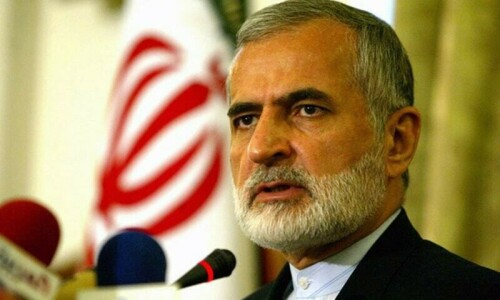

TEHRAN: For many of Iran’s poor, he is a modern day Robin Hood with an Islamic twist, a pauper against a prince: meet Mahmood Ahmadinejad, the man who could be Iran’s next president.

His critics have been trying to cast him as a political leper, a hardliner — even a fascist — bent on dragging the Islamic republic into the dark ages. A vote for moderate conservative cleric Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, they argue, is the only option.

But like it or not, Ahmadinejad has been building momentum among Iran’s frustrated underclass ahead of Friday’s run-off against Rafsanjani, capturing support from people ground down by unemployment, inflation and corruption.

“Ahmadinejad, he has been poor himself,” said one such supporter, Mohammad Beigi — who has a thankless job monitoring a taxi rank in smog-ridden downtown Tehran.

“The ones who say he was a terrorist should know that murders were carried out under Rafsanjani’s rule,” he says of the other candidate on offer, who has already served as Iran’s president from 1989 to 1997.

In Ahmadinejad, many of Iran’s impoverished classes see a man they can relate to — austere, unpretentious and God-fearing. On one occasion, the Mayor of Tehran even turned up wearing the orange overalls of a street sweeper.

The 49-year-old mayor — charged with managing the space of around 10 million people and a huge budget — also still drives a Paykan, Iran’s cheapest and dull people’s car.

His election film stirred up such an image with Elmer Bernstein’s rousing theme to “The Magnificent Seven”. This choice of tune may have been unintentional, but the message is there. Ahmadinejad will take from the rich and give to the poor.

“Rafsanjani is rich and has no idea about people’s suffering,” charged 35-year-old Amir Reza Behzadi, a taxi driver who also drives a Paykan. “What we need is a president who can control prices.”

The defeated reformist movement, and even Rafsanjani himself, have all scathingly attributed Ahmadinejad’s shock second place in last week’s first round of the election to rigging and voter manipulation by powerful hardliners.

But the earnest support that Ahmadinejad receives from many a man in the street is a clear signal that voters here are expecting far more from their president than highbrow ideological musings.

Rafsanjani has talked diplomacy, new approaches, globalization. But what many Iranians want is bread, butter and, as one Ahmadinejad aide asserted, “high oil prices to end up on their plates”.

“The next president needs to increase salaries and pensions of people with low incomes. They are capable of anything if they want to,” said Abdollah Karampour, a 50-year-old who spends his days selling bus tickets from a scorching cubicle.

Such viewpoints could fatally undermine an “anti-fascist” alliance established by Ahmadinejad’s foes, fearful of the prospect that every one of the Islamic republic’s institutions could fall into the hands of the religious far-right.

And even if Rafsanjani can pull off a victory, he will not be able to ignore the legacy of the bitter election — which had been tipped as a clash of right-left ideologies but ended up as a cry for better standards of living.

After all, the third place in the first round of polling went to Mehdi Karoubi, a moderate cleric who promised 500,000 rial (55 dollar) monthly handouts to all Iranians over 18.

Economists labelled it as fiscal madness and Karoubi had been written off ahead of the election — but his offer won huge support in the villages.

“It’s a serious warning to officials,” commented Amir Mohebian, political editor at the conservative Ressalat newspaper.

“Poverty is a serious problem, and many people would rather have something on their plates than political speeches.”

According to Iran’s Central Bank six million Iranians scratch out an existence from below the poverty line, that is 220 dollars a month in towns and 100 dollars in villages. Unofficially the figure is put at 15 million out of a population of 67 million.

Much will depend on whether Ahmadinejad has managed to rally more support, and if Rafsanjani’s camp can inspire fear. The result is unpredictable, given that both are also facing an increasingly sceptical and very unpredictable electorate.

“They are all the same, they’ve been lying to people for 25 years and never keep their promises,” lamented 28-year-old Mojtaba Zahedi, who uses his motorbike as a taxi and works a 12 hour day.—AFP

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.