“The education department acts more like an employment agency than a service delivery department,” says a former education secretary for Sindh who asks not to be named.

Pakistan’s education budget has evolved as a slush fund for politicians to generate profits for themselves and political supporters. The bulk of the provincial budgets – around 85pc – are spent on salaries for teachers many of whom are not found in schools.

In Sindh, 40pc of teachers are ghost employees, according to the current education secretary.

“The entire system is patronage-based, not efficiency-linked,” continues the former secretary, “MPAs lose elections when they fail to distribute jobs; not when schools are dysfunctional.”

MPA refers to a member of the provincial parliament.

According to a report by the Society for the Advancement of Education (SAHE): “Historically, politicians have used teacher recruitment as a form of political patronage.”

“Some teacher posted in, say, Chachro in Tharparkar district is not even physically living there. He or she could be living in Karachi, or Hyderabad, or outside Pakistan, but drawing a monthly salary,” explains Nadeem Hussain of the Sindh Reform Support Unit, which is a part of the education department that leads reform efforts.

The SAHE report explains the link between teachers and politicians. First, because teachers are educated, politicians tend to use them as political organisers in rural and semi-urban areas. Second, teachers are posted as polling staff on election days. Finally, teachers unions are associated with political parties – although they don’t necessarily need the parties to exercise political clout.

However, the interference of politicians does not end with the recruitments and postings of teachers.

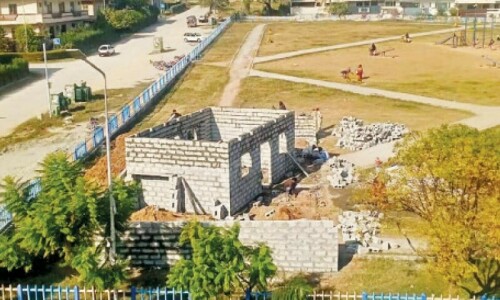

Politics also plays havoc with the 10pc of the education budget spent on “development”, referring to the budget intended for building and maintaining schools.

“Money is requested for ‘education’ and once it is allocated then the specific needs are figured out,” says Salman Naveed of Alif Ailaan.

This allows politicians to access amounts at will.

“The so-called ‘annual development plan’ does not name a specific location for the schools but makes umbrella grants for 50 or 60 schools at a time,” explains Muhammad Anwar of the Centre for Governance and Public Accountability (CGPA), “Throughout the year, the chief minister uses these funds to win over MPAs.”

No wonder then that the bulk of the money is spent in the districts of the more powerful legislators.

“These days, most of the budget is going to Nowshera because the chief minister of KP is from there. Five universities are being established there,” Anwar says, adding “but in Tor Ghar, there is not a single girls’ high school”.

Tor Ghar was a tribal area until 2011 and is today the smallest district in Pakistan.

This leads to an irrational emergence of schools or buildings. “Some villages have three schools and some have none,” points out Managing Director of the Sindh Education Foundation Naheed Shah Durrani.

According to the SAHE report, “In Balochistan, funds provided to members of the provincial assembly are mostly used in the construction of education institutions whose feasibility has not been evaluated. Mostly the incentive is to give the contract to a favourite.”

Yet, despite all the money and political capital that is earned from this ‘development exercise’, the entire development budget is not spent every year.

This unspent development budget reflects Pakistan’s broken budgeting process.

This is because legislators are more interested in spending the money than in playing the oversight role that parliaments normally do in developed democracies.

In the United States, budget lines are parsed out and debated in detail by the members and staff of subject-specific subcommittees, full committees, and then the full chambers. A parallel process occurs in two houses of Congress over the course of a year, and then both houses must agree on one version of the budget. The fight is so intense that the American Congress has shut down the US government 18 times, most recently in 2013.

But in Pakistan – “we have the shortest time for a budget process in the world. Just 14 days. Members don’t have staff and are given huge budget books. They pick out things at random just to participate in the debate,” says Naveed.

Unless Pakistan fixes the way it plans and spends the education budget, doubling it may hurt more than it will help children.

Published in Dawn, July 4th, 2016