Special report: Sindh's high stakes in oil and gas

Sindh's claim over a greater share in the NFC Award is bedded in its oil and gas reserves. With the province already supplying 23pc of Pakistan's oil and 67pc of its gas, future discoveries can reopen constitutional questions.

In the midst of a gas supply crisis across Sindh in December last year, Chief Minister (CM) Murad Ali Shah lambasted the federal government in a press conference outside the Sindh Assembly.

“How is it possible in a welfare state ... that the people of Sindh are first deprived of water and now being denied gas supply,” he boomed. Ministers accompanying the CM added the federal government was committing a “flagrant violation” of Article 158 of the Constitution, arguing that it was either incompetent or it was wittingly deviating from the Constitution.

The crisis rumbled into this year.

In January, Shah would go on to call for revisiting the criteria of the National Finance Commission (NFC) Award — the instrument used to distribute taxes collected among the provinces. The CM argued that more weightage ought to be given to the quantum of revenue generation rather than the provinces’ population.

Till now, no formula has been agreed upon on a revision of the NFC Award and the status quo persists.

But the matter of oil and gas exploration and production in Sindh has come to the fore once again after Prime Minister Imran Khan (perhaps prematurely) made the claim that Asia’s largest gas and oil reserves might soon be discovered near Karachi.

The claim of better days ahead ought to have provided a silver lining in the distance, but it also set alarm bells ringing: will Sindh even get its due share if these reserves were successfully explored? Will the NFC Award still enjoy constitutional protection? And is the idea of rolling back the 18th Amendment linked to potential discovery of new oil and gas reserves? Will the balance of power between the centre and provinces once again be altered?

NFC award, oil and gas

The Pakistani constitution stipulates that whatever grows or exists above ground level is an asset of the province, and what is found beneath the core of the earth is considered to be the asset of the federal government. In the same manner, whatever exists within 30 nautical miles of the coast is under the jurisdiction of the provincial government but the centre stakes claim to whatever lies beyond that.

This creates a substantial dichotomy, particularly with regards to the 18th Amendment to the constitution.

The 18th Amendment stipulates that the collective provincial shares in the divisible pool may not be reduced from 57.5 percent. The amendment, of course, provided unprecedented protection for the provinces but it also put pressure on the centre’s finances — how will it foot the substantial wage bill of the bureaucracy, the armed services as well as federal debt servicing?

Of late, the government in Islamabad has been broadcasting the financial crunch it finds itself in. One way out of the mess — and arguably what the government is banking on — is if large oil and gas reserves are successfully found off the Karachi shore. And while there is great prosperity to look forward to if this situation turns into reality, there are finer matters also at play.

Potential oil and gas discovery in Sindh directly impacts the power relationship between the centre and the provinces. The 18th Amendment left in its wake some unresolved political questions — for example, in the event of successful oil and gas exploration, what would be the respective mandates of the centre and the provinces?

At present, things are shrouded in confusion. At the centre, matters pertaining to oil and gas are dealt with by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Resources. Sindh, however, has no dedicated mechanism. It currently has an energy department that deals with these matters which is dealt with by the CM.

With Karachi’s population and internal migration towards the city increasing at a great pace, the matter of who can and who cannot benefit from oil and gas resources will surely come into sharp focus. Central to that is power: who wields what and how much. Fears in Sindh about the rollback of the 18th Amendment are premised on the assumption that power and finances may once again be stolen from provincial and local administrations.

Then there are issues of how the NFC Award is calculated.

Consider, for example, the fact that taxation falls in the realm of the NFC Award but profits do not. So, taxes collected from the sales of oil and gas shall be distributed among provinces. While Sindh would ultimately be managing and operating oil and gas operations, it has no legal claim over resources found beyond 30 nautical miles and therefore, no claim to a share in the profits.

It is for this reason that CM Shah, after the last meeting of the Council of Common Interests (CCI), has been emphasising more on the fate of oil and gas than the NFC Award itself. The province’s position now is that more refineries need to be built in Sindh’s cities other than Karachi. This reflects the province’s direct interest in the matter of exploration, production and consumption of oil and gas. If large oil and gas reserves do become a reality, then Pakistan needs to attempt to harmonise the distribution of power, resources and jurisdiction between the centre and the provinces.

Discovering oil offshore

Off-shore Pakistan is divided into two basins: the Indus Basin and the Makran Basin, separated by the Murray Ridge.

Mainly driven by its similar geology with other deltas rich in hydrocarbons, off-shore areas of the Indus Delta have indicated a tremendous potential of oil and gas in seismic surveys. The interest in the Indus Delta is more recent — only since 1961 — but the poor success rate off-shore in this delta has been a cause of discouragement.

Moreover, the cost of such projects is enormously high — a single exploration well off-shore can cost in the range of 60 million to 200 million dollars. (The high costs and low yield resulted in British Petroleum making an exit from Pakistan.) A list of major exploratory wells that had been drilled off-shore in Pakistan until 2010 is shown in Table 2 [see overleaf]. The spud dates and completion dates are also mentioned. None of these resulted in any substantial discovery.

As of 2013, the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Resources has given 16 licenses for gas exploration in the Indus Basin, while no licensees are working in Makran. Private companies are still interested in exploring, but the high risk and cost, and the time required relative to onshore exploration, repels potential investors. If the government wants to exploit off-shore areas, it must encourage public-private partnerships and share the risks.

Sorting the wrangles

Any potential discovery of oil and gas will inevitably open a can of constitutional worms. And while debates will generate polar responses, the solution perhaps lies somewhere in the middle. What is perhaps non-negotiable and enjoys constitutional protection is the share of province in the divisible pool. But what of the other money earned? What kind of benefits can the province of Sindh, in particular, receive from any potential new discoveries?

Many matters are linked to the centralisation of power and the decentralisation of finances.

But problems exist in corporate taxation, for example. Karachi often claims that it enjoys the lion’s share in generating finances for the country. But the devil in the detail is that corporate agreements are often signed in Karachi but the corporate entity has a footprint across the country. Taxes generated, therefore, might technically not be from Karachi.

Then there is the question of staff and labour hired. In places such as Dadu and Khairpur, locals are often excluded from employment in oil and gas projects. Such complex details have often evoked sentiments of disenfranchisement, be it in Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or Balochistan — will the locals be considered part and parcel of the bounty we are being promised exists?

Sindh is already making moves to secure a favourable outcome. CM Shah has been insisting, for example, that the NFC Award should also include a stipulation for yet-to-be-discovered resources. But the answer to many of these queries is bedded in sorting out the respective mandates of the centre and provinces. A harmonious outcome to the question of power might be a necessary pre-condition for the exploration of oil and gas because that is what will ultimately breed trust among the centre and the provinces.

Nadeem Hussain is a research fellow at the Institute of Business Administration, Karachi.

Ahmed Yusuf is a member of staff. He tweets @ASYusuf

Published in Dawn, EOS, May 5th, 2019

A brief history of exploration

To contextualise the present, one must look back and understand the past. Eos presents selected passages from the recently published book, 'The Economy of Modern Sindh' by Ishrat Husain, Aijaz A. Qureshi, and Nadeem Hussain.

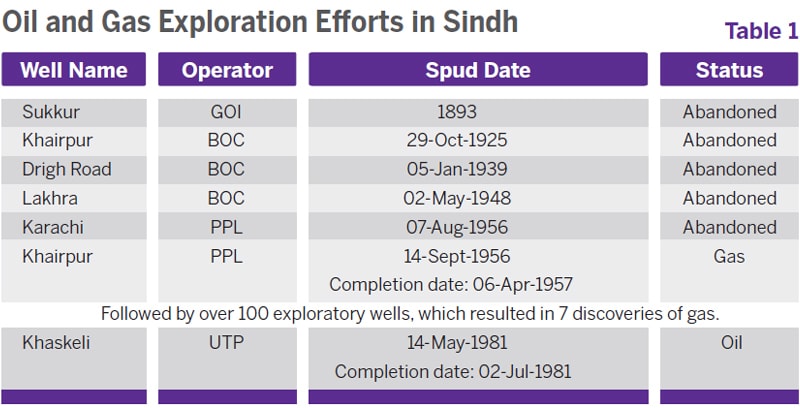

Before the late 1950s, Sindh was not known to be rich in hydrocarbons. The government of India began exploratory activity in Sindh in 1893 by drilling a well in Sukkur, which did not result in any yield. The next attempt for the search of oil and gas in Sindh began after an interval of more than three decades by the Burmah Oil Company, a Scottish oil business based in Khairpur. Like its predecessor, the project did not result in discovery of oil. Until 1947, exploration was underway mainly in Punjab, where four oil discoveries were made since the initiation of the process in 1868.

After the creation of Pakistan, the nascent country strove to meet its energy requirements independently. Pakistan Petroleum Limited (PPL) was founded in 1950. Its first project comprised of drilling near the town of Sui, Balochistan, leading to the discovery of the largest gas field of the country.

Several players were involved in oil and gas exploration in Punjab, Balochistan, and Sindh. Table 1 shows, however, that no gas was discovered in Sindh until 1956 and no oil was found until 1981.

In 1957, Pakistan Petroleum discovered natural gas in Khairpur. In the same year, gas reserves were found both in Mari (of 6.3 trillion cubic feet, the second largest gas reserves in Pakistan) and Talhar by Pak-Stanvoc Petroleum Project (a joint venture of the Government of Pakistan and Esso Eastern Incorporated). The next year, Burmah Oil Company drilled and discovered some gas in Lakhra, Badro, and Phulji Dadu. And in 1959 Pak-Stanvoc Petroleum Project discovered a small gas reserve in Bathoro and some gas and oil in Nabisar. The project also attempted to drill oil in Badin, but did not discover any reserves. In the same year, PPL discovered a meagre amount of gas in Kandhkot and Mazarni.

However, during 1960-70 gas exploration shrunk and the focus shifted to oil exploration across Pakistan. The companies that were involved in exploration during this period were Sun Oil Company (SOC), ESSO Eastern Inc. (ESSO), and the Oil and Gas Development Corporation (OGDC, established in 1961). Sun Oil Co. focused mainly on coastal areas; it drilled wells in Patiani Creek and Dabbo Creek in 1964, and Korangi Creek in the following year. The oil exploration proved fruitless all over the country. 453 exploratory wells were drilled out of which 60 were located in Sindh and, as a result of these efforts, only one small gas field was discovered at Sari, Sindh, by OGDC in 1966.

In the decade 1970-80, 417 exploratory wells were drilled out of which 127 were in Sindh. Only five significant gas fields were discovered, out of which two were located in Sindh. The two fields where oil was discovered were both in Punjab. Companies that were most active during this period in Sindh were PPL, ESSO, OGDC, and Union Texas Pakistan (UTP). Off-shore drilling was carried out by the first time in Sindh by Wintershall, a German company. The company drilled Indus Marine A-1 and Indus Marine B-1 in 1972, and Indus Marine C-1 in 1975. OGDC drilled and found gas in substantial amounts in Kothar in 1973 and Hundi in 1977. Husky Refining Company, an American company, drilled a well in Karachi South A-1 in 1978 and also located gas. However, no major discovery was registered.

During 1980-1990, widespread exploration for hydrocarbons was carried out in Pakistan. Some 5,775 wells were drilled, out of which 1,724 were located in Sindh and resulted in the discovery of large oil reserves. The companies leading the drilling expeditions were UTP, ESSO, PPL, and OGDC. Khaskheli Oil field was a breakthrough discovery in the coastal district of Badin by UTP in 1981. In 1984, Tando Adam oil field was also drilled and completed. This was followed by more significant oil discoveries in the Laghari and Mazari fields.

In the 1990s, a total of 31 oil fields were discovered in Pakistan, out of which 23 were in Sindh (the rest being in Punjab). Meanwhile, the contribution of Sindh in gas production exceeded Balochistan’s for the first time. In 1990, the third largest gas field in Pakistan was discovered in Qadirpur by OGDC. In the same year, Kadnwari was discovered by LASMO (now Eni). This discovery was followed by Miano by OMV in 1993, Bhit by LASMO in 1997, Sawan by OMV in 1998, Zamzama by BHP in 1998, and Mari Deep by MGCL in 1997-98.

Recent developments

While Pakistan has shown a subpar success rate of oil and gas discovery of 1:3 (compared to the world’s 1994 rate of 1:1.3), the country has yielded significant amounts in recent years. In the span of three years since 2013, 83 oil and gas discoveries have been made. These have added 631 million cubic feet per day (mmcfd) gas and 27,359 barrels per day (bpd) crude oil to the total reserves of Pakistan.

In 2015, 1,095 bpd crude oil supply was found at Tando Allahyar by the OGDC. In June 2016, a total number of six discoveries were made across Pakistan, adding 50.1 mmcfd of gas and 2,359 bpd of crude oil to the existing production levels. Out of these six discoveries, four were made in Sindh. This included one discovery each by the PEL and the UEP and two by the OGDC. These discoveries comprised of more than 63 percent of the gas, but only 14 percent bpd of crude oil. The other two discoveries were made in KP by MOL Pakistan.

The focus of oil and gas exploration has now shifted from Sindh to the other provinces. Fifty new exploration blocks were created in January 2014, of them only 12 percent lie in Sindh.

Production and consumption of oil

From almost no production in 1980, Sindh started providing 47 percent of the total oil production of the country in 1985-86. This rate went up gradually to reach 65 percent in 2000. This has been dwindling and reached an all-time low of 38 percent by 2014. The absolute volume came down to 1.75 million Tonne of Oil Equivalent (TOE) in 2014 from 1.78 million TOE in 2005. The country as a whole has witnessed an increase of 43 percent in quantitative terms in the same period. Most of the new oil discoveries in the recent years have taken place in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), which has now replaced Sindh as the top domestic producer of oil.

KP has shown a steady rise in oil production since 2005, while Punjab’s yield has declined and has been constant from 2010 to 2014. Punjab’s trend in oil production over the years follows a set pattern showing a period of steady rise followed by a gradual decline. The resource-rich province of Balochistan, meanwhile, displays a dismal trend — its production has been constant and significantly less than the production of all other provinces.

As the industrial and commercial hub of Pakistan, the consumption of petroleum products in Sindh was at its peak during 1950s. But as economic growth slowed down for a variety of reasons, there has been a gradual decline and the share of petroleum consumption is down to 23 percent compared to 42 percent in 1980-1981.

In absolute terms, oil consumption has risen 2.8 times during this period. For the last two years, the precipitous decline in international oil prices has boosted the domestic demand and furnace oil (FO) has once again became an acceptably priced fuel for power generation. Substitution of FO by RLNG for power generation plants currently under way would, however, reduce the demand for imported FO. Domestic refineries could produce the required quantities.

As income per capita and therefore purchasing power rises, the demand — direct and indirect — for petroleum products also rises. But price elasticity does play a key role in consumption. Oil consumption in Pakistan is related to oil prices: more consumption happens as prices drop. The trend line of GDP also moves in the same direction showing positive income elasticity of demand.

Nadeem Hussain is a research fellow at the Institute of Business Administration, Karachi.

Ahmed Yusuf is a member of staff. He tweets @ASYusuf

Published in Dawn, EOS, May 5th, 2019

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.