THIS could be — should be — Europe’s finest hour, the moment of decisive action to defuse mounting tensions between Russia and Ukraine, an excellent opportunity for the 28-nation European Union to prove its credentials as a peacemaker and regional superpower.

Those expecting the EU to take the lead in the Crimean crisis complain that Brussels should be tougher with Russia, more solicitous and generous with Ukraine and more pro-active in seeking a peaceful solution to the mess in Crimea.

The critics are right of course: Europe is once again divided, querulous and confused in the face of a major geopolitical challenge. But while Europe’s disjointed reaction may be disappointing — it should not surprise.

As European policymakers often underline, the EU is a strange beast, unlike any other major global player. Here are some reasons why:

First, the EU is still working on developing a common foreign policy and until it does so — if it ever does so — it will have no real global clout. Different capitals still want to keep the reins of foreign policy in their hands to defend national interests and pursue national priorities.

Second, no country or politician has yet come up with a formula for dealing with a resurgent and increasingly assertive Russia and Vladimir Putin, its prickly, nationalist leader.

The US is still struggling with the aftermath of a failed “reset” in its relations with Moscow. Germany, which has long persevered in developing close ties with Russia, now appears lost on how to deal with Moscow. China sees itself as a friend of Russia but has made clear that it does not believe in foreign interventions.

Third, the crisis highlights the foreign policy challenges facing the EU as it operates in an increasingly globalised world where its post-modern values and interests stand in contrast with the ambitions and plans of nation states.

While observers often lump the US and the EU together as the “West”, putting the two in the same basket is a mistake. Whether dealing with Russia, China or the Middle East, America’s strategic interests are very different from those of Europe.

It’s not just the fact that even in a multipolar world, the US remains the dominant power, with strong “hard” and “soft” attributes which together carry global clout. It’s that the EU’s “soft power” works in different ways compared to other countries, including the US.

When push comes to shove, America still ponders military intervention — even under President Barack Obama’s “no more wars” mantra. In the EU, France and Britain may still like to flex their military muscle, but the majority of Europe remains opposed to war as a solution to global problems.

Most strikingly, as the ongoing crisis has illustrated, Russia and Europe diverge on many counts. The talk in Europe is of partnerships, trade, aid and diplomacy. The focus is increasingly on a “comprehensive approach” to helping countries in trouble, with financial assistance going hand in hand with trade concessions.

This is of course a far cry from Russia’s increasingly strident nationalist course of action.

Europe wants a stable and prosperous ring of friends around it. The EU’s “neighbourhood policy” now under attack as not being up to the task, is meant to raise the level of prosperity and encourage democracy across Europe and in North Africa.

Russia’s dealing with its “near abroad” is one of master and slave, with all neighbours kept firmly in check and under its yolk.

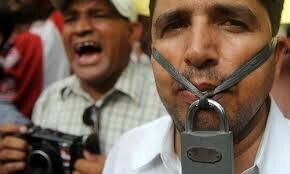

When the EU wants to punish countries for misconduct — human rights violations, breaches of international law, etc — it opts for sanctions, a freezing of financial assets and visa bans. As the crisis in Crimea has shown, Russia doesn’t just talk tough, it invades.

In addition, in a complicated world of economic interdependence where adversaries are also economically tied to each other, the EU firmly believes war is no longer an option. That is after all, the European experience.

The sentiment is apparently not shared by either Japan or China which are intertwined economically but continue to quarrel acrimoniously over small islands in the East China Sea.

Also, when it comes to EU relations with Russia, history matters. EU nations once under Soviet occupation, such as Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and the Czech Republic, are taking a tougher stance on Russia than Germany, Italy and others which have close economic ties with Moscow and depend on it for gas supplies.

Poland has warned that Russia is like a predator that gets hungrier as it eats, with the country’s Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski warning recently that European weakness now will result in another Russian intervention in other countries.

Warsaw is likely to issue the warning again when EU foreign ministers meet on March 17. The meeting is expected to agree on travel restrictions and asset freezes against Russians deemed responsible for violating the sovereignty of Ukraine. The measures are being coordinated with the US, Switzerland, Turkey, Japan and Canada, an effort to ensure the sanctions net is as tight and effective as possible.

Yes, Europe’s response to Russia, Ukraine and Crimea has been messy, slow and ponderous. But the EU is not alone in finding life difficult in the 21st Century.

—The writer is Dawn’s correspondent in Brussels.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.