Years later, when the opponents of PPP assembled again, this time to form Islami Jamhoori Ittehad (IJI), for their election symbol, they went with the bicycle, which stood for the humble lower middle class which has achieved little and is yearning for a lot more. IJI had multiple identities, probably as many as its component parties but two elections down the road one party synthesised the ‘usable’ characteristics of all members into a new distinct identity. We know it as PML-N and it chose the tiger to symbolise it in the elections. The decision, I am sure, was not inspired by the party’s remarkable feat of devouring the vote banks of the rest of the partners in the alliance. During that period, fast-growing Eastern economies of Singapore, Thailand, South Korea and Malaysia, called Asian tigers, were aspired to as the success models by many developing countries. So in PML-N, another cub was born to Asia somewhere around Lahore but before it could learn to roar it was hit by hiccups.

In 1993, PML-N polled an impressive eight million votes – more than what PPP had polled but they did not translate into enough seats to help the party form a government. In next elections in 1997, PPP was in complete disarray and almost half of its ardent supporters stayed away from elections or switched sides. PML-N vote bank swelled to 8.75 million. The gain by PML-N and more importantly the loss suffered by its main rival, PPP, together gave the party an unprecedented majority in the elected houses. Roar, it did and was heard clearly by the higher courts and even by the GHQ. Unfortunately, however, less than half of the party’s voters, 3.4 million to be exact, proved to be die-hard as that is what the party polled in the hard times of 2002. As the curtains dropped on the king’s party in 2008, PML-N won back many of its supporters and doubled its vote to 6.8 million though it still fell short of its glory-day figure. So the PML-N had a roller-coaster ride: exciting and not something that lion-hearts should be afraid of. The actual dilemma that our tiger faces, however, is something else.

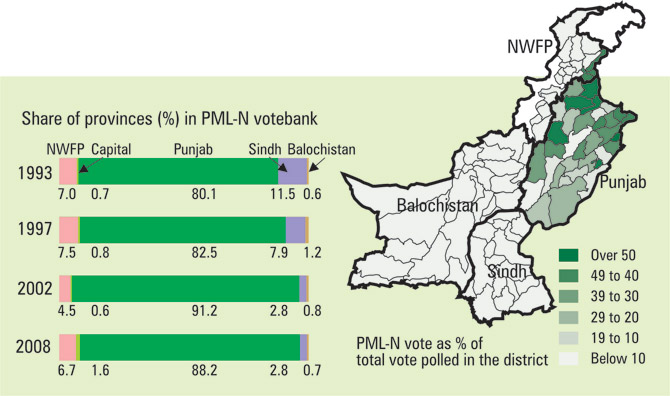

Consider these facts. 88 per cent of the PML-N’s vote in 2008 came from Punjab. It had always been in 80-to-90 per cent range. Every tenth PML-N voter (of 2008) hailed from Lahore. The party’s vote in three urban districts of Lahore, Faisalabad and Rawalpindi was a quarter of its vote bank. Two third of the party’s vote (68.1 per cent) came from 15 districts of central and northern Punjab. PML-N practically does not exist outside Punjab except for the three Hindko-speaking districts of Pakhtunkhwa. Outside of this region, which means almost half of the national seats PML-N bagged only 2.7 percent of the votes polled in 2008. So PML-N is a Punjabi party dominated by its urban entrepreneurial class. But what’s wrong with that? Nothing, except that the party itself refuses to accept this simple fact. It wants to represent the entire nation and rule over the entire country.

Regular elections do not augur well for the so-called national parties in countries with as diverse populations as in India and Pakistan. That’s a lesson from our recent electoral history. The example of Indian National Congress is a classic one. The party single-handedly ruled over the largest democracy of the world for decades but now it only survives as a façade to an inherently weak and always struggling alliance of regional parties and competing political interests. Even the recent “youth tsunami” led by Rahul Gandhi has not been able to turn the tide despite much speculation.

Political parties these days operate more like collective bargaining agents of certain interest groups and there are innumerable groups competing for a share in political power. A multitude of cultural identities, diverse ethnic profiles and contrasting class characters intertwine with highly uneven patterns of economic development to generate a galaxy of interest groups. It is ‘humanly’ not possible for any one party to cut across this mind boggling diversity and work out a common denominator.

While accommodating this assortment of interests, political parties are handicapped by a lack of intra-party democratic structures and culture. If and when one interest group is not satisfied with its representation within the party, it is bound to splinter and form a new party, win some seats or clout through elections and come to the negotiating table to bargain with the ‘parent’ national party or break a pragmatic deal with others like itself. So the electoral politics which seems to be helping this process of differentiation is also instrumental in channelising it back into mainstream political discourse. Electoral politics thus saves the day and stops this process of Balkanisation of the national parties from leading the discourse into a much feared anarchy.

PML-N is representative of one group: the entrepreneurial class of central Punjab, which is ahead of all others in the country by a great margin and is seen as their main competitor, if not as the major adversary. PML-N cannot simultaneously act as the power broker (or as the political representative) of its core Punjabi supporters, as well as that of their weaker competitors. Its national rhetoric, thus, is seen as an attempt by the leading competitor to maintain its top position and stifle competition. A tiger may be awesome and impressive but that doesn’t mean others can trust him with their lives.

Tigers, anyway, are fiercely territorial by nature and for them to suppress their nature cannot be advisable. PML-N must focus on representing the people it does the best, and not waste too much energy of nationalistic jingoism. Or else, when the time comes to roar at the top of its voice, the tiger might find itself embarrassingly out of breath.

The writer works with Punjab Lok Sujag, a research and advocacy group that has a primary interest in understanding governance and democracy.

The views expressed by this blogger and in the following reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Dawn Media Group.