Despite slapping a ban on all political activity on March 29, 1978, General Ziaul Haq continued to contact politicians — he wanted to orchestrate a scenario that allowed him to retain all power. With many sycophants around him, Gen Zia began to believe that he was the best man to rule the country.

Rumours were rife about the formation of a self-styled national government. On Gen Zia’s insistence, Sardar Abdul Qayyum held a meeting with Gen Chishti on April 1, and later told journalists that a broad outline of such a government had been discussed. He expressed hope that the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA), some non-PNA parties and a few ‘moderate’ PPP leaders would join that government if it came into being. From the PPP, the names of Maulana Kausar Niazi and Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi were doing the rounds in almost all circles.

Maulana Niazi had even told journalists that he had met Mohammad Hanif Khan, Mir Afzal Khan and Nasrullah Khattak of the PPP’s “liberal group”, and that the group was opposed to confrontation. He had claimed that if the PPP proper did not join the proposed government, the liberal group would join and support it. Gen Zia himself confirmed the news on April 10, when he said that the formation of a national government was on the cards. On April 13, Gen Zia met Jamaat-i-Islami chief Maulana Maududi at his Lahore residence and discussed the issue of a national government.

With changes on the western border, General Zia ups efforts to give civilian legitimacy to his government

By that time, it had become evident that Gen Zia wanted to stay in power for as long as he could. To provide his government with a civilian facade, Zia wanted the support of some politicians, and to create consensus among splintered political leaders. Through the Election Cell, he had offered the PNA in March and asked them to join the proposed national government. The alliance had accepted the offer, albeit with certain conditions, but now, once again, the General wanted to evaluate them.

The Cell invited those PNA leaders who had met Gen Zia, Gen K.M. Arif, Gen Jamal, Gen Chishti, Gen Rao Farman Ali and Haji Maula Bakhsh Soomro on April 15. The PNA team included Mufti Mahmood, Mian Tufail Mohammad, Pir Pagara and Prof Ghafoor Ahmad. They had a prolonged discussion but could not come to a conclusion.

Later, the General also met Maulana Kausar Niazi, who had earlier expressed his willingness to cooperate with the military government. While Gen Zia continued to meet leaders and invite them to join the proposed national government, Asghar Khan, who had parted ways with the PNA, clearly said that restoration of civilian rights and holding political activities were the main conditions for his party’s inclusion in the so-called national government.

An unexplained situation prevailed. It was not clear why Bhutto’s main counsel Yahya Bakhtiar wanted to prolong the proceedings of the case from the very beginning. Most law experts believed that it was this delay that resulted in an unfortunate judgment in the case.

The developments on Pakistan’s western border were also causing tension in political circles. The change of leadership in Afghanistan on April 29 brought an end to Sardar Daud’s government; a new government led by Noor Mohammad Taraki had taken over. This was a crucial development: the socialist block led by the USSR had recognised the new Afghan government. On May 5, Pakistan also recognised Taraki’s government.

Meanwhile, Gen Zia’s meetings continued apace. On May 8, he met Baloch leader Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, who rejected the idea of a national government, saying that it could not replace a government formed after general elections. The other Baloch leaders were not available nor were they in the interior of Balochistan or Sindh, Zia was informed.

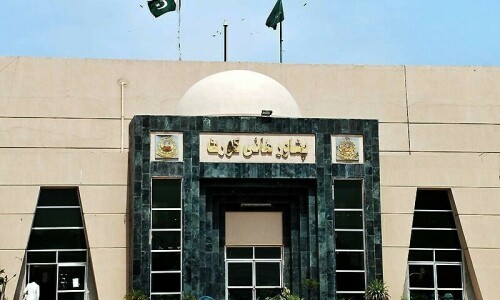

On May 20, the Supreme Court began hearing the appeals of Bhutto and four other accused. The nine-member bench took up Bhutto’s application in which he had demanded that Chief Justice Anwarul Haq should not sit on the appellate bench, and that he had no right to form the bench to hear his appeal. Bhutto’s lawyer, Yahya Bakhtiar, said that the case against his client was mala fide and instituted on political animosity. In reply, the federation’s counsel, Sharifuddin Pirzada, argued that Bhutto’s application had been moved with personal grudge and ill-intention.

Both requests were rejected, with the observation that no one had the right to ask for the formation of a particular bench, and that it was only the prerogative of the chief justice to nominate judges to hear an appeal.

Bhutto’s lawyer Yahya Bakhtiar wanted the court to allow Bhutto to be present in the court but the bench ruled out saying that three counsels were on record to plead Bhutto’s case, and they could meet the appellant and get instructions. The defence lawyers complained to the court that Bhutto had been ill for some time and had not eaten anything. The court instructed the prosecutor to submit a clarification in this regard. The clarification said that Bhutto was getting all facilities admissible under the law. He was also getting packed food from defence lawyers.

An unexplained situation prevailed. It was not clear why Bhutto’s main counsel Yahya Bakhtiar wanted to prolong the proceedings of the case from the very beginning. Most law experts believed that it was this delay that resulted in an unfortunate judgment in the case. Bakhtiar had earlier moved an application that since he could not prepare the case papers by May 6, the hearing may be delayed. The court replied that he had been involved in the case from the beginning and knew everything; therefore it was not difficult to prepare the case. Nonetheless, the court extended the hearing for two weeks and the hearing began on May 20.

On the other hand, while Benazir Bhutto was still under house arrest in Karachi, the military government ordered on May 22 that Begum Nusrat Bhutto be detained in her house in Lahore for three months. She was charged with meeting people without the permission of martial law authorities.

Next week: A province of unending miseries

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, September 28th, 2014