ISTANBUL: When Iran’s worst unrest in years broke out in December, the country’s president, Hassan Rouhani, saw a rare chance to push for reform.

Rouhani had won a second term last year campaigning on a platform for change. But he faced stiff resistance from the country’s hard-line clerics, who wield the ultimate authority. So as Iranian protesters, furious over political repression and a stagnant economy, took to the streets for nearly two weeks, Rouhani leveraged their anger to promote his agenda.

Since then, he has increased pressure on Iran’s armed forces, including the powerful Revolutionary Guard, to divest from the economy. And he has made moves to overhaul a chaotic banking sector, where illicit lenders wiped out the savings of small depositors, helping stir the unrest.

The president has publicly sided with the protesters and urged his rivals to heed their calls.

“People have criticism and objections on the economic issue and they have a right. But the objections aren’t only economic,” Rouhani said at a televised news conference earlier this month, according to Reuters. “They also have something to say about political and social issues and foreign relations. Our ears must be completely open to listen and know what the people want.”

The sentiment has registered with the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who on Sunday acknowledged the criticism and said officials were “well aware” of the issues plaguing the country.

Amir Handjani, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Centre, said Rouhani “has gone further than any Iranian president” in advocating for political and economic reforms. “He has pushed back on the notion that all protesters are seditionists, he has given them space to air their grievances, and he has said they have a right to question their leaders,” he said.

But Rouhani, who is both a pro-reform leader and government insider, “is still limited in what he can do because of how the Iranian system works”, Handjani said, pointing to the power of Khamenei and Iran’s Guardian Council, a body of theocrats that has the final say on all matters of the state.

Still, Rouhani has successfully steered the debate.

In recent weeks, he has repeatedly called on state entities to unload their assets and make way for the private sector. The Revolutionary Guard, in particular, maintain a sprawling network of businesses in everything from energy infrastructure to telecommunications, and play an extremely influential role in the economy.

“Rouhani has pushed Khamenei to recognise the Guard’s opacity and corruption has hampered growth,” Henry Rome, Iran researcher at the political risk firm, Eurasia Group, said in a briefing note. “The Rouhani administration has twice in recent weeks called on powerful state and semi-state institutions . . . to halt or reduce their business activities.”

Last month, Defence Minister Amir Hatami said in an interview that Khamenei had assigned the General Staff of the Armed Forces to oversee the exit of Iran’s military forces from “irrelevant economic activities”.

Rouhani, too, has taken on the unregulated lenders, whose spread he blames on his predecessor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Rouhani announced last month he had instructed the Central Bank to stop issuing permits to new private banks. In a televised interview, he also said the Central Bank has spent roughly $2.5 billion to bail out depositors.

But even as he has stirred hopes for reform, a string of economic and political crises has threatened to hinder progress.

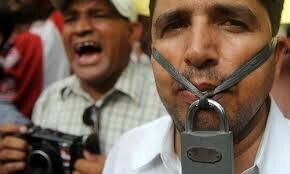

In recent weeks, Iran has experienced continued unrest. Women have staged demonstrations in Tehran and other cities to publicly remove their headscarves, which they are legally required to wear. Earlier this week, five security personnel were killed in the capital following clashes with members of a Sufi order, who had gathered outside their leader’s home over fears he would be detained.

And workers and pensioners have continued to stage small-scale protests for unpaid wages and benefits, including at major construction firms, a sugar factory and outside the ministry of labour.

Iran has also seen the high-profile deaths of detainees in prison, including a prominent environmental activist who died in prison just days after he was arrested, and the rapid descent of its currency. The Iranian rial, already battered by US sanctions, depreciated 13 per cent from late December to early February, hitting record lows against the dollar. The rial has since strengthened, but not after police in Tehran detained as many as 100 unlicensed currency traders who officials say helped push the rial down.

“Iran is in bad shape,” said Farzan Sabet, a fellow at the Graduate Institute’s Global Governance Centre in Geneva. “The economy is stagnating. Young people are having trouble finding work . . . and retirees have seen their savings in mismanaged and corrupt credit institutions go up in smoke.”

The fits and starts — and what some critics see as Rouhani’s failure to curb the state’s excesses — have prompted some of his pro-reform allies to split with the president.

Mostafa Tajzadeh, a leading reformist, said in a recent interview with the Iranian Labour News Agency that the “transparency and candidness” Rouhani showed during his campaign “can no longer be seen”.

“I believe Rouhani is smart enough not to turn toward the right, because he knows he will lose the support of the masses if he does,” Tajzadeh said. “Rouhani has to be careful with this,” he said.

In parliament, reformists and conservatives alike have pushed back against Rouhani’s proposed budget for the Iranian fiscal year. That budget, which was leaked to the news media in December, envisioned steep cuts to state subsidies and was a spark for the unrest.

But Mohammad Ali Shabani, editor of Iran coverage at the Al-Monitor news portal, said the president still has the power and opportunity to enact change.

“Rouhani could have in his hands his perhaps greatest chance to confront the vested interests preventing his agenda for reform,” he said. “He certainly has a clearer public mandate for change given the public pressure.”

—By arrangement with The Washington Post

Published in Dawn, February 26th, 2018

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.