Pakistan has a rich and diverse legacy of visual art and design culture that is widely recognised across the globe. This not only includes fine art but also textiles, architecture, calligraphy, and various forms of craftsmanship such as tile-work, woodwork, ceramics, weaving etc.

Such traditional practices are known for their elegant carvings, unique inlay work, decorative floral patterns and meticulous geometrical tessellations. Having been on the verge of extinction, these once-forgotten forms of crafts are now being revived and promoted after a recent proclivity towards adopting sustainable practices and for revisiting our cultural roots.

While most of these crafts have now regained visibility, one form of visual art practice remains hidden and is yet to be acknowledged as a traditional art genre in itself. Likhai or draughtsmanship/delineation is a practice that interestingly ties all forms of indigenous art and craft-making. It establishes itself as their common foundation.

This technique employs the use of mathematics, geometry, symmetry, proportions and harmony — each of which denotes a deeper, philosophical meaning.

Renowned educator, author, artist and one of the senior-most architects of Pakistan, Kamil Khan Mumtaz brings this form of drawing to the forefront in his solo exhibition, Likhai held at the Koel Gallery in Karachi.

Eminent architect Kamil Khan Mumtaz shines a light on the often-ignored craft of draughtsmanship through his drawings

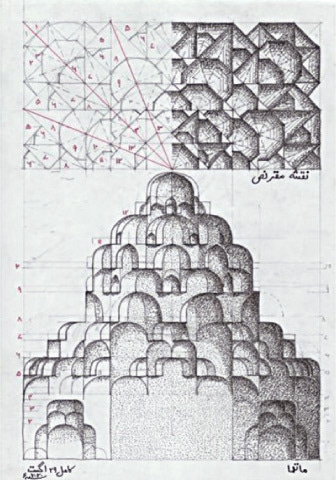

He showcases architectural drawings that he rendered with pen and pencil. The monochromatic works survey his recent and past personal projects, interior spaces and facades of religio-cultural monuments, and the majestic latticework that is commonly found in Islamic architecture.

The artist deliberately leaves his process of rendering half-finished, which consequently exposes the underlying geometry, or likhai that he had to initially construct.

For Mumtaz, the subject of the work is not so much the architectural front as it is the traditional delineation required to realise the image. This process has not only metaphorically faded into the background from one’s appreciation, but it also, quite literally, gets concealed out of view under the final image or product. The artist strips the layers from the perceivably finished image for the crucial form of art to resurface.

Mumtaz is a pioneer in the conservation of our architectural heritage and bags much to his credit in regards to promoting the traditional arts, including architecture. The artist dismisses modernist thinking and outlook on life that focuses on consumerism and commodification of art, knowledge and ideas. His opinion is reflected in his meticulously mapped drawings, which are instantly recognisable as deeply embedded in our local art and architectural practice.

The artist includes Urdu terminologies concerning architecture and construction in some of his drawings. These words may read foreign to most of the viewers and highlight the perils of a growing cultural disconnect. Out art education actively overlooks the indigenous paradigm of competency, skills and the vernacular language.

There is something intrinsically spiritual about the drawings which tap into the viewer’s viscera. Historically, the arrival of Islam has had a significant influence in shifting the ideology, techniques and visuals within the landscape of indigenous art and craft. It brought forth ideas about unity, a grounded centre and the infinite cosmos.

Mumtaz’s use of the grid, diagonals, repetition, symmetry — all of which are elementary foundations of repetitive geometric designs — is meant to connect the viewer to a higher state of consciousness. The drawings provide spiritual solace and pull the viewer in for a silent yet potent dialogue.

This exhibition also facilitates bringing and explaining architecture to a wider audience. Except for public buildings, architecture — unlike art — is rarely accessible to the public eye. However, one cannot deny that experiencing a two-dimensional drawing of an architectural space will never be the same as physically experiencing that space in its three dimensionalities.

Only after witnessing the passage of time, light and shadows, while navigating within the space, can one grasp the mood and the connate essence of the structure. Mumtaz comes in quite close in conveying the spirit of these structures by recreating that immersive experience. The mathematically determined proportions and scale, along with the precision and finesse in his line drawings that portray lights and shadows, manage to teleport the audience into those spaces.

Many traditional forms of arts in Pakistan are extensively researched and are still thriving through generational inheritance, the continuation of the ustad/shagird [teacher/student] system, and the survival of gharanas [musical lineages]. Draughtsmanship or likhai however, awaits to be recognised as another indigenous art, let alone be studied.

Mumtaz’s exhibition is an effort in that direction. The sublime drawings demand a mental and emotional presence. They awaken our spirituality, reconnect us to ourselves and realign our attention towards a neglected form of art that has been an enduring local tradition.

“Likhai” is being exhibited at the Koel Gallery in Karachi from April 27, 2021 to May 10, 2021

Published in Dawn, EOS, May 16th, 2021

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.