AS proceedings on mega real estate schemes continue in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s May 4 verdict, the debate in the media on its possible impacts is inadequate, and lacklustre economic indicators means that most stakeholders re-subscribe to land and real estate as their only reliable investment options. From an urban planning and environmental management view, this is highly damaging. Land is a finite asset that can only be used for public benefit, which is best determined through a professionally and socially appropriate planning process.

A sustainable urban life cannot be contemplated without a proper land utilisation policy with detailed master plans outlining proposed functions in relation to existing constraints and potentials. Given Karachi’s on-going infrastructure, governance and urban management crises, it is crucial that any new venture be examined for its operational viability and sustainability in the short and long term. Right now, the caretaker government (though constrained in terms of time, powers and mandate) may consider certain steps to correct the course of land management.

The first step is to empower the planning process. The city needs an autonomous planning agency with jurisdiction over the entire Karachi division. All the city’s past master plans called for such a body. Ironically, previous governments have made the planning department subservient to the building control authority, which is against standard norms. Building control bodies follow the prescriptions of master planners — not the other way around. All major institutions of federal and provincial governments, military authorities related to land management, infrastructure management bodies, private sector and civil society should be represented on its steering committee. It is certain that a potent planning agency, with the authority to supervise execution of its plans, will be able to effectively address many issues.

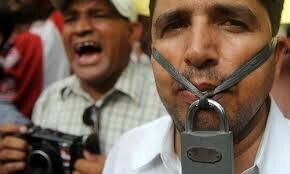

Corruption and malpractice in land management schemes arise from a number of factors. The provincial government’s centralised control over land, with no accountability to its people, is one reason. Historically, chief ministers allot and allocate lands to benefit cliques among their parties or extended affiliates. Attempts to research and highlight land issues are met with strong-arm tactics. Nisar Baloch, who campaigned to protect public land in SITE, was murdered in broad daylight in 2009. Perween Rahman of the Orangi Pilot Project was killed in 2013 for her work on the urban poor’s land access challenges. Many other activists, journalists and researchers face intimidation and threats when they work to survey and analyse our land disposal dynamics.

There is no sustainable urban life without land management.

A useful solution to some of these problems is to have a public online land repository, containing data on land ownership, dimensions and area, transaction history, revenue and taxation, as well as current status. The provincial government made a similar but inadequate attempt; it must be comprehensively updated. Experts believe that public access to land and property information can substantially reduce corruption and malpractice.

Our land policies do not reflect a range of quasi-legal situations between formal and informal housing. Land or housing that is formally registered through registrar offices, and that can be accepted for mortgage financing, are recognised as legal properties. Spot field studies show that there are many lacunae where units fall short of meeting these two conditions.

Plots floated in a development authority scheme, legally constituted cooperative societies or any other land-owning agency are termed as formally titled land. The legality of such land parcels is only accepted when the leasing conditions of the concerned neighbourhood/locality are fulfilled. Some types that cannot be compared with normally leased land include: katchi abadis that have been approved for regularisation but await initiation of the leasing process; neighbourhoods that await notification of amelioration plans; localities where change of land use has taken place; and areas that have a change of status or jurisdiction.

Owners and prospective buyers suffer due to the indifference of planning and development agencies, while powerful groups acquire such properties at lower prices and harass stakeholders (including legal heirs) to submit to their demands. Delivery mechanisms are so designed that speculation automatically evolves in the process, as civilian and military land development agencies allot land at a very low selling price. Regulatory controls, such as non-utilisation fees, are either unenforceable or too miniscule to bother property owners. A capable and independent planning agency at the metropolitan level has the potential to tackle many of these issues on a sustained basis.

The writer is a professor and dean, Faculty of Architecture and Management Sciences, NED University, Karachi.

Published in Dawn, July 5th, 2018