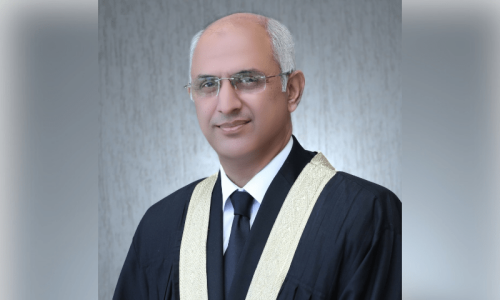

WHAT started out as a political firestorm has ended, eight years later, with a whimper as the Supreme Court on Thursday finally wrapped up the so-called Memogate affair. The case — which was built on the claim that elements in the Asif Zardari-led government sought Washington’s help against the Pakistan Army — was concluded by Supreme Court Chief Justice Asif Saeed Khosa who poignantly wondered if the state, the Constitution, democracy and the armed forces were so fragile as to be shaken by a mere ‘memo’. That none of the overzealous petitioners who pursued this case were present when the apex court delivered the order is ironic, as a recap of the events is dominated by flashbacks of a national frenzy around the allegedly treasonous memo which was exploited to deepen the civil-military divide. The court has rightly left it to the government to decide if it wants to proceed against Mr Husain Haqqani, who was accused of writing the memo to the then US military chief Adm Mike Mullen in which he allegedly sought US help to avert a possible overthrow of the civilian government by the military following the killing of Osama bin Laden in May 2011. But the conclusion of this case presents an opportunity for self-reflection on several fronts: should the judiciary under Iftikhar Chaudhry have jumped to act as referee in the Memogate matter, when the government at the time had already announced a probe? Was it appropriate for Nawaz Sharif, who has since acknowledged his mistake, to use the memo as an opportunity to lead the charge and allege treason against the PPP government? After the passage of many years, was it the responsibility of then chief justice Saqib Nisar to revive the Memogate controversy using his powers of suo motu?

Despite the formation of a commission, court summons for civilian and military leaders, and breathless reporting by the media, the scandal did not achieve anything other than the sacking of an ambassador. At the heart of the issue lies the notion of the separation of powers, which divides the responsibility of the state between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary — a framework which continues to be murky for the state today. As Chief Justice Khosa noted at the conclusion of the hearing, nothing needs to be done by the court at this juncture. It is now — as it always was — a matter for the government to deliberate on.

Published in Dawn, February 16th, 2019