Footprints: Conversion by choice or force

A SERENE atmosphere prevails inside the shrine of Khanqah-i-Aalia Qadria Bharchundi Sharif, Daharki. The madressah next to it reverberates with the rhythmic hum of students reciting the Quran. The shrine’s caretaker, Pir Abdul Khaliq, is not in, but his 29-year-old son, Abdul Malik, is present on Thursday.

Wearing a cone-shaped head gear and a white flowing kurta, Abdul Malik appears oblivious to the uproar in the area a few days ago. Recently, the parents of a Hindu girl named Rani protested outside the Hyderabad Press Club demanding that their daughter — who they said was forcibly converted — be rescued from the Bharchundi Sharif shrine. Hailing from Jacobabad’s Kareemabad area, the girl belongs to the Bhaagri tribe, one of the poorest tribes in Sindh, say locals.

The scent of itar fills the room as Abdul Malik takes a seat across us in his well-furnished office inside the madressah.

A graduate in Islamic studies from the University of Damascus, he is learning the ropes of what he says “is my holy purpose to serve humanity”. Listening intently to the questions posed to him, he answers: “If someone wants to be converted, there’s not much we can do about it.”

(The madressah has converted 150 men and women in the past three years, says the person managing its administrative affairs. Rani is the first one to be converted this year.)

Adjusting his spectacles, Abdul Malik looks directly at me when asked why every Hindu girl decides to visit Bharchundi Sharif while thinking of converting to Islam. “Our job is to facilitate people. If they want to become a Muslim, we help them do that. However, we don’t take responsibility for who they decide to marry. The girl, especially in such cases, decides for herself.”

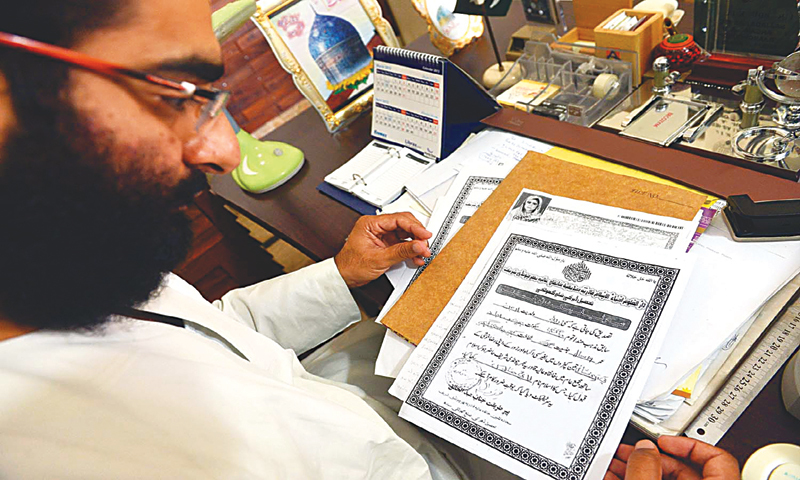

Rani was taken to the Sindh high court bench in Sukkur on Thursday morning as soon as her marriage certificate was made by her lawyer a day earlier. After coordinating for four hours, the three men — including her lawyer — accompanying Rani and her husband met us in a residential area in Pannu Aqil.

Rani Khatoon, as her name now reads on the marriage certificate, is said to be 19 years old. But she looks much younger as she sits quietly, holding one end of her dupatta tightly around her chin. The haq meher in her nikahnama is a mere Rs1,000.

Her eyes remain blank until one mentions her parents. That’s the only time her big brown eyes moisten. Otherwise, she gives monosyllabic replies when asked about her ‘love marriage’ to 22-year-old Mohammad Saroor. Sitting beside her, he’s asked by one of the men to close his buttons and appear “respectful”. Another quickly blames the weather.

Saroor says: “She used to sell clothes near our home in Jano Bhelo village while I’m a labourer and own a donkey. One day she told me she wants to marry me, and loves Islam, so we decided to marry.” When Rani was asked how while living in Jacobabad she knew she could take refuge at the shrine, she said a “friend informed her”, before once again lapsing into a state of blankness.

Whenever she’s asked about her decision to become a Muslim, she looks at the Bharchundi attendant, Abdul Wahid, who after every few minutes asks her to “khill” (smile).

When asked if she’s carrying her CNIC, she shakes her head in the negative. Her lawyer Mir Ali Mehboob interrupts, “An identity card is not needed in the high court when they know a couple wants to marry. Only a picture is needed which a court attendant matches with the picture we give them.”

A newspaper editor in Daharki says there are many cases of young girls marrying outside their community. “But this is more of a business, where everyone knows what’s happening but no one can report or speak about it openly.”

Dr Hari Lal, general secretary of the Upper Sindh Hindu Panchayat from Pannu Aqil, says, “Our courts have been hijacked. Until the system is shaken up nothing we do or say will matter. Why didn’t anyone inside the court demand to see her ID card or determine whether she is actually at an age to decide for herself? Even if a girl, as they tell us, decides to marry a Muslim of her own choice, why is she accompanied by armed men who keep an eye on each move of hers, as in the Rinkle Kumari case? If a party has to approach a court to solve matters, as in Rani’s case, why does the shrine goes to the higher courts every time? Why not a district and sessions court?”