WHILE continuity is the word to characterise much of Pakistan’s social and political life, a great deal has also changed over the years.

During the last decade or so a very profound transformation of the public sphere has been effected by the electronic media. The nature and extent of this transformation has yet to be properly investigated, both by media persons themselves and serious scholars.

If and when a meaningful study of this phenomenon is undertaken, it will, I think, be definitively established that a new elite has emerged in Pakistan, whose influence is growing by the day.

The media — owners as well as professional journalists — has always been an important social, economic and political player in Pakistan. Until Gen Ayub Khan’s 1958 coup d’état, many of the most influential newspapers in the country, including Pakistan Times, Imroze and Lail-o-Nahar, were actually run by leftists operating under the guise of Progressive Papers Limited (PPL).

After PPL was seized by Ayub’s stooges, a virtual state monopoly was established and almost all media outlets became clearing houses for state propaganda.

It was yet another military dictator who was in power when the TV media ‘revolution’ unfolded at the turn of the millennium. Gen Musharraf repeatedly claimed that he alone deserved credit for deregulation of the electronic media, but in truth the imperatives of capital had much more to do with the coming of 24-hour television into our lives.

There are many commentators who continue to hail cable TV as the ultimate accountability mechanism, the closest thing to a democratic leveller as exists in Pakistan.

On the other hand, a growing number of people have become increasingly sceptical about the manner in which TV anchors and producers manipulate public discourse, often reinforcing state ideology in an extremely retrogressive way.

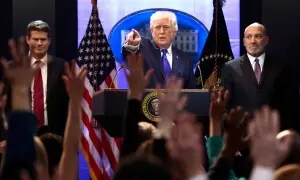

The media’s ability to chart public discourse is in itself not new. What stands out as remarkable is the power that TV ‘people’ have come to exercise over a very short period of time.

Indeed, it can be argued, as Akbar Zaidi has done on these very pages (April 9, 2012), that many anchors have arrogated to themselves the role of public intellectuals in an era where the very notion of the ‘public’ is as virtual as it is real.

This is despite the fact that there is an absolute dearth of genuine investigative reporting on TV. Even when one comes across so-called ‘human interest’ stories, social and political orthodoxies are rarely questioned and information sources inevitably prove to be self-selecting.

For the uncritical watcher of television, importance is attached then not to the issues that are raised by the storyteller but the fact that a particular storyteller is more compelling than any of the others. It is thus that a dozen or so TV anchors have very quickly become (urban) household names, and not necessarily because of journalistic prowess.

These dozen or so anchors — and the list will grow — have become bona fide Very Important Persons. They do not stand in queues or get subjected to security checks nor do their often serious transgressions necessarily result in meaningful loss of status, wealth or power (as was evident during and after the Malik Riaz exposés).

It is not by chance that this new media elite has come to the fore more or less at the same time that the Supreme Court has emerged as a relatively autonomous power centre in Pakistani politics. The media and judiciary were both major protagonists in the anti-Musharraf movement and therefore established their credentials as apparently untainted defenders of the ‘public interest’.

They are both popular with a burgeoning urban middle class that is thoroughly dismissive of formal politics. Perhaps most importantly, the media and judiciary can be carriers of state ideology in an era where it is no longer politically correct to call for the disruption of procedural democracy under the guise of the ‘greater national interest’.

This is not to suggest that the media (and judiciary) is incapable of being anything other than pro-establishment. As I noted above, many significant media outlets were bastions of anti-establishment ideas during the first decade after the inception of the state. Having said this it is highly unlikely that an entity like the PPL will once again emerge, especially given the role that big money now plays in the media industry.

Many progressives believe that the social media is a site of many radical potentialities. I agree that a plethora of virtual communities that can be created and sustained through the social media. There is, however, no guarantee either that these communities necessarily become strongholds of progressive ideas or that they help build meaningful political alternatives to status quo. Importantly, there is far less chance of a social media ‘elite’ emerging in the manner of the TV media elite. Because of the medium, social media users relate to one another on a much more equal footing than the TV viewer relates to the all-powerful anchor. Yet the social media can hardly be seen as a great leveller in a world in which the ‘digital divide’ is becoming more rather than less pronounced.

In the final analysis, we are currently witnessing the emergence of an elite like no other. While those who control the means to disseminate information in society have always exercised power, the technological changes that have taken place over the past decade or so, the ever-insatiable appetite of capital to reproduce itself, and the peculiar contradictions in Pakistan’s structure of power have given rise to an altogether new situation.

Notwithstanding its claims of false modesty, and its self-anointment as public watchdog par excellence, the new media elite is well aware of the extremely privileged position that it has come to occupy in contemporary Pakistan. It uses its privilege unabashedly and projects a holier-than-thou attitude as if to suggest that it bears no responsibility for the myriad problems that we encounter.

In fact, like all other elite segments, the media elite too is part of the problem rather than the solution. It constantly seeks to extend its power, both material and in terms of its perceived right to determine the public interest.

It does not tolerate fundamental questions about the ideological behemoth that is the Pakistani state, the various forms of oppression in Pakistan society, and the imperatives of global capitalism. And like any elite throughout history, its fall will be as precipitous as its rise.

The writer teaches at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad.