The past June in Karachi, temperatures soared to 47.2 degrees Celsius (117 degrees Fahrenheit) with 94 percent humidity, resulting in scores of deaths caused from heatstrokes alone. These catastrophic statistics are equal to any crisis the city of Karachi has witnessed.

As architects, a recurring question for us is why our buildings aren’t designed to withstand harsh temperatures. More importantly, why do we fail to capitalise on our natural resources, such as the sea breeze and subtropical conditions that nurture greenery and are favourable to our thermal comfort? In fact, due to the lack of ventilation and poor insulation, building interiors are comparable to a hot oven, baking its residents in the hot climate.Our built environment fails, both at the level of choice of material and design, which results in buildings that are not suited for the health and well-being of the end-users.

With this constant query in mind, while visiting a friend at the University of Karachi (KU) campus, we toured the Mahmud Hussain Library (See photograph 1) and the surrounding buildings for the first time. We were fortunate to see the architectural works and perhaps one of the best design solutions for the harsh climate, designed by a master of Modern Architecture, Michael Ecochard (March 11, 1905 — May 24, 1985). In line with the great Modernists of his time, Ecochard was the contemporary of the great architect Le Corbusier and followed very similar Modernist principles. Commissioned by the Government of Pakistan, Ecochard was the original architect for the Karachi University master plan and campus buildings from the 1950s. Karachi at that time was the capital of the newly born country and the location for the new campus had a specific requirement: to be located outside the city limits. At that time, the electric power grid had not reached the proposed location, presenting a challenge for Ecochard to design the campus for the city’s hot weather, and provide a comfortable environment.

A renowned French architect’s innovative design transformed the KU campus into an oasis in the scorching Karachi heat

Located in the centre of the campus, the initial impression of Mahmud Hussain Library reads as a grand modern structure of a bygone era, ageing gracefully. It is a six-storey concrete structure elevated on a podium, with sculpturing supports for ramps and stairs connecting to the surrounding site (see photograph 2). On the exterior, the building envelope has deep recessed windows, balconies and sun-shades. The interior has high ceilings and double height spaces, interconnected through balconies. But what makes this building more interesting is that the interior spaces are naturally ventilated, without any help of A/C units, and are filled with the daylight, making the space light and airy. (See photographs 3, 4 and 5)

Hence, one visit to the library turned into a three-year long quest of documenting and researching Ecochard’s work in Karachi. The idea behind Ecochard’s design for Karachi University became more evident through this process of survey, research and documentation.

With the encouragement of urban planner Arif Hasan, head of department of Visual Studies Durriya Kazi and assistant professor of history at KU Dr Moiz Khan, as well as the assistance of fourth-year architecture students at the university, we were able to do a detailed study of the Student Teacher Centre (STC) building (see photographs 6 and 7), which currently houses the Visual Arts Department. The on-site process of close survey and documentation was verified by the archives found on archnet.org and created by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Several historic documents, drawings and photographs related to the buildings of KU are available on the website. Ecochard had generously donated all his documents and drawings to the Aga Khan Foundation in the 1980s.

In the archives, a document titled “Proposed Plan of the University of Karachi,” dated December 16, 1955, written by Ecochard, explains in detail the local climate and his plans for the campus. Faced with the design challenge of Karachi’s hot weather, Ecochard prioritised the design of his buildings for the end-user’s thermal comfort. His strategy was to capitalise on Karachi’s biggest natural resource: the south-west sea breeze, which blows regularly at an average direction of 245 degrees (west-south-west). The prevailing winds were the ‘composition axis’ on which the entire campus master plan was developed. The orientation of building facades plays a crucial role in this scenario. Ecochard places the long facades of the building perpendicular to the wind direction, opening all the rooms to the south-west sea breeze. In addition, Ecochard introduces vertical and horizontal sun shade devices all along the sun-facing facades, known as “sun-breakers” or “brise soleil.” The sun-breakers, which were built four to six feet deep, shade the building during the hot weather and cool the interior spaces (see photographs 8 and 9).

A document titled “Proposed Plan of the University of Karachi,” dated December 16, 1955, written by Ecochard, explains in detail the local climate and his plans for the campus. Faced with the design challenge of Karachi’s hot weather, Ecochard prioritised the design of his buildings for the end-user’s thermal comfort. His strategy was to capitalise on Karachi’s biggest natural resource: the south-west sea breeze, which blows regularly at an average direction of 245 degrees (west-south-west).

It is the combination of these two principles, facades perpendicular to the wind direction (passive wind design) and the sun-breakers that are shading the interior spaces (passive solar design), which greatly cools the indoor temperature. Another design element commonly used by Ecochard is the clearstory window, a passive design strategy that lets the hot air escape from the inside. It is remarkable that such simple design solutions can be employed throughout the buildings, completely transforming the interior climate. In Ecochard’s own words, “The comfort and favourable working conditions of the campus residents require protection against the unpleasant tropical climate. This protection will lead to a systematic orientation of the buildings facing the wind, and to a rational protection against the sun rays.”

In between the buildings, Ecochard planned gardens and vegetation with the intent of creating an oasis in the hot weather. Hence, Ecochard proposed innovative solutions intended to create a micro-climate within the university campus.

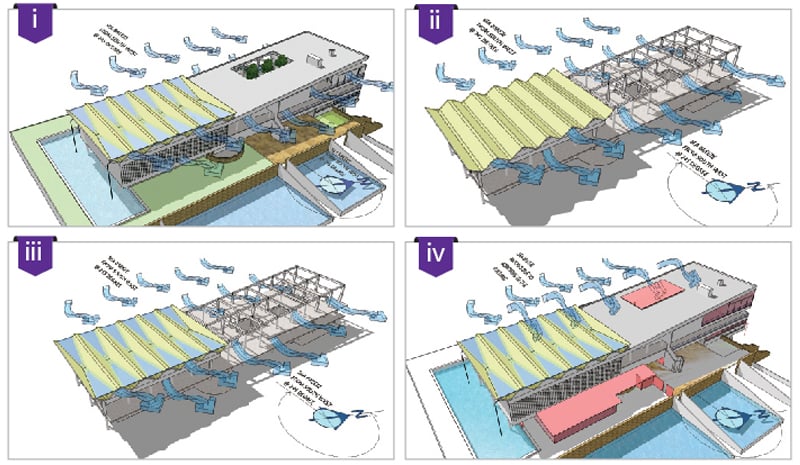

On a micro scale, as was analysed with the case study of the STC building, the original design was developed with impeccable execution. After the site survey and the study of the historical documents, we generated a computerised 3D model of the STC building and documented the existing walls, roof and floors, as well as recreated the original design intent of the building (see sketch i, below). The 3D model revealed a double roof structure over the main hall. The concrete folded plate structure was designed to span the tall space and the overlapping sloping roof was designed to catch the south-west sea breeze (see sketches ii and iii). The sun-breakers in the STC building shade the south-west and north-east façade (see photograph 10).

During the documentation of the STC building, we discovered that several rooms were added to the original building. Over the years, as the building use changed, rooms were added and the overall massing (general shape and form) of the building changed, a process known as ‘adaptive re-use’ (see sketch iv that shows rooms added in pink colour). Although additional space was needed for the growing University, these additions also heated the interior of the building by blocking the cross-air-ventilation, which was the main design intent by Ecochard. In our opinion, existing rooms should be modified or removed to allow for cross-air-ventilation, as intended. Adaptive re-use poses a great challenge for an architect to not only re-design an existing space for a purpose other than which it was built, but to also complement the original design of the building.

In Ecochard’s own words, “The comfort and favourable working conditions of the campus residents require protection against the unpleasant tropical climate. This protection will lead to a systematic orientation of the buildings facing the wind, and to a rational protection against the sun rays.”

Our friend Dr Moiz Khan talked enthusiastically about the design of the original KU campus buildings, as we toured the campus on his motorbike: “Our classrooms don’t need air conditioners or light bulbs during the day. The best part is the acoustics: even with 100 students, I don’t have to shout. My students can hear me clearly.” It was at that point that we decided that we needed to document and preserve these buildings.

Those of us who have studied, worked at or even visited KU cannot miss out on Michael Ecochard’s signature architectural style. These buildings are living monuments to Karachi’s evolution and a link to a vibrant student life since the 1950s. This alma mater is also a matter of regard, and a bond to a cross-section of the society across Pakistan and abroad.

During our survey, the most important lesson learnt was that documentation is actually a first step towards preservation. As noted by urban planner Arif Hasan, “His [Ecochard’s] buildings have been declared heritage monuments by the Heritage Committee of the Sindh Cultural Department under the Sindh Conservation (Preservation) Act 1994,” but preservation of a building is a several-step process. We have reached the initial stages only: documentation, an in-depth analysis and learning about the master architect’s original design intent. The next step can be the exploration of adaptive re-use or documenting the remainder of the buildings designed by Michael Ecochard.

Shabbir Kazmi of the American Institute of Architects is a practicing licensed architect who has been conducting independent research on Michael Ecochard’s work at Karachi University

Mariam Karrar is an architect and an educator and has been part of the faculty at the NED University Department of Architecture and Planning

Published in Dawn, EOS, November 26th, 2017

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.