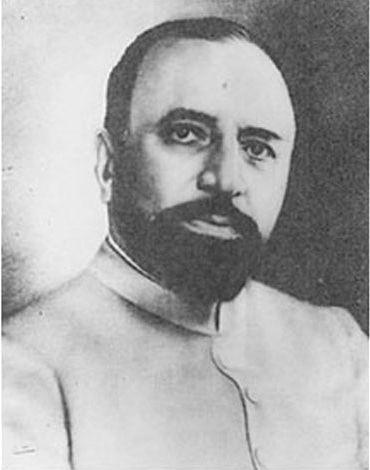

A LOOK at Haji Sir Abdullah Haroon’s volume of correspondence is enough to give us a fair idea of his place among the front-line workers of the Pakistan Movement. The correspondence can form a book on its own. The letters were often lengthy, had the force of logic, were couched in the political idiom of the day and were written in excellent English. This needs to be highlighted to show the transformation into a mature parliamentarian of an eight-year-old selling haberdashery.

A letter addressed, for instance, to Sir Percy James Grigg, a member of the finance ministry at New Delhi, consisted of 3,000 words and dealt mostly with Sindh’s finances. Other letters, written to the All-India Muslim League (AIML) and Congress leaders, besides politicians, religious personalities and scholars at home and abroad, including quite often the Aga Khan, dwelt at length on the political tangle in India as war raged, independence neared and the Muslims seemed to lack unity.

His career as a parliamentarian spanned decades. He was elected to the Bombay Legislative Council in 1923 and to the Central Legislative Assembly at New Delhi in 1926 and remained its member till his death on April 27, 1942. That he was chairman of the All-India Khilafat Committee and a member of the AIML Working Committee, which drafted the Pakistan Resolution, shows his stature as a politician. The Quaid-i-Azam noted his negotiating skills and made him head several key committees. This included a panel dealing with the now-forgotten controversy surrounding Manzilgah, which was a river-front mosque in Sukkur, built during the Mughal times but used as a military office during the Raj. Thanks to Abdullah Haroon’s negotiating skills the controversy was settled in Muslims’ favour.

Ignoring other committees which Haroon headed, let us note the Foreign Office which the AIML high command set up to convey the Muslim point of view to the world. The need for informing governments, lawmakers and the media abroad, especially the Middle Eastern peoples and the English-speaking world about the Muslim point of view on India’s complex political situation, was felt because it was going by default. Articles and letters to the editor were appearing in America by Congress hirelings, painting the AIML leaders as reactionaries who in complicity with the British were trying to sabotage India’s freedom struggle.

A Muslim American of South Asian origin sent to the AIML high command press clippings of propaganda stuff published in American newspapers, including one in the New York Times in its issue of Nov 15, 1940. The propaganda spewed venom against those leading the Pakistan Movement. Written by one Mr John Haynes Homes, a leader of the pompously named American League for India’s Freedom, it said: “Like the Princess, the [Muslim] League represents the reactionary vested interests, natural bedfellows of Imperialism, and not the Muslim masses.”

The articles and letters published in the British and American press couldn’t hide the source of propaganda because of the similarity of arguments. The same ignorance prevailed in the Middle East. Realising the gravity of the situation, the AIML high command chose Haroon to take up the challenge and inform the world about the Muslim point of view and the legitimacy of the demand for Pakistan

Haroon plunged into the job, the AIML foreign office got working in all earnest, and cyclostyled copies of news items highlighting the Muslim point of view and the case for Pakistan were sent to newspapers in Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Turkey, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and the Arabian peninsula. Besides, offices were opened in many Middle Eastern cities, including Basra, Baghdad and Damascus. In Britain among those who understood the Muslim point of view were Sir Louis Stuart and Sir Michael O’Dwyer. No wonder The Times, London, occasionally published the AIML point of view

His passion for Pakistan and the torment he suffered over the persecution of the Muslim minority in the provinces ruled by the Congress were evident in a letter he wrote to the Aga Khan, quoting Jinnah as saying “the Muslims of India have made a grim resolve that if they would go down they would go down fighting”, and even though Kashmir as a dispute was still in the future, Haroon said in a speech to a meeting of the Muslim Students of Punjab at Lahore on Feb 16, 1941, that they should take “a vow that you should not be clerks in the offices, or builders of new villas in the valley of Kashmir, but soldiers of Islam who are to live, struggle and die for their people”.

Truly did Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan’s first prime minister, say of Sir Abdullah Haroon that he was a “remarkable personality”, for he “combined phenomenal success in trade and commerce with selfless political service to his province and his nation”.

The writer is Dawn’s external ombudsman and an author.

Published in Dawn, April 27th, 2021