It’s likely that you’ve got some of Bilal Saeed’s songs on your playlist. It’s likely because there are so many: the lilting romantic numbers, the bhangra-pop songs perfect for dholkis, the Punjabi rap meant to blare loudly from cars’ stereo systems.

For nine years now, his music has skyrocketed on YouTube charts. But a lot of people who listen to Bilal’s songs assume that they have been sung by an international artist. His sound definitely does have a global appeal to it but this is also because, in all these many years, while he’s been raking in millions of views on YouTube, Bilal Saeed has continued to keep a relatively low profile.

“I realise this now,” he admits to me. “People have always loved my songs. Every single of mine has raked in over 50 million views on YouTube. But I always thought that my work would speak for itself and that I wouldn’t need to promote it. I’m a bit anti-social and I don’t have any ties with the media. If you look at my repertoire, my work is extensive compared to my peers!”

Bilal ponders at this point, “Then again, perhaps it’s better to be underrated rather than overrated!” he quips.

Bilal Saeed is the wildly popular singer whose name doesn’t strike a chord with most. His songs rake in millions of views on YouTube, yet he’s not the poster-boy for any corporate brand or won any awards in Pakistan. How does he feel about being so low-profile?

Changing the game

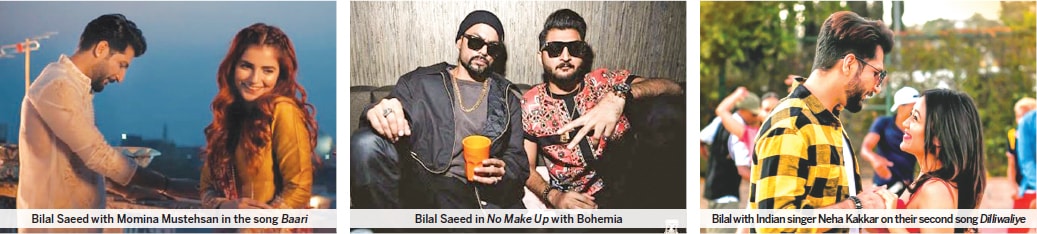

But while Bilal may yet not be the flavour of the month, or the poster-boy for a major soft drink brand, people in the music business know him very well. He’s worked with international labels and one of his songs has been featured in a Karan Johar production in Bollywood as well. And he has collaborated frequently with international artists; Indian singer Neha Kakkar, the Punjabi pop rapper from America, Bohemia, British-born Indian music composer Dr Zeus and Canadian Punjabi rapper Roach Killa.

He’s also travelled the world on extensive concert tours. Bilal tells me that right before the coronavirus pandemic struck Pakistan, he had been on the verge of coming on board a major Pakistani musical platform.

“Let’s see what happens once this pandemic is over, but even now I’m doing a lot,” he tells me. “I write, compose and produce my own music, and I have my own record label. There are about a 100 complete songs saved in my computer right now and I could just release them one by one, or as an album. I just performed in a live virtual concert sponsored by a cellphone brand and my new video, featuring Sabeeka Imam, released a few days ago.”

Which major platform was he planning to work with before the coronavirus broke loose, I ask. “Leave it. What’s the point of talking about it now?” Bilal says. “But I think my song Baari with Momina Mustehsan got so popular that a lot of new avenues immediately opened up for me. She has a niche audience while I’m more mass, and the melding of our particular styles went viral. For 35 days following its release, Baari was trending on YouTube. There were 1.5 million views daily! The song has been a game-changer for me.” Baari has racked up over 69 million views in just over six months of release.

He thinks back to another single that changed his life: his first song Baara Saal, which set his career in motion. “I had been a struggling musician at the time and I just released the song on YouTube and it became popular,” recalls Bilal. “Within two months, I had entered into a contract with a UK-based record label who signed me on with an Indian company. The song was then released again.”

Wasn’t the song Khair Mangdi also a game-changer, considering that it was featured in the Karan Johar mega-starrer Baar Baar Dekho? “Not really,” he reveals. “I have never been too focused on Bollywood, although I have a very big fan-following in Indian Punjab. All my songs that have released in India have been through different record labels. Khair Mangdi had been part of my album Twelve, which was released in 2012 and, one day, I had just randomly created a slow version of it and released it on YouTube. Five years later, I was told that Karan Johar wanted to include it in his movie’s soundtrack!”

I have never been too focused on Bollywood, although I have a very big fan-following in Indian Punjab. All my songs that have released in India have been through different record labels.”

He continues, “I believe that it was just destiny. I had been in Karachi for a concert and my band members and I were discussing how Bollywood never picked up my songs. I was telling them that if it was meant to be, it would happen and, at that very moment, I got a call from an Indian number. A man on the phone told me that they wanted to use my song in a movie and asked me how much money I would take for it. I thought that it was a joke and told him to call me later. It was only when he called me again that I realised that he meant business.”

The politics of music

Despite having won so much critical acclaim, does he ever feel disillusioned when he doesn’t get enough attention in his own country? He is yet to win a local award or be part of a major corporate endorsement. “I don’t want to sound clichéd but I’m being honest when I say that the biggest award for an artist is when people buy tickets for his concert and scream out his name when they see him. I have fans abroad who wait in line to see me perform live, and it makes me feel so blessed.

“Nevertheless, appreciation does matter. I have won awards in England and India, and I’ve been nominated at the Lux Style Awards (LSAs). I am yet to win a local award but it is no secret that, in Pakistan, winners are announced on the basis of personal preferences. If Ayesha Omar could go on to win an LSA for ‘Best Album’, for an album that no one had heard, then there’s really no credibility to our local awards.

“Similarly, corporate platforms such as Coke Studio have often very visibly promoted their favourites. You only have to read the audience’s comments underneath Coke Studio songs to realise which songs are truly hits and which ones are simply declared to be popular. It’s so sad, because these forums could have done so much to help new artists and to highlight their talent. Instead, they chose to partake in politics.

I have made up my mind that I’m not doing anyone any favours by singing and entertaining people. I’m doing it because I love it. And I have to plan my life so that my career remains viable.”

“I remember when Ali Hamza became the producer for Coke Studio, suddenly he stopped talking to people on the phone. People don’t realise in their arrogance that, when they are given a position of power, they should utilise it well.

“What helps is that my craft keeps me very happy. It’s ultimately all I really care about. I’m here for the long run and these short-term goals may make me happy, but I’m not obsessed with them.”

Money talks

Still, these short-term goals can be very lucrative for artists, which is why present-day musicians place such importance on corporate sponsors. Bilal needs to combine his love for craft with a head for business in order to reap long-term profits. “Yes, I know this, and artists aren’t always great at business,” he says. “I have learnt a lot through trial and error. There was a time when I would spend more than I earned on shopping! Now I realise the importance of making investments for the future. And I’m working with sponsors.

“When Amanullah sahib passed away in dire straits recently, it really made me think about where I was headed. A lot of older artists complain to the government that they have entertained audiences all their lives but now they are struggling with poverty. But I have made up my mind that I’m not doing anyone any favours by singing and entertaining people. I’m doing it because I love it. And I have to plan my life so that my career remains viable. This is why I launched my record label. It isn’t just to release my own songs but also for other artists. I’m also constantly performing in concerts. That’s the main source of revenue for any musician the world over.”

Bilal is also creating songs for a number of movies and web-series, including actor Adnan Siddiqui’s cinematic debut as a producer Dum Mastam. “There are a lot of plans in motion and once the Covid-19 pandemic has subsided, I will be following through with them.”

The onus lies on the pandemic coming to an end. But Bilal is accustomed to moving on despite setbacks. He recounts, “During the initial years of my career, I was contacted by Indian composer Honey Singh. He wanted me to write songs for him. We were planning on a collaboration but, ultimately, it didn’t happen. He was very supportive of me, though, and told me that he had started out the same way I did.

“Next, I decided that I wanted to work with David Zennie, who directed Honey Singh’s videos. I approached David and he quoted a very high sum for directing my video. I didn’t have that much money at the time but then, a year later, I approached him again. He went on to direct three of my videos. I have learnt that things may take time but I have to stay focused on my goals, and I will achieve them ultimately.”

He has other anecdotes to share. “I realised earlier on in my career that I needed to believe in my capabilities and not let others bring me down. There were so many people that I looked up to but, when I finally met them, I realised that their capabilities were limited and that they were users. Back in the day, I was working with the band Jal as a sound recordist. Farhan Saeed and Gohar Mumtaz had set up a studio and, while working there, I realised how overrated they were. They couldn’t even create their own content and they were unwilling to help others.”

Being overrated, at least, is something Bilal doesn’t need to worry about. “No, I am too committed to my craft to really bother with these concerns,” he agrees. “Most of the time, I’m just lost in my own world, composing something new, bringing a new idea to life.”

And he has a flair for zoning in on the right ideas: songs that are immediately catchy, that remind you of Punjab in the springtime, that are distinctive in merging electronica with bhangra beats. His songs are hits and his tunes are instantly recognisable. Bilal Saeed is the real deal. He doesn’t need to be a generic poster-boy to prove his mettle.

Published in Dawn, ICON, June 14th, 2020