lawfully earned money, local and foreign donations and funding, corporate and non-corporate money, money meant for elections but disguised as some other expenditures etc

Given the enormity of economic problems, judicial activism and a tussle between the political class and the establishment, both mobilising and utilising funds for electioneering have been a challenge. But then, politicians always find ways for financing their election campaigns the way they plan while disregarding the limits imposed on pre-poll expenses.

Senior sales officials of a brokerage house say some of their top clients — businessmen considered close to two leading political parties — were constantly selling stocks of various companies ahead of the polls. They were diverting large parts of the money realised to accounts of people actively involved in election campaigns of the two parties.

Similarly, the owner of a Karachi-based foreign exchange company says some holders of double-accounts in foreign exchange firms offloaded their entire positions after the rupee depreciation since December last year.

“I suspect that sale proceeds in rupees are being used in elections. Since total offloading has practically emptied their accounts with foreign exchange firms, they can also avoid punitive actions for holding undeclared amounts of foreign exchange.”

How election spending has evolved over time

Over the past 70 years, the mode and range of election spending has evolved with the changing political culture, urbanisation, weakening social structures and escalating cost of communication and transport.

Top political leaders now travel by chartered airplanes and helicopters from one city to another to address election meetings. Earlier, cross-country tours were covered in special bogies of trains. Political leaders used to address wayside crowds at railway stops.

It was common for government and opposition leaders to travel by train which was cheaper and considered pretty efficient. Even donkey carts were used for rallies in Karachi for canvassing. Constituencies were small, ethical values were stronger and voters were more receptive to leaders’ narratives.

Gone are the days when ideological bias attracted social and political activists to work on a voluntary basis for a cause. Now election campaigns in urban areas are increasingly being run on modern business lines

Political parties with ideological moorings had their own newspapers which were run mainly on donations. Big money was not needed and some upper-middle class politicians even made it to parliament with only party support and mass appeal. The ‘biradari’, clan and tribal loyalties inflated vote counts.

Gone are the days when ideological bias attracted social and political activists to work on a voluntary basis for a cause. Ideology is now confined to a couple of religious parties which are better organised at the grassroots level with a very limited support base.

Election campaigns in urban areas are increasingly being run on modern business lines. As the cost of doing business is high, so are the election expenses. Only the rich in urban centres and the influential from the landed aristocracy in rural areas can afford to contest elections, having won the title ‘electable’ after winning a few polls.

Many earned this status with the government funds at their disposal for the socio-economic uplift of people in their constituency — a move initiated by Ziaul Haq. Anecdotal evidence suggests that mainstream political parties are finding it more convenient to outsource election campaigns.

Motorcyclists in Malir are offered free petrol on the condition that they fly party flags on their bikes. To do the same in a semi-urban constituency, rickshaw drivers are paid Rs100 per day. Chairmen and vice-chairmen of local bodies are given a lump-sum amount to open offices and hire men to conduct election campaigns.

Some upper-middle-class leaders of political parties are accommodated in the Senate as technocrats. Unlike in the past, political parties do not support middle-class candidates for elections to the national and provincial assemblies though they spend billions on advertising.

Election campaigns in urban areas are increasingly being run on modern business lines. As the cost of doing business is high, so are the election expenses. Only the rich in urban centres and the influential from the landed aristocracy in rural areas can afford to contest elections, having won the title ‘electable’ after winning a few polls

It is a game of big money. The three leading parties contesting the elections— PPP, PML-N and PTI—are led by rich families or supported by the wealthy. An independent political analyst estimates that a candidate would need to spend no less than Rs80 million to win a National Assembly seat, while a candidate for the provincial assembly would require half the amount.

Political parties have vote banks but proportionately dwindling numbers of political workers. They have to fall back on paid workers. Such huge expenses expose the need for these parties to cut costs by building grassroots party organisations.

But the most disturbing aspect is the huge amount of money spent on buying votes; reducing the voter-representative equation to a transactional relationship and giving currency to the charge that ours is a market-cum-dynastic democracy.

The buying of votes first emerged during the 1960s. The elections were held on restricted franchises and an electorate college of 80,000 basic democrats. That provided many rich newcomers the opportunity to buy votes and defeat some respected veteran political leaders.

Perhaps disillusioned by the performance of their representatives, many voters are also reported in several constituencies of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to have struck deals to sell votes for cash or public goods through their clan and tribal elders. Wealthy candidates are also installing solar panels, fans, water coolers, etc in community centres.

Commenting on the 2008 elections, Nile Green, professor of South Asian History at the University of California, Los Angeles, observed that none of the electoral malpractices were unique to Pakistan but “the combination and scale of their proliferation in Pakistan is exceptional.”

Massive ‘hidden expenses’ are incurred for manipulating election outcomes, much of which may not have been mobilised legally. The rigging widens the gulf between the people and the government and results in eroding social cohesion. This year, once again, two of the three major political parties— the PPP and PML-N— are complaining of a lack of an even playing field.

This means more money will go into the electoral process than the pockets of candidates may allow.

But despite hiccups things are now changing. A semi-industrialised economy and a relatively developed domestic market in urban centres is nurturing pluralism.

It is not administrative measures or judicial activism, but an active citizenry that can bring polluted politics back to its original mission of doing public good. Voters would then judge their representatives on the basis of their performance and the need for money would be minimised.

Funding political candidates

Though the new election laws enacted last year increased the campaign spending limit of candidates aspiring for a national and provincial seat, even these increased limits are not enough for aspirants to pay the bills that are an inevitable consequence of running an election campaign.

Money counts in an election even if it does not guarantee victory for the big-spenders at the end of the day.

The cost of an election differs from campaign to campaign and constituency to constituency. It largely depends on the candidate, the size and geography of a given constituency, and how fierce the competition is on a particular seat. The fact remains that even the frugal candidate ends up breaching the legal spending limits.

“In some cases, spending limits are already breached by the time a candidate leaves home to address their first election meeting,” a former Punjab minister told this correspondent on condition of anonymity. “No one is bothered about the spending restrictions. When you are in a competition, you want to win no matter what the cost.”

Pakistan’s election laws assume that candidates will finance their campaigns from their own pockets. In certain cases, particularly in the rural constituencies, this assumption holds.

“We have no favourite. The winner is our favourite. Therefore, we try to make nice with everyone and every party that matters and has a chance of coming into power”

In most instances, however, a big portion of the sum politicians spend on their election is contributed by rich individuals who sometimes are financing the top two horses in the race to ensure that their clout on state functionaries from the area doesn’t diminish.

The corporate sector, powerful business lobbies and individual businesspersons on the other hand have bigger objectives in sight when they fund the campaign of a particular candidate. They normally choose candidates with strong clout in their respective parties and are expected to be part of the next provincial or federal cabinet, and, thus, are in a position to help their financier(s) buy policy influence in the government.

Such political contributions are difficult to trace because of loopholes in campaign finance laws, and weak or lack of enforcement of the existing regulations governing such donations.

“Corporations cannot fund campaigns. Same is the case with our trade association. No company or trade lobby can legally finance politicians or political parties. They wouldn’t, even if it were lawful.

“But if you ask me, if I and my counterparts in trade contribute to election campaigns of individual candidates and political parties, I’d say yes we do. We finance them individually as well as collectively.

“The money comes from our personal accounts and is routed to the beneficiaries through informal channels. You can’t do business in this country if you do not have strong lobby in the (provincial and federal) cabinet to keep the government from making business-unfriendly policies,” argued a senior businessman who is known to have close connections with the top leadership of PML-Nawaz and Pakistan Tehrik-i-Insaf (PTI).

“We have no favourite. The winner is our favourite. Therefore, we try to make nice with everyone and every party that matters, and has a chance of coming into power. But having ‘our people’ sitting on the opposition benches also helps,” he smiled. He conceded that this strategy sometimes his strategy doesn’t pay. In such a scenario, he concluded, “we have to opt for other routes to achieve our objectives”.

A big portion of the sum politicians spend on election is contributed by rich individuals who sometimes are financing the top two horses in the race

Many, like Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (Pildat) President Ahmed Bilal Mehboob, support campaign spending limits and reducing the role of money in elections in order to ensure a level playing field for those without deep pockets or access to unlimited funds.

“We, the Pildat, also wanted the previous government to fix spending limits for political parties based on the number of seats a party is contesting. But our proposal wasn’t accepted.”

Mr Mehboob said corporations and business lobbies normally finance political parties anonymously from off-the-book sources because it was illegal for them to give political donations and could have political repercussions.

A large portion of funding comes from overseas despite a ban on foreign donations. Political parties also do not disclose the source of funding in the accounts submitted to the election authorities every year for the same reasons. “The reality is that such contributions from interest groups do find their way into the accounts of the political parties. (When the elections are over) these interest groups look for payback of their investments.”

Electioneering in the digital age

Before Election Day, democracy becomes a spectator sport of sorts. With electioneering at a fever pitch, the advertising industry, too, runs on overdrive.

On television screens — and increasingly on cell phone screens as well — an interesting hodgepodge of messages is visible: the juxtaposition of leaders campaigning passionately, but with some degree of civility, in advertisements, and often belying that in their broadcasted real-time rallies.

Somewhere, a shopkeeper whose store is closed due to loadshedding, challenges the PML-N’s claim of ending electricity outages during their stint in power. On the newspaper he is reading are animated images of PML-N Chairman Shahbaz Sharif loudly repeating his government’s now-unfulfilled promises.

The Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf’s (PTI) campaign is direct, aiming to push their point across. Though this is balanced by their solemn ads on television and in newspapers where Imran Khan pledges to create a ‘Naya Pakistan’ and shifts the focus to his achievements running the government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The PML-N offers similar ads where they remind the nation of their accomplishments, with one ad taking veiled barbs at the PTI’s persistent accusations of corruption in which a client tells his barber to change his nation by “changing the channel”.

The average air time a major political party takes up is 1.5 hours per day. For one week alone, the cost comes to Rs98 million

The PPP, on the other hand, has relatively benign messages that subtly reinforce the Bhutto connection. In their ad, a composed Bilawal sits in an aesthetically -pleasing bedroom, with pictures of him as a baby in his mother’s arms, as he narrates the PPP’s select few achievements and highlights manifesto points the party will follow if elected.

In the world of television, a one-minute advertisement during a prime time slot of major news channels costs around Rs40,000 to Rs220,000. If one considers agency discounts of 30 per cent, Geo News’ (the most watched news channel as per Gallup Pakistan) slot is worth anywhere between Rs28,000 to Rs154,000 per minute.

The average air time a major political party takes up is 1.5 hours per day. Calculating at Rs40,000 per minute, for one week alone, the cost comes to Rs25 million. And this is considering just one news channel for just one week. Experts say that the real cost runs in billions, but no political party is willing to provide a breakdown of their advertising expenditure.

According to one PTI member who deals with media affairs, the party has is no print campaign this time. A consultant from a leading advertising agency informs Dawn that political parties spend up to 10 to 15pc of their budget on advertising.

“Of this 70-80pc is allotted for Above-the-Line (ATL) advertising which includes mass media. For ATL, 50pc goes to TV, while 30pc goes to print media,” he adds.

For Below-the-Line (BTL) activities which comprise distributing banners or panaflexes, door-to-door campaigns and corner meetings, “30pc is reserved.” With an internet penetration that has grown from two per cent around the time of the previous elections to around 22pc now, social media offers a largely unregulated arena for a party to promote its agenda.

There is no control over posts on Facebook or Twitter, the main platforms for advertising. It is thus difficult to challenge the narrative being built on social media. However, the quality of production one would expect from the involvement of wealthy politicians is still lacking. For advertising and creative agencies, politics is a largely unexplored realm, one where they need to tread carefully as they themselves lack political immunity.

“Here the problem is that it is not considered public service advertising or public service product. Agencies don’t treat it as a brand but as a favour. It’s a relationship of mutual benefit. The company acts as a PR team for the party and when the party comes into power, it brings them mileage,” informs Moin Qureshi, consultant and CEO at CHQ Communications.

Advertisements for any other product, if executed properly by selecting a destination, setting aside a couple of days for shooting and using top-of-the-line products, cost up to Rs6m on an average in Pakistan, Mr Qureshi adds.

If a party employs a freelancer, the expenditure is a nominal Rs20,000 to Rs25,000. When such deals are struck, the quality of production inevitably falls drastically. The result is often poorly-thought out and executed ads, which run ad nauseam all over digital media, often irritating voters.

“The best estimate for the persuasive effects of campaign contact and advertising—such as mail, phone calls, and canvassing—on Americans’ candidate choices in general elections is zero,” alleged scholars of the University of California and Stanford University, in 2016.

Until further studies are conducted in Pakistan, it remains to be seen whether political advertisements and the billions spent on them have any substantial impact, apart from offering a unique form of entertainment to the populace.

Time to scrap the law against corporate funding in politics?

By virtue of the law, corporate entities in Pakistan are forbidden to spend on lobbying or make political contributions, which become more visible during election campaigns.

Section 184 of the Companies Act 2017 prohibits companies from making political contributions. It states: “A company shall not contribute any amount or allow utilisation of its assets to any political party; or for any political purpose to any individual or body.”

The Act goes on to warn that if a company contravenes the provisions, every director and officer who is in default shall be punishable with imprisonment of a term which may extend to two years and shall also be liable to a fine of Rs1 million.

But that scarcely deters the corporate bosses from taking sides in political lobbying for one party or the other. Politics and business go hand in hand. Enterprising company bosses are always able to find a way around the law. Cash-rich individuals and big companies provide planes, helicopters, gifts, dinners, entertainment and hard cash to party leaders.

In politics, as they say, there are no permanent friends or foes. A glimpse into how men and businesses can ditch a lame horse for the one that holds the highest hopes of winning the race was given a couple of weeks ago when a major stockbroker — who supported the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) for years and even arranged the public address system on the lawns of his bungalow for party supporters to listen to the MQM leader as he spoke from London — arranged last week a breakfast meeting for businessmen to meet Imran Khan on the same lavish lawns. Many polls suggest Mr Khan is most likely to form government in the centre.

Cash-rich individuals and big companies provide planes, helicopters, gifts, dinners, entertainment and hard cash to party leaders

The politician did mention that he was pleased to see Karachi’s business community put its faith in the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI), which was lacking previously. He also acknowledged the contribution of the person who convened the meeting and appreciated his previous generous contributions towards building a hospital and a college.

The donations and contributions to political parties do result in quid pro quo. Corporates and influential deep-pocket individuals can curry favour with politicians to influence policy issues later. The political party that assumes power would be obligated to return the favour by providing means that enable ease of doing business for such corporates. Subsidised gas and power and an assured supply of water would be possible returns to industrial-sector companies. Moreover, favours might be noticed in federal budgets and taxation regimes.

The law prohibits political contributions, but enterprising business tycoons can always find ways around the law. The money spent on such contributions can easily be concealed by adding it under various heads in the profit-and-loss account.

The Code of Corporate Governance encourages big, cash-rich companies to fulfil their responsibility to society by investing in health care, education, clean water and housing for company employees as well as deserving members of society. Companies can spend their funds in areas that are of interest to a political party to cement their solidarity. All such spending is quite ‘legitimate’.

Unless the political party and its leaders choose to forget the favours after winning the elections, the bread that corporates and businessmen cast on water most likely comes back as cakes.

A businessman from Lahore argued that it was not necessary just to back the right horse, but also to keep other close contenders happy so as not to earn their ire in case the calculations go awry. But many corporate executives said that since the law of prohibiting political contribution was almost impossible to implement, it made sense to scrap Section 184 altogether.

In many countries, companies and individuals openly make political contributions and even disclose the sum.

In the United States, for example, the US Chamber of Commerce was among the top 50 lobby spenders with an outpouring of $82 million during the last election campaign. The Big Four audit firms — Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG and Pricewaterhousecoopers — also spend heavily in lobbying and political campaigns for either Republicans or Democrats, whoever they expect to win. But all those contributions are required to be disclosed to the tax authorities.

Closer to home, Reliance Industries Chairman Mukesh Ambani, who for a brief moment last week beat Ali Baba’s Jack Ma to stand out as the richest man in Asia, is well known for his shenanigans in keeping both Bharatiya Janata Party’s Narendra Modi and Congress Vice President Rahul Gandhi happy during the Indian elections.

“Mukesh Ambani is giving money to both Rahul Gandhi and Modi — whoever forms the government, control will be in Mukesh’s hands,” said one critic, declaring it to be ‘unconstitutional’. After the elections, no charges were ever pressed against Mr Ambani or his giant corporate.

It’s a rich man’s world

Many people dislike the idea of rich businessmen parachuting into a constituency a month before the election and buying their way into the legislature.

Never mind campaign finance rules that cap spending at Rs4 million, a candidate running for the National Assembly has to spend up to five times the official limit to ensure that they stand a chance on Election Day. In other words, circumventing the law on maximum spending is at the core of the campaign exercise.

But where does all this money come from: the candidate themselves or their party? Who are the anonymous donors – or ‘personal friends’ – that benevolently let a candidate borrow their fancy Prados and gun-toting guards in speeding double-cabins trailing clouds of dust?

Most of the leading candidates for NA-244 said they had no idea how much they had spent on their election campaign until that point

Speaking to Dawn last week, most of the leading candidates for NA-244 – a Karachi constituency that stretches from Gulistan-e-Jauhar to Defence View – said they had no idea how much they had spent on their election campaign until that point.

“My accountant will have a better idea of the money we’re spending. I’m focused on running the campaign,” said PML-N candidate Miftah Ismail, who served as federal finance minister in the last government. He’s running his campaign from the head office of Ismail Industries, a confectionery business whose majority shares are controlled by his family members. His average personal income is more than Rs100m a year, he says.

The PML-N runs a nationwide campaign on TV and newspapers, but it doesn’t fund campaigns of its individual candidates. They have to arrange their own funds, Mr Ismail says. “I have never asked my party for funds. It’s also because I’m well-off and can afford to run my own campaign.” He says a typical campaign in an urban NA constituency should cost anything north of Rs20m.

He didn’t know the exact amount that he is legally allowed to spend on his campaign.

The inability or unwillingness of candidates to come up with an estimate of the actual cost they’re incurring is also because a big chunk of it is intangible. For example, the candidate for the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI), Ali Zaidi, is running his campaign from the head office of Paragon Constructors, one of the biggest construction firms operating in the country.

Sitting at the corner table in the chairman’s suite of Paragon Constructors, Mr Zaidi explained that setting up the headquarters of his campaign in an already furnished office meant he didn’t have to worry about installing a backup electricity generator or Xerox machine.

But does this not constitute a possible conflict of interest? After all, the company in question is a key stakeholder in numerous projects of Bahria Town, a controversial real estate developer fighting a number of lawsuits for alleged land-grabbing. The website of Paragon Constructors lists Bahria Apartments, Bahria Town Karachi Bridge, Bahria Town Amusement Park, Bahria Town Ali Villa and Ali Plaza as its executed projects.

Shouldn’t there be proper accounting and disclosure about who is pouring money into a campaign? Mr Zaidi agrees. “Everything can have a conflict of interest. But I’m not eyeing to be minister for development,” he said in response to a question about the possibility of his benefactor wielding influence if he and his party come to power. “Our whole fight is against this culture of nepotism,” he said while claiming that no businessman would receive any undue favour from his party’s government.

“Businesses operate on contacts worldwide. It’s about who you know and how thick your phone book is. (But) as long as you’re not breaking the law... things move on in life,” he added.

Mr Zaidi is also a businessman like PML-N’s Ismail. But his business is in the United Arab Emirates where he has been running a real estate brokerage and asset management company since 1990.

“If you ask me whether that was the only Rs8m (Rs4m for the NA seat and Rs2m for the two provincial assembly seats) that was going to be spent, then it would not have been enough. I’ll be very honest. So we have friends who donate... let us use their cars. If I start paying (for vehicles and volunteers), I’ll spend the Rs8m within a week,” Mr Zaidi said.

Like the PML-N, the PTI doesn’t provide its candidates with any funds. The campaign bus that he has rented for a month costs Rs700,000, which includes branding expenses, drivers, petrol and maintenance. Two billboard trucks cost Rs150,000 each. “That’s Rs1m gone,” he says, noting that he couldn’t afford to deploy more vehicles because he must stick to the spending limit. But the cumulative cost of the whole campaign should be around Rs20m, he says.

As for the PPP, its candidate Mian Waqar Akhtar Paganwala says his party hasn’t extended any financial support to him to fight the election. As per his estimate, he’d spent Rs2.8m until four days before Election Day and his total spending was likely to stay within the prescribed limit. However, this doesn’t account for the material support he is receiving from his friends in various forms, such as free/subsidised printing of handbills and election merchandise.

Mr Paganwala is a ‘well-established’ businessman by his own account. His net income from a 500-acre fish farm near Thatta alone is about Rs80m per year. He also owns agricultural land of 300 acres besides a mineral water plant, he said.

The Muttahida Qaumi Movement-Pakistan (MQM), which won the majority vote in 2013 from the areas that now constitute NA-244, has fielded Rauf Siddiqui for the 2018 election. He says the MQM doesn’t allow its candidates to spend their own money on campaigns.

“We’re not even allowed to pay the fee for obtaining the nomination form.” The party collects donations from the general public and spends them through different committees that report directly to headquarters, he says, adding that candidates don’t get access to any party funds.

In the years gone by, this strategy might have worked perfectly well. The party would attract massive funding from private citizens as well as businesses sympathetic to the party’s cause. But its current campaign seems to be in the doldrums at least in NA-244: the MQM has held few large public gatherings and its election camps are few and far between.

“We’ve been living under jabr (oppression) for the last three years. People are scared. But the MQM doesn’t need to spend millions. Our sympathisers may now be volunteering at the election offices of the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI), but they’ll vote for the MQM on July 25,” he claimed.

Mr Siddiqui also said he didn’t know for sure how much a candidate is allowed to spend on his campaign.

The candidate from the Muttahida Majlis-i-Amal (MMA), an electoral alliance of five religious parties, is Zahid Saeed. Belonging to the JI, he’s Managing Director of Indus Pharma, a prominent pharmaceutical company.

Like its archrival MQM, the JI prohibits its electoral candidates from spending their own money. But this doesn’t mean its candidates cannot donate funds if they’re well-heeled. “I donated Rs1.5m to my party,” he says, claiming that his campaign will adhere to the spending limit.

Outspending rivals becomes necessary for candidates that lack a basic party structure or committed workers at the mohalla level, he says. For example, a candidate in NA-244 will need up to 1,800 polling agents on Election Day. Mr Saeed claims each of his rival candidates is going to pay his polling agents some kind of stipend.

“They’re going to have hired hands on July 25. But we won’t have to spend that much because we already have a strong network of committed workers at the grass-roots level.”

Security bill skyrockets

The estimated cost of the security arrangements will be quite beyond Rs10 billion as around 800,000 security officials will be doing election duty, CCTV cameras will be installed at over 18,000 polling stations and a large number of private security agency guards will also be hired.

“The July 25 elections will be one of its kind as it has been decided that army troops will be deputed at all [85,000] polling stations as compared to the last election where army personnel were deputed at only sensitive polling stations.

“As per plan two soldiers will be inside the polling stations and at least one will be outside the polling station. However at sensitive polling stations, two to three solders may be deputed outside the station as well,” Spokesperson Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) Chaudhry Nadeem Qasim said while talking to Dawn.

With the deployment of a greater number of armed forces, expenses incurred on setting up surveillance cameras and candidates investing in personal security, the total cost of security will spike in 2018

While replying to a question, he said that ECP has not requested a specific number of troops from the army.

“We have left it to the armed forces to analyse the situation and depute officials as per their observation. Initially it was estimated that around 350,000 officials would be deputed but in a recent media briefing, by the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), it is claimed that as many as 371,000 army troops will be deputed for election duty. Moreover a large number of police officials will also be deputed at polling stations along with other security arrangements,” he said.

When asked what the total cost of security will be for the elections, Mr Qasim said that security fell within the purview of the ministries of finance and defence and that the ECP had nothing to do with it.

“The role of the armed forces will end after ballot papers and all other records have been shifted to the strong rooms of divisional headquarters. However, I personally feel that the security situation today is has improved when compared to the 2013 elections,” he said.

According to documents available with Dawn, allocation for the armed forces in the 2008 elections was Rs120 million, while the figure increased to around Rs758m for the 2013 elections.

In 2008 as many as 39,000 troops participated in security duties so that average allocation per soldier was around Rs3,076. Meanwhile over 70,000 troops participated in 2013 resulting in an average cost of over Rs10,000 per soldier.

However, because of the current rise in inflation and the increase in number of security personnel employed this year — 371,000 soldiers to be deputed in 2018 — the cost of security will skyrocket these elections.

A security analyst, requesting anonymity, supported the conclusion that security expenses these elections will be exponentially higher than in earlier elections, adding that the decision to install CCTV cameras at around 18,000 sensitive polling stations had contributed to the increase.

Talking about the withdrawal of candidate security on the orders of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, he stated that “VIPs will have to hire private guards for the duration of the elections because not only is there an actual need, but there is also a trend that people prefer to cast votes in favour of candidates that have a greater show of force.”

Secretary Election Commission Babar Yaqoob said on July 19, while speaking at the Senate Standing Committee on Interior that as many as 800,000 security staff, including the army and police, will be on duty.

Aziz Khan, senior supervisor of Vital Securities Islamabad, who is a retired army official, said that as many as 70 guards of his security agency have been hired by the army.

“They are being trained by the armed forces and will be used for security of polling stations on the day of the elections,” he claimed.

A representative of security company, VIP Bouncer Islamabad, Sajid Awan while talking to Dawn said that he has provided 10 bodyguards to different candidates for their security during the election campaigns. “Chaudhry Nadeem, who has been allotted ‘Jeep’ symbol and is contesting from Chakri, Rawalpindi, has also hired bodyguards. We have been charging Rs5,000 per day for each body guard,” he concluded.

Unique dynamics of a rural constituency

What worries a prospective candidate the most besides securing a rural constituency are the expenses to be incurred in the process.

As the electoral process gets underway, candidates start planning ways to manage an election campaign effectively with modest expenditure. Political heavyweights and independent candidates alike find innovative and expensive ways of canvassing.

With the availability of handsome cash flows they remain least concerned about expenditure. Their aim is to influence and woo voters. And in some cases candidates even pay to buy votes. Poll campaign expenses start off from setting up of ‘autaqs’ in rural areas or offices in urban settlements to monitor the election campaign.

Around 40pc of campaign expenses are incurred once the candidates get tickets, while the remaining 60pc are reserved for polling day alone

Expenses continue till polling day, the high point of each general election. Currently contesting candidates agree that 40 per cent of their campaign’s expenses are incurred once they get tickets, while the remaining 60pc are diverted towards fuel and transportation costs for polling day alone.

Every candidate saves a major chunk of their funds for this vital logistical need. In urban constituencies, one can easily ride a bike from one end to the other to bring voters, but contesting in a rural constituency is more difficult.

Besides transport, candidates initially get their stickers, leaflets and posters printed on their own so that supporters and voters may follow the trend.

“There were reports in the market in 2013 that a political party candidate spent Rs1.5 million alone on panaflexes, banners, stickers and leaflets for a national and provincial assembly seat. This is not the case this time,” says Shahid Qureshi, who composes banners, handbills and posters.

In the last two elections the trend of covering billboards with panaflex banners became popular, with a huge amount of money spent on hiring billboards andhoardings of private advertisers.

But in the current elections, restrictions imposed by the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) regarding the size of banners, flags, flexes, etc has resulted in an absence of billboards adorned with candidates’ profiles that would otherwise dot the constituency. Candidates are spending on leaflets or handbills to drive their message home.

“Our candidate from a political party utilised around Rs30m in a rural constituency during the last general elections as he had generously spent on food, transportation and other miscellaneous expenses,” says a political party activist who wished to remain anonymous.

Rs8m is required to meet polling day’s requirements of transportation, food for workers and polling agents

“ECP’s policies are unrealistic given Pakistani poll dynamics. How can an election be contested with a ceiling of two to three million rupees with present day inflation, where the dollar keeps surging and the rupee weakens?” asks a candidate.

Another candidate from a rural area of Hyderabad claims that candidates now arrange money through friends.

“Poll campaigns enable close confidantes of potential political figures to spend lavishly for them in campaigns. In lieu of this they become beneficiaries of public offices held by their chosen politicians if they win.

“They win contracts and get different businesses by using politicians’ clout in government circles,” remarks Syed Jalal Mehmood Shah, President of the Sindh United Party, who is contesting from the rural area of Jamshoro.

Shah is contesting from NA-233 of Jamshoro district, which has a hilly terrain. His constituency touches Indus Highway on one end and M9 Motorway (Karachi-Hyderabad strip) on the other. The population remains scattered and a polling station is located 10 kilometres to 20km away from populated areas.

Given present day fuel cost, the expenditure increases manifold. “There are instances in which my area’s polling station was set up in some other part which will double my transportation expenses to make sure potential voters, especially women, cast their votes,” contends a candidate.

ECP aims to increase voter turnout in elections without explaining how to ensure voters’ transportation to polling stations. This remains exclusively the job of a candidate. And If ECP’s ceiling is to be respected, argues the head of a regional party, contesting an election is impossible.

A candidate who is contesting his first elections approximates a cost of Rs10m if the election is to be fought decently. “With a budget of Rs7m to Rs8m one can meet polling day’s requirements of transportation, food for your workers and polling agents,” he asserts.

Another claims that out of their total expenditure a candidate invariably spends Rs150,000 to Rs200,000 on each polling station to cover costs of fuel, transportation, meals and drinking water on polling day. Roughly, over a 100 polling stations are set up for a provincial seat.

Transport providers have a field day by charging exorbitant rates for cars and other means of transport. Whether the ECP provide transport to voters on polling day in every constituency to lessen their financial burden, is a question every candidate asks.

Elections see more aloo, less chicken for voters

Generally, as political parties entertain voters with traditional food items at public meetings ahead of polls and in the vicinity of polling stations near Election Day; both food businesses and commodity markets witness a boost.

Since the 2018 election campaigning period has coincided with the month of Eid, in which lots of weddings are held, food businesses were expecting an exceptional rise in demand this year. But that did not happen.

Higher prices of food commodities and a stricter enforcement of electioneering code of conduct have apparently moderated expected demand, owners and managers of food businesses say.

Higher prices of food commodities and a stricter enforcement of electioneering code of conduct have apparently moderated expected demand

Traders at Jodia Bazar (one of Karachi’s oldest markets) say prices of almost all food commodities have risen either due to the direct impact of a recent rupee depreciation, or as a result of the inflationary pressure building up in the domestic economy. This has led to a slower than expected growth in bulk sale of rice, sugar, pulses and spices during this time of the year.

Besides, doubts created regarding the elections even taking place — owing to the tussle between political parties and the violence perpetuated ahead of the event — impacted forward sales of food commodities in the second half of June, traders at Jodia Bazar point out.

“I was expecting huge forward sales of rice, pulses and spices after Ramazan for delivery during the upcoming Eid and ahead of polls but well, I can say that the actual demand turned out to be just half of what I had expected,” says a leading trader at Jodia Bazar.

“Semi-wholesalers in the city to whom I supply food commodities may have had a better idea of the demand pattern during the upcoming elections, which is why many of them booked smaller amounts of food commodities in June.”

As confidence about the certainty of the July 25 polls increased towards the end of June, semi-wholesalers began purchases of food commodities from Jodia Bazar to buildup their inventories ahead of elections and amidst the ongoing wedding season.

This continues but after another rupee depreciation of 5.7pc on July 16 prices of commodities have suddenly increased, retailers and semi-wholesalers complain.

Despite the rate hike, food caterers that make direct and often advance purchases from Jodia Bazar say they continue to book orders for biryani, qorma, roti and zarda to be served at candidates’ corner meetings or the local offices of their political parties.

At these offices, food is served regularly to party workers and supporters that have started frequenting the offices ahead of elections. “But these elections are somewhat slower than 2013,” remarked Muhammad Owais, owner of a local food business at Nagan Chowrangi, Karachi.

Political parties with proactive social arms are also attracting voters via social welfare platforms and are organising events like picnic parties, social get-togethers and collective prayers for this purpose. On such occasions food and drinks are also offered.

Owners and managers of food catering houses in Saddar, Burns Road, Nazimabad, Liaquatabad, Federal B. Area, North Karachi, Malir, Gulshan-i-Iqbal, Gulistan-Jauhar and other parts of Karachi say many of them are supplying one to three daighs of biryani to the local offices of political parties daily.

The number of daighs of biryani served at the corner meetings of electoral candidates goes up depending upon the size of these meetings and the budgets of those who arrange them. In case of smaller meetings this number ranges between two and five, caterers say, adding that at larger corner meetings they have served five to 10 daighs as well.

The trend of serving food to political workers, supporters and prospective voters during campaigning is common everywhere in Pakistan but this time its reportedly gathering more momentum in Sindh and Punjab.

In KP and Balochistan, extreme pre-poll violence has somewhat dampened the spirit of campaigning.

Meanwhile, dealers complain of disruption in inland transportation of commodities because of roadblocks, clogged vehicular traffic and shortage of trucks and vans which are being hired to transport people to public meetings.

Traders with low inventories in Karachi are finding it difficult to augment the same with supplies from interior Sindh and Punjab. This, along with the increase in transportation charges on the back of higher fuel oil prices, is also a reason for the spike in prices of food items.

Rice supplies generally begin to thin out at this time of the year ahead of harvesting of the new crop from August-September; “but (due to the facts stated above), these supplies have almost come to a halt and our inventories have depleted faster than they normally would,” laments Muhammad Zulfiqar, a rice dealer based in Karachi.

Another noteworthy development is that the supply of food grains and vegetables to city markets has been affected owing to the increase in food offerings by political parties to their rural supporters.

The trend of serving the comparatively cheaper chana (chickpea) biryani and aalo (potato) biryani to workers of political parties at their local offices, particularly in financially modest localities is evident during these elections compared to the 2013 elections.

With an already flawed price monitoring mechanism, the deputation of price magistrates on election duties has given retailers, including those dealing in chicken and meat, a freer hand to overcharge customers, media reports suggest.

Big cars lead the charge

As the country gets closer to Election Day, the business of vehicle rental is booming.

While it is hard to quantify the boom as estimates differ among dealers, a consensus hints at an increase of around 70 to 100 per cent compared to the last elections.

Car dealers identify two new trends, particular to the current elections, in their business: an exceptionally high dependence on four wheelers and Pakistan Teheerk-e-Insaf (PTI) candidates leading the charge in hiring vehicles.

While it is hard to quantify the boom as estimates differ among dealers, a general agreement hints at an increase of around 70-100pc compared to the last elections

“Over 95pc demand is restricted to three brands — double-cabin Vigo (commonly known as daala), Prado and Land Cruiser jeep — as they have emerged as a symbol of political and financial power,” explains Samad Hussain, a dealer who has been in the business for the last two decades.

Small vehicles — such as 1,300CC cars — are almost out of vogue these days as they have no electoral appeal.

Rental rates of flashy brands have doubled, even tripled, in the last two months.

For example, a double-cabin Vigo, which was available for a rent of Rs250,000 per month in May, has currently gone up to around Rs840,000 per month (Rs28,000 per day) while the rent for a Prado has increased from Rs450,000 per month to approximately over Rs1 million per month (at Rs35,000 per day).

Land Cruiser, however, is leading the way at Rs1.5m a month (Rs50,000 per day) — up from Rs750,000 per month in May.

“Over 70pc of this demand in Lahore has come from PTI candidates,” claims Shamraiz Hassan, who has also rented vehicles to election contestants. He gave the example of one rich PTI candidate, contesting through many constituencies in the city, as being primarily responsible for this spike in Lahore business.

“Secondly, the PML-Nawaz people are old hands at electoral politics and mostly have the vehicles they require during electioneering. They are not falling over each other for vehicles like the PTI candidates, but they have certainly driven the demand up by around 20pc,” Shamraiz continues.

One can say that independents are making up the left over 10pc of the demand. There are certain parties who have not approached the local market to rent any vehicles. These parties may be using self-owned vehicles or they may not be using any big vehicle at all, either way they have not been out there in the business of hiring so far, he concludes.

“Lahore has a very limited number of big vehicles and the gap in demand is being met by vehicles coming from other parts of the country, especially KP,” Sheikh Shabir tells Dawn. The city dealers only had 120 such loaded vehicles (Prado or Land Cruisers) because very few people can afford massive rentals.

Supply during the polls comes either from some relatively less-endowed candidates who sell their vehicles to fund their election campaigns, or from KP where such vehicles are available for a relatively cheaper rate because of low demand.

Dealers from Punjab hire these vehicles for a longterm well before elections. This year a major supply of the double-cabin jeep came from Lakki Marwat, where it was available for Rs150,000 per month as compared to Rs250,000 per month in Lahore — dealers therefore made around Rs100,000 per month in May, which has skyrocketed to around Rs800,000 per month, he reveals.

Comparing rents this year with the 2013 elections, Samad Hussain says “we used to charge Rs170,000 for the double-cabin vehicles back in 2013, Rs370,000 for a Prado and Rs650,000 for a Land Cruiser. Now, they have jumped to the levels quoted earlier.

“Apart from a rise in business, there are a number of other reasons for the increase in rentals: general inflation, continued slide in value of rupee as compared to the dollar and the resultant increase in cost of vehicles.

He, however, does not think that people in the car rental business make any fresh investment on vehicles especially for the elections.

“The price of these vehicles goes up by 20pc to 30pc as elections near and settles back down once they are over. The difference between pre- and post-elections prices is large enough to neutralise potential profits.

On top of this, renting vehicles out during elections is not a smooth proposition. The use of vehicles is so rough that it not only multiplies the maintenance cost but later repairs also cost a fortune.

Retrieving money from the candidates after they have won the elections is also a herculean task, and almost impossible if they lose. It was for this reason that this year it was decided at the level of the dealer’s association that payments would be charged in-advance to minimise the risk of sinking rentals.

On the streets of Karachi

It is kind of funny how time and time again anything and everything you put across to the man on the street evokes sarcasm — blanket sarcasm. Most of them subsequently try to be rational but that is more of an afterthought. Initially you almost always get a knee-jerk response. They don’t just try to laugh off the question. They pretty much do the same to the questioner.

From small-time vendors selling their wares in upscale areas to their counterparts in downtown, middle-class and peripheral localities, the streak remains unchanged on Karachi’s streets.

When camera crews of television channels approach them for footage and sound bites, people behave slightly differently for they know their faces will be beamed across the country and beyond, but only if they are politically correct in terms of word choice.

Yet when you approach them with just a pen and a notebook in hand, Karachiites speak their own language, which is rather colourful and dotted with expletives.

For Karachi and Karachiites, this year’s election is a new phenomenon. They actually have to think. The last time they did that was in the 1977 elections

It is fun interacting with them, but the fun soon ends for there is hardly anything left to cobble up a copy worth publishing. You come back to your desk with nothing on the notebook and a load of (self-) censoring beeps crossing your mind and asterisks dangling in front of your eyes.

How is the election campaign going this time round? It was a simple how-is-the-weather-type question. At least it was intended that way, but pat came a counter-question. “First you tell me how much money is being spent on all this.”

When told that in the last elections, it was about Rs400 billion and was likely to be no less this time, a few inventive curses preceded a stare — as if you were the one spending all that — and then came this gem:

“How much do you think will be enough to build the Bhasha Dam that we are about to build with the help of the chief justice? The Election Commission of Pakistan should have asked all the candidates to donate to the fund created for the purpose. That would have been much better than spending on trucks wrapped up in panaflex and fitted with sound systems blaring out self-conceived, self-written eulogies in self-praise …”

One of the major slogans coined for Imran Khan, who is contesting a National Assembly seat from Gulshan-e-Iqbal, is ‘Wazeer-e-Azam Karachi Se’, which aims at providing some sort of assurance — if not incentive — to Karachiites that they will be decently represented in parliament if they vote for him. Many would have felt convinced, but not everyone seems to be on board.

“There was another prime minister from Karachi. Liaquat Ali Khan. Remember what happened to him? I hope nobody meets the same fate, but, well, you never know. Do you?”

The twinkle in the eyes and the gesture of the hands said a bit more, but let’s leave it at that.

For Karachi and Karachiites, the election this year is a new phenomenon. They actually have to think. The last time they did that was in the 1977 elections. Since then, everyone knew who was going to take Karachi.

That element is missing this year, which means it is a city pregnant with hope and uncertainty. For many, it is a case of being pregnant with twins, and mood swings are pretty much part of such a phase.

While talking to a vendor in the city’s central district, it just so happened that a truck passed by with the election symbol of a dolphin prominently displayed. The gentleman concerned left his discourse midstream, winked and said what he probably could not say in the past.

“The dolphin, you see, is an apt symbol. It’s the Indus Dolphin, actually, and you know it is an endangered species. Let’s see if somebody can come to its rescue.” The next thing he did was a high-five with his friend standing next to him. The truck passed, but the laughter continued a wee bit longer.

Postscript: All the quotes above represent the most sanitised versions of long rambles, but if you don’t live in a world of your own, it is actually not too difficult to pick the (self-) censoring beeps and asterisks that are invisible and yet there in the text. Try again, if you will.

Letter from Mumbai: No questions asked about corporate funding

While India boasts of being one of the most vibrant democracies with a highly transparent electoral system, followed by a smooth takeover of power; where political party funding is concerned it is one of the most regressive countries in the modern world.

Political parties including the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the opposition Congress — along with their respective followers and backers — have steadfastly refused to bring in legislation to regularise electoral funding.

In fact, just a few months ago, the Lok Sabha, the lower house of Parliament, quietly passed a bill that exempts political parties from scrutiny of funds that they have received from abroad for the past four decades.

The lower house passed an amendment to the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010 (FCRA), overturning a key aspect that banned overseas corporations from funding Indian political parties.

Ironically, even the Congress and other opposition parties, who were vociferously opposed to the passing of the Finance Bill 2018 in parliament, did not appear to be unduly concerned with the government moving the amendment to the Foreign Contribution Act.