NEW DELHI: For India to grow rich, must its citizens become more honest? It's a question that preoccupied Kaushik Basu, the government's chief economic advisor, during his term in office.

“We talk of good moral values as useful in themselves, but the fact that economic development and economic functioning can depend on these values is usually pushed aside,” said Basu, who left his post last month.

Better behaviour such as respecting meeting times and public spaces, as well as more moral behaviour in terms of less cheating or thieving, are both desirable and necessary for economic development, he believes.

“A modern market economy cannot function without a modicum of altruism and trustworthiness,” said the academic who once wrote a research paper called “Why we don't try to walk off without paying after a taxi ride.”

It concluded that “when people are not automatically fulfilling contracts, life becomes more cumbersome and costly.”

In India's case, a lack of trust due to pervasive cheating brings with it enormous costs.

“The biggest cost is that you don't start up activities because the transaction costs are so high,” Basu told AFP from his office in the finance ministry before his departure.

Trading partners may cheat, delay or not deliver, while staff must be closely monitored when handling stock, cash or customers. Checks and balances consume substantial amounts of time and money.

In a country where the outgoing head of a government anti-graft body said in 2010 that one third of Indians were “utterly corrupt,” they are particularly costly.

“I can cut deals much more comfortably in Japan, for example,” Basu explains.

The result in India is that entrepreneurs promote family members before other candidates, or do their best to keep business within their own ethnic or religious communities.

“In a big society and to be a vibrant economy, you need anonymous trust,” he adds.

Japan and South Korea's example

While Basu says it is much easier and cheaper to cut a deal in Japan than India, his research into behavioural changes during periods of economic growth showed him that it was not always like this.

He refers to an account 100 years ago by a frustrated European engineer in Japan named Kattendyke who wrote about supplies not arriving on time, workers showing up once and never returning, and a pervasive lack of punctuality.

“When you block out the Japan, it could be India,” added the economics professor, who is now returning to academia and his former role at Cornell University in New York state.

The stereotype of diligent, punctual workers in fellow Asian tiger South Korea was also challenged.

“I got lines from the 1950s, of Europeans describing the sloth and laziness of the South Koreans. But now they are the most industrial and hard-working people. And this happened over no more than five decades,” he told AFP.

The words at once confirmed his belief that traits such as punctuality or personal integrity were learned, not hard-wired.

There also appears to be a link between a better physical environment — often the consequence of economic development — and better behaviour.

Bureaucrats take less bribes in cleaner offices, some research has suggested, while Basu joked about the example of the “clean and well-maintained” environment of the New Delhi metro.

“People in Delhi when they are in the metro, in this lovely setting, they behave much better,” he says. The punchline is that all their bad behaviour is reserved for when they come to the surface.

India's future

So is India, which has enjoyed an economic boom since pro-market reforms in the 1990s, becoming a place where trust between individuals is increasing?

Despite the huge public-sector corruption scandals of the last few years, Basu believes so.

“My general sense is that it is improving and it's something to do with the market economy coming in and beginning to function better,” he states.

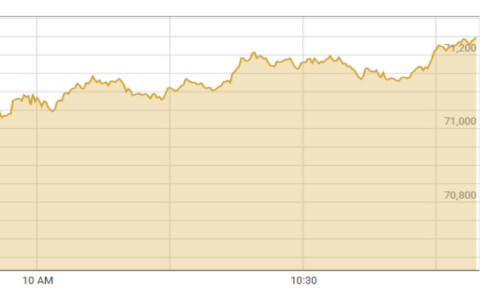

One indication is the savings rate, which shot above 30 per cent to East Asian levels around 2003 as Indians embraced personal banking. He also believes from his own experience that people are more reliable than 20 years ago.

“Both of them have a common root,” he says. “You save more when you are more far-sighted and looking into the future.

“You deliver better products even without supervision from the same motive.

You are interested in your profit one year down the road and you want to build up your reputation.”