These women stayed in abusive marriages because Pakistan failed them

Dania endured violent beatings during her pregnancies. But leaving was not an option; she was sent back to live with her tormentor

In the six years Dania has been married, she has spent four-and-a-half at her mother’s house. Her children were born here after all — though their father never witnessed the births.

“He began hitting me as soon as I was married,” she says. “Even when I was pregnant with my first daughter.”

Each incident resulted in the same play of events: Dania would rush to her mother’s house, only to end up going back — sometimes of her own accord but often on the persistence of her community and its elders.

Her parents told her divorce was a terrible idea. “It’s better for a family to settle down,” they told her, “Hum izzat wallay log hayn [We are respectable people]. Such people do not have divorced daughters.”

The issue was discussed at the village panchayat, which decided she should go back to her husband immediately. Each time she approached them for help, she was given the same ruling: “These things are not unusual, they happen in homes.” It was better, the panchayat decided, for Dania to return to her husband.

Dania did, as she had before, but her husband was not going to change. When she was pregnant with her third son, her husband added to the years of bruises and pain by kicking her down a flight of steps. And once again she left — only to return.

Dania’s story is interrupted by the cries of son. The impact of his mother’s plight is clear on his face. He cries when she talks about the violence; when she lifts up her shalwar to show the scars on her legs. He continues crying as his elder sister sits still, the fear dark in her eyes.

Her most recent return to her husband's home — her home — was marked by a particularly gruesome act. Dania's parents were informed by a neighbour that their daughter had been hospitalised because her husband had poured bleach into her mouth. It was another chapter in the sordid episodes of abuse that have come to define Dania's married life.

Efforts to have her husband held accountable with the local police have borne no fruit. The police too encourages the two parties to reach a compromise. According to Dania, they said the crime of making her ingest bleach "did not seem like one to warrant punishment".

“I work now,” she says, gesturing at small decoration items scattered on the bed at her mother's home. “I am feeding my children.” As always, she is pushing for divorce but her family is not convinced. They don’t want her to live with her husband, but they are not ready for her to end her marriage either.

“We have our family’s honour to protect,” her brother says. The complicated notion of honour has already had a ripple effect in the family. Dania’s frequent returns home have brought about an unintended consequence for her family — one of her sisters is no longer married.

“Another one of my sisters was married for 10 years," says Dania's brother. "After we began police proceedings against her husband for attempted murder, that sister was divorced. Her in-laws said our family attacks in-laws and her marriage ended.”

While Dania is adamant she will not return, the likelihood is that after the dust settles, her family will once again push her in that direction.

Her brother places his faith in God, who he believes will fix everything.

“Maybe He will make them more human,” he suggests, “Maybe her husband will realise he had children with her. We have hope, we don’t want her divorced.”

Things work in a "set way" here and societal pressures are heavy. Her brother says that’s because it’s not a city; it’s a village. When a married woman in their village stays at her mother’s house for a long period of time "it is a terrible and dishonourable thing”.

“We have a saying,” he goes on to explain. “Once a woman leaves her mother’s house as a bride, she can only return in a coffin.”

So would he rather she die than get divorced?

As if wondering the same, he slowly nods. “For us, her getting divorced would be much worse than her dying.

Click the tab below to read her story.

Behind the closed doors of their picture-perfect life, her husband abused her regularly since a week after their marriage

Outside a park in Lahore, Akifa looks around to see who is watching and quickly steps out of her car. She cannot meet at her house, where it would be impossible to discuss her ordeal. Other public spots, she says, are too crowded and make her uneasy.

On the surface, her life is textbook perfect. She secured a masters degree at a time when most women barely made it through their intermediate schooling. Her family is well off, and her husband’s oft-touted story of rags to riches impresses many. “People look up to him because of his humble beginnings,” she says, “He is a self-made man.”

But he is also an abuser. Behind the closed doors of their picture-perfect life, he has been abusing her regularly since a week after their marriage.

At first, it was emotional abuse; taunts and nasty words that were always punctuated by the vilest curse words. "He didn’t care where we were, or who were with,” Akifa says.

Then, he beat her. "He didn’t care if it was a public place, that we were at a friend’s place or if my family was around…”

Her plans to work and gain financial independence were also all in vain, because her husband didn’t approve. "Working women are disgusting and disgraceful,” he reminded her.

Akifa started working from home, only to have her earnings taken away by her husband, who was jobless at the time.

Throughout this misery, Akifa didn’t resist. She didn’t know how to, she says. Until her marriage, she had never imagined that someone could speak with their partner in such a crude manner; no one in her family had.

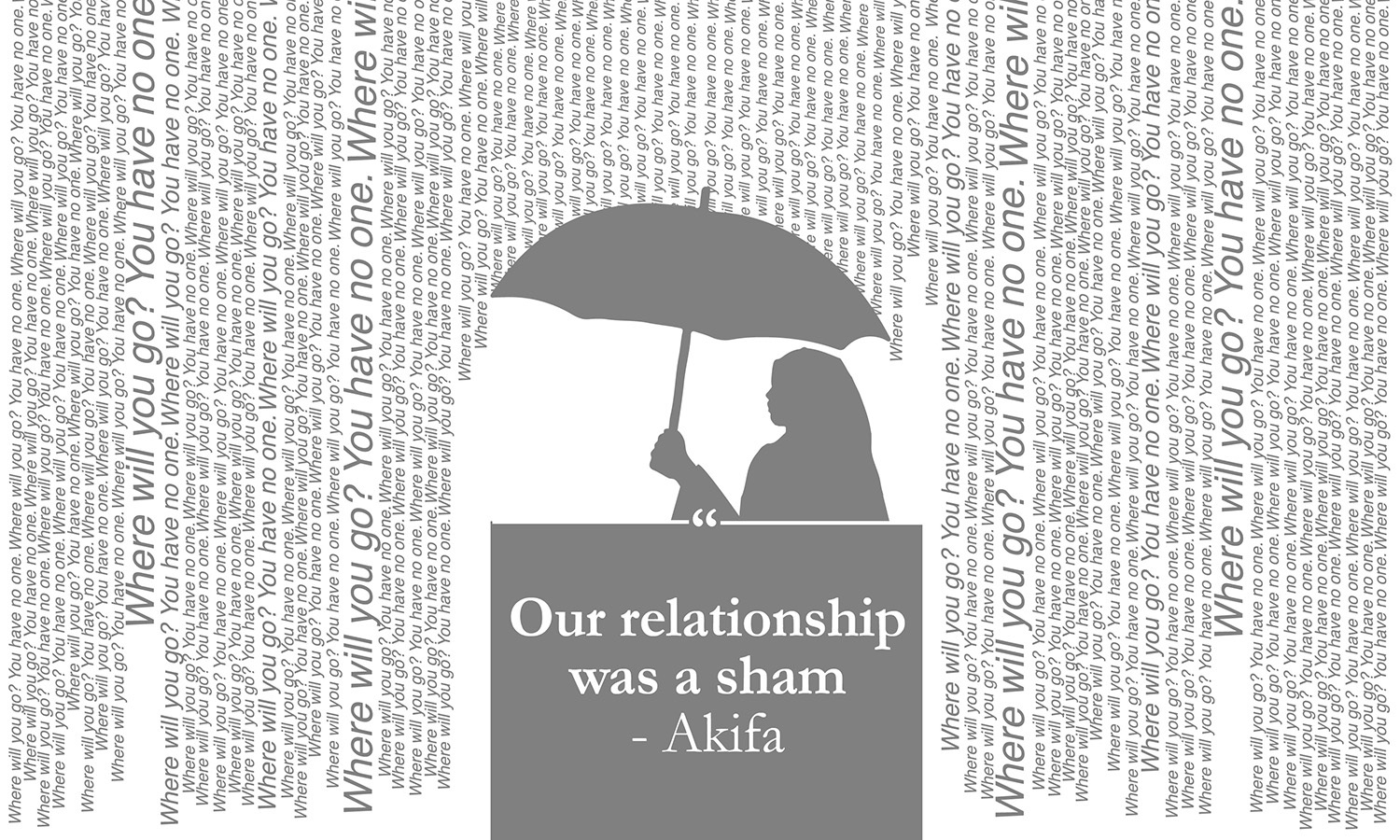

Each time her husband got angry, she was paralysed with fear; too scared to do anything. Several times he kicked her out of the house, jeering at her with the same words: “Where will you go? You have no one.” He took advantage of her father's death and her estranged relationship with her siblings.

She thought about it giving him a taste of his own medicine, but then asked herself, “What woman beats up her own husband?”

It wasn’t until one of her children realised what she was going through that the abuse stopped. 18 years into her marriage, Akifa was arguing with her husband over their son’s medical treatment. She wanted to go to a reputable physician, but her husband was convinced a quack would be enough.

Somewhere during the argument he began to hit her.

But her daughter barged into the room and blurted, “Why don’t you divorce this man? Why don’t you leave him?"

Leaving was never an option for Akifa. Her husband had not only shattered her self-worth, he had also ensured she remained firmly dependent on him for everything.

For many women, financial dependence becomes a core reason they can never leave. When children are born, matters only get more complicated.

Akifa thought a lot about how her children would be taunted if she left him and they grew up without their father. She was scared of being labelled a 'bad mother'.

She had nine siblings, but not one intervened when her husband misbehaved with her, even if it happened right before their eyes.

As a result, she would not discuss the beatings with them. She had learnt her lesson when she once reached out to her sister, only to receive a list of reasons why it would be better to stay. “‘Respectable women’ do not leave their husbands and their homes,” she was told.

But unlike anything before, her daughter’s intervention worked. The beatings stopped. They continued living under the same roof, but his behaviour changed. Her daughters, who started doing odd jobs years ago, slowly helped their mother break free of her financial dependency. Despite their father's wealth, the girls hurried to stand on their own.

She considers theirs to be a ‘sham relationship’ only existing because societal pressure kept her locked in. But she is relieved the abuse has come to an end.

“We got out of a situation where one man was pretending he was God,” Akifa reflects.

Click the tab below to read her story.

Abused by her husband, Fatima chose the option of leaving. But where could she go to hide from her own family?

Fatima ended her marriage four years and a daughter later because of domestic abuse. That was in 1993. 15 years later, in 2011, she was subjected to it all over again, this time by her brother.

The trouble, which continues till today, began when her brother returned to the country. Other than Fatima, her entire family was settled in various parts of the world. He started hitting and abusing over petty issues. When she tries to shut herself in her room, he breaks down the door.

As a woman abused by her husband, Fatima chose the option of leaving. But where could she go to hide from her own family?

Her sisters tried to intervene, but they lived abroad, and were soon preoccupied with their own problems and worries. Her father is aware that her brother beats her, but he does not offer her a shoulder to cry on.

“He is a passive observer,” she says.

Fatima has contacted the police and asked them to help. She has told them her brother tried to kill her, and once almost choked her to death. But their response was lukewarm.

“He hasn’t killed you yet,” the policeman had stated at the time. “You’re still alive, aren’t you?”

She began feeling isolated. People who had pressured her into making decisions that conformed with society’s view of a woman’s life were not around when she had to bear the brunt of those decisions. Meanwhile, her brother showed no signs of stopping.

Four years later, he still thinks he can do anything with her. “I don’t have a husband and I am alone, but does that mean I am not human?” Fatima cries.

Beyond the physical abuse, her brother has destroyed her emotionally. She lives in constant fear of him ending her life, as he has gone as far as trying to run her over with his car.

"I live in constant fear in my own home,” she says. Even now, the conversation is taking place behind closed doors, as she has told her family she is having a simple chat with a friend. Tea is served, doors are carefully locked, and the façade is maintained throughout.

No matter how bad the abuse gets, the mantra haunts her. She is told to act with patience, that it could be worse. Despite her resolve to fight and stay strong, she is battling abuse alone, a single mother raising a daughter. There are times, Fatima says, when all of that resolve fails, all her strength diminishes, and she feels nothing more than a living corpse.

Click the tab below to find out more.

These women share harrowing stories of abuse.

Their families repeatedly shunned them, so they went back to their husbands till they could not bare the violence anymore. They now live in a shelter.

If you or someone you know is subjected to domestic violence, you can do something about it:

Punjab

The Punjab Commission on the Status of Women

All incidents of domestic violence can be reported to the Punjab Commission, from anywhere in the province. The Commission then transfers your case to the police. If you need guidelines on how to file a First Information Report (FIR) or are having difficulty getting a case registered, you can contact them for further help.

You can also consult their Helpline Guide before calling.

Contact: 1043 (toll-free)

Sindh

Citizens-Police Liaison Committee (CPLC)

The CPLC has opened a Women Complaint Cell where all incidents of domestic violence can be reported. The complainant is required to come to their office after registering a complaint to fill out some paperwork. The Cell then guides you on how to take your case further.

Karachi: 021 3568 3333 Hyderabad: 022 9260222

For specific regions in Karachi, check CPLC's website.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Social Welfare, Special Education And Women Empowerment Department (SWKPK)

SWKPK runs women crises centres in Peshawar. They also provide institutional and residential care for run away and destitute women, and work towards their rehabilitation in the society.

Peshawar: 091 9211700

Balochistan

Aurat Foundation

Aurat Foundation is a non-profit, non-governmental organisation monitoring and documenting incidents of violence against women. In addition to having offices in Islamabad, Lahore, Karachi and Peshawar, it is also one of the few such NGOs running in Quetta.

Quetta: 081 2821282

There are a number of organisations working in different capacities to help women and fight violence against women.

Madadgaar

Madadgaar is Pakistan’s first helpline for women and children suffering from violence, abuse and exploitation. Anyone can call their hotline (1098) to report an incident, or sign up for a virtual counselling session.

War Against Rape (WAR)

Established in 1989, War Against Rape provides crisis intervention to the sexually abused women and children, including free services like legal aid, psycho-therapeutic counselling and basic medical assistance. It is run by people of all genders who participate in a governing body, and it has an aggressive advocacy component geared towards spreading awareness and changing legislature.

Sahil

Sahil has been working for the last 20 years on child protection especially against child sexual abuse. They offer free legal aid and free counselling, and work with primary and secondary schools teachers, organisations, community members, parents, police and lawyers.

Tehrik-e-Niswan (The Women’s Movement)

Tehrik-e-Niswan is best known for its feminist and politically conscious plays about the plight of women and other oppressed groups. The group initially emerged out of the first All Women’s Conference in 1980, with a focus to organise seminars and workshops on issues relating to domestic violence. Within a year Tehrik had moved away from seminars towards cultural and creative activities like theatre and dance to spread its message.

Women's Action Forum (WAF)

Commonly referred to as WAF, the Women's Action Forum does active lobbying and advocacy on behalf of women in Pakistan. It stages demonstrations and public-awareness campaigns, and picks up issues challenging discriminatory legislation against women, the invisibility of women in government plans and policies, the exclusion of women from media, sports and cultural activities, dress codes for women, violence against women and the seclusion of women.

WAF has a presence in several cities, and is non-partisan, non-hierarchical and non-funded. It allies itself with democratic and progressive forces in the country and has historically linked its struggles with that of minorities and other oppressed peoples.

Bolo Bhi

Bolo Bhi ('Speak Up' in Urdu) is a not-for-profit geared towards advocacy, policy and research in the areas of gender rights, government transparency, internet access, digital security and privacy. Bolo Bhi hosts digital security trainings, advocates for better laws, and tracks online and offline violence against women.

Digital Rights Foundation

Digital Rights Foundation aims to strengthen protections for human rights defenders (HRDs), with a focus on women's rights, in digital spaces through policy advocacy & digital security awareness raising. They also deal with workplace harassment and cyber-harassment, holding workshops and trainings to help women identify instances of harassment, and make them aware of their rights.