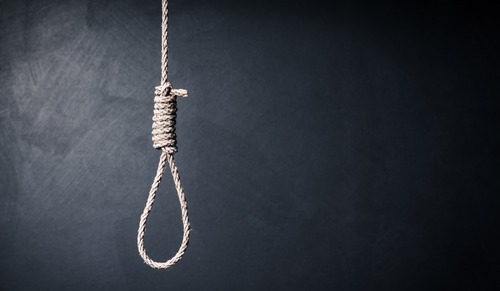

ON World Day Against the Death Penalty, the question once again arises: should the state — consisting of human beings, prone to human error — make decisions on who gets to live or die?

There are philosophical arguments in support for and against the death penalty and intrinsic to these are themes of social order, punishment and retribution.

But what about justice?

When emotions and paranoia run high, humans are less likely to be convinced by the lucidity of an argument. But justice has to remain impartial; it cannot be swayed by popular sentiment. And it cannot be rushed to cover up its systemic failings.

Pakistan is one of 57 countries that retains the death penalty law.

Since 2004, we have sentenced 4,500 people to death by hanging.

In 2008, a moratorium on the death penalty was imposed. No executions occurred between 2009 and 2013 (barring one in 2012).

But in the aftermath of the APS attack in 2014, when 132 schoolchildren and nine others were brutally murdered, the moratorium was lifted and military courts were propped up.

Few challenged the decision. The country was hurting. Blood had to be repaid in blood.

Since the lifting of the moratorium, Pakistan has carried out 465 executions.

True, the death penalty gives citizens living in chaotic times a superficial sense of security; it also satiates the darker aspects of human nature (revenge, scapegoating, and the element of ‘purifying’ society of ‘anti-social’ elements).

But it is also evident there can be no trial in which courts guarantee flawless prosecution or ensure complete absence of arbitrariness.

And it is the poor who are largely made victims of a faulty justice system.

Unable to cover legal fees, they are at the mercy of state-appointed lawyers. It is also common practice for investigative officers, on a tight budget, to write reports in favour of whoever pays them well. Mental illnesses are rarely factored in.

The vast majority of admissions of guilt are through confessions, which can be extracted through torture.

Despite all these faults and more than enough reasons for doubt, we continue to have on the statute books the highest form of punishment for 27 offences, ranging from (alleged) murder to (alleged) treason to (alleged) blasphemy.

Death is irreversible. Let’s not create more victims in the process of ‘justice’.

Perhaps both state and society should also reflect on the circumstances, and their own role, in creating criminals.

Published in Dawn, October 10th, 2018