BERLIN: Europe’s appetite for cheaper electricity is reviving mines that produce the dirtiest type of coal, threatening to boost pollution and raze villages that have survived since medieval times.

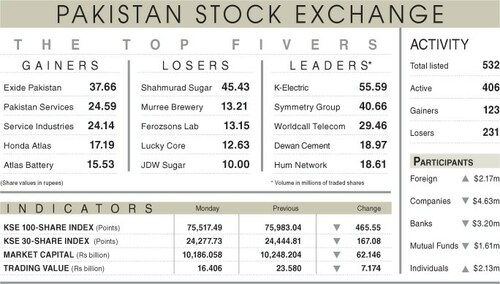

Across the continent’s mining belt, from Germany to Poland and the Czech Republic, utilities such as Vattenfall, CEZ and PGE are expanding open-pit mines that produce lignite. The moist, brown form of the fossil fuel packs less energy and more carbon than more frequently burned hard coal.

The projects go against the grain of European Union rules limiting emissions and pushing cleaner energy. Alarmed at power prices about double US levels, policy makers are allowing the expansion of coal mines that were scaled back in the past two decades, stirring a backlash in the targeted communities.

“It’s absurd,” said Petra Roesch, mayor of Proschim, a 700-year-old village southeast of Berlin that would be uprooted by Vattenfall’s mine expansion. “Germany wants to transition toward renewable energy, and we’re being deprived of our land.”

Lignite demand worldwide is forecast to rise as much as 5.4 per cent by 2020, according to the International Energy Agency.

Mining machines the size of skyscrapers stand just to the north of Proschim ready to swallow up the town of 330 residents near the German border with Poland. Vattenfall, which is owned by the Swedish government, is seeking approval to knock down buildings in the town to expand its Welzow-Sued lignite mine.

In Poland, PGE, which is the nation’s largest power producer, is upgrading a lignite-burning unit at its Turow plant. In the Czech Republic, a plan to relax mining limits may annihilate Horni Jiretin, a 750-year-old village that survived everything from plagues in the middle ages to the last two world wars.

Lignite’s revival is concentrating attention on the drawbacks of the fossil fuel and may actually bolster support for renewables such as wind and solar power, according to Barry O’Flynn, a director in the environmental finance and clean technology team at Ernst & Young LLP.

Lignite use fell 40pc from 1990 to 2010 as governments across the former Soviet bloc nations closed aging industrial plants.

Now, Poland, which gets almost 90pc of its electricity from coal, is stepping up use of the fuel as a way of ensuring energy security and maintaining employment in some of the nation’s poorest regions.

Lignite power production rose 3.7pc last year in Poland, while output from hard coal plants fell 7pc, according to PGE, the state utility.

In late 2011, it started a 858-megawatt unit at its Belchatow plant, Europe’s largest thermal power generation facility. The company’s strategy from 2012 assumed long-term reliance on lignite due to its low costs and the prospect of building new mines.

In the Czech Republic, Severni Energeticka AS is seeking to expand its mine past limits imposed in 1991, two years after the collapse of communism.

CEZ, the largest Czech producer of electricity controlled by the state, generates 48pc of its power in coal-fired plants. Its lignite mining unit, active in the same region as the army mine, plans to increase production 6pc to 24.1 million tonnes this year, the company said on Nov. 12.

In Germany’s Lausitz region, lignite mining has eliminated 136 villages since 1924, according to the Archiv Verschwundener Orte, a museum in Forst that chronicles the impacts of mining.

Expanding the mine at Proschim would unlock 204 million tonnes more of lignite for Vattenfall, which digs up about 60m tonnes a year.

Olaf Koall, a Vattenfall employee who lives with his wife and two children in Bohsdorf near Cottbus, says Germany needs more coal even as it expands renewables.

In Proschim, a red-brick town rebuilt after a fifth of its homes were destroyed in World War II, Hannelore and Klaus Jurischka live in a farmhouse rebuilt after it burned to the ground in 1945. It now has solar panels on the roof, part of the town’s effort to foster renewable energy. Proschim’s photovoltaics, wind and biomass plants produce enough power for about 5,000 homes.

“I’m not leaving,” said Hannelore Jurischka, standing in the inner courtyard of her home, decorated with a large cherry laurel bush and two blue-hatted garden gnomes. “This is my home. No amount of money can compensate me for that.”

By arrangement with the Washington Post/Bloomberg News Service

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.