TWO historical sites in China recently made it into the Unesco World Heritage list, bringing the number of such sites in the country to 50.

China looks set to claim the title as the world leader as soon as it has 54 other sites on a tentative list while top-placed Italy has 40 pending. Italy currently has 51 Unesco World Heritage sites.

But while having its sites recognised by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) is a matter of pride for many in China, it has also been a source of concern in recent years.

Tourists are worried as previous Chinese heritage sites that entered the Unesco list would often experience a deluge of visitors and charge higher admission prices soon after.

For instance, the Classical Gardens of Suzhou raised group admission prices to 376 yuan ($55) by 2004, up from 98 yuan in 1997 when it entered the Unesco list.

These price hikes peeve Chinese tourists as admission prices at China’s Unesco world heritage sites are already comparatively higher than those overseas.

The cheapest ticket sold at the Zhangjiajie natural reserve in central Hunan province costs 245 yuan and is valid for three days.

Yellowstone national park in the United States charges $12, or about 74 yuan, for a seven-day ticket.

A key reason is that many local governments spent huge sums of money in applying for the Unesco status and need to recoup their outlay through tourist dollars.

Out of the 1.2 billion yuan spent by seven cities and counties in central China to get the Danxia Landform onto the Unesco list in 2010, 450 million yuan was borne by Xinning county in Hunan province. It was more than double the local county government’s annual income of 200m yuan.

Another concern is that, many officials, despite pledging to focus on heritage conservation, often neglect this once their sites make it to the list.

As a result, many of China’s Unesco heritage sites are subject to poor planning and over-commercialisation, triggering warnings for some from Unesco.

Within six years after it was placed on the Unesco list in 1992, the Wulingyuan Heritage District in Hunan added some 400 hotels and restaurants plus several hundred shops and service facilities within a 39 square kilometres area of the valley.

Thus heritage experts have pointed out that earning a Unesco badge of honour could be more detrimental than beneficial to a new heritage site.

At its 40th meeting in Turkey on July 17 where the Unesco World Heritage Committee decided to add Shennongjia to the list for natural sites, the panel cited concerns over tourism pressure at the site. A new airport was built in 2014 to cater to China’s domestic travel boom.

Li Faping, mayor of the Shennongjia forests district, reportedly had to pledge better conservation efforts in a bid to allay the committee’s concerns and secure the Unesco status.

Such concerns were absent in the initial years after China ratified the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage in 1985.

According to heritage expert Chen Shen in a 2010 paper, the World Heritage status seemed to be more an honour than an economic opportunity for the nation then.

The change began around 1997 after the Unesco listing of the ancient Pingyao and Lijiang towns in northern Shanxi and Yunnan provinces, respectively, sparked growth in the local economy.

Tourist arrivals in Pingyao increased by 300 per cent in 1998. By 2000, the county government had tripled its annual revenue.

As a result, World Heritage sites in China became intertwined with dollars and cents, with applications to the Unesco list driven more by local governments than preservation experts, he added.

The situation improved after 2001 when Unesco set a new rule that each country could get only one site onto the list each year, which killed the fad in China. The rule was relaxed in 2004 to one natural site and one cultural site from each country.

To be fair, things also improved with greater media scrutiny on poorly managed sites. Local governments also became more aware of the need to mitigate the impact of tourism.

Central Hubei province’s Shennongjia natural reserve, this year’s winner, will cap the number of annual visitors at 798,000 annually — 14pc more than last year.

“The quota was set based on a comprehensive analysis of the environment and the capacity of our tourism infrastructure,” Ai Weiying, deputy head of the Shennongjia Forestry District government, told China Daily in a report last Thursday.

He said more eco-friendly shuttle buses would be introduced at the site to manage the expected influx of tourists, who will be allowed to follow only planned itineraries within the zone.

The Guangxi cultural heritage agency is mulling viewing platforms to prevent tourists from touching the Zuojiang Huashan Rock Art.

Also, there are positive examples of Unesco heritage sites being managed in a sustainable way that also help boost the local economy. Zheng Lijun, 53, who runs a youth hostel in southern Fujian province’s Wuyi Mountain, which was listed as a World Heritage site in 1999, said the local government has to adhere to high standards to avoid being struck off the prestigious list.

“This means management at World Heritage sites tends to be better than elsewhere,” he told The Straits Times.

Still, heritage experts say more can be done.

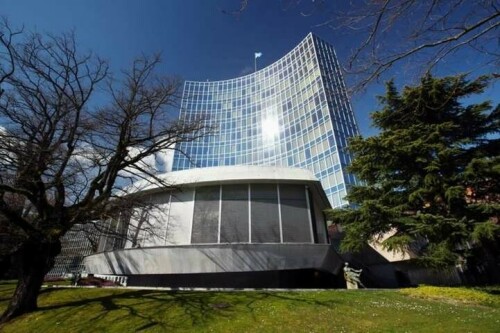

Professor He Yun’ao, director of Nanjing University’s Institute of Culture and Natural Heritage, proposes enacting a dedicated law on the protection of World Heritage sites, citing as an example Italy’s law on protection of World Heritage sites.

“As China looks set to become the world leader in World Heritage sites, a dedicated law may be needed to ensure that local governments do not exploit the sites,” Prof He, who has taken part in several of China’s Unesco bids, said.

— The Straits Times/Beijing

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.