The Democrats’ comeback

THE American mid-term polls have sprung no surprise. Opinion polls had predicted a sweeping win for the Democrats, at least in the 435-member House of Representatives. Quite early in the day, the Democrats wrestled control of the House from the Republicans. At the time of writing, the Democrats had won 228 seats — up from 201 — and the results for 12 seats were still awaited, while in the Senate the two parties were equally balanced with two results awaited. The return of the Democrats at the Congressional helm is a major development since they had traditionally been in control of the legislative branch of the government for over 40 years until the Republican breakthrough in 1994 when America experienced a swing to the right.

As Nancy Pelosi, poised to be the first female Speaker of the house, said, America has voted overwhelmingly for a change in direction. The major catalyst has been the war in Iraq. It is significant that the ‘catastrophe’ in Iraq — that is how most Americans see it today — has overshadowed the Bush administration’s success in some other areas such as the economy that has kept unemployment level to low levels and inflation rates modest. It is George Bush’s Iraq policy that took the country to an unwinnable war which has cost over 2,770 American lives with no gains in return, that has angered the voters. They now want a Democrat-controlled Congress to curb the president’s recklessness. The average American may not quite see it that way, but the fact is that since 2001 the Republicans under Mr Bush have controlled all the levers of power in Washington — from the White House to the heads of all Congressional committees on Capitol Hill, and had come to wield absolute power. The conventional checks and balances prescribed by the American constitution had been made virtually ineffective by the predominance of the GOP in all branches of government. By restoring the Democratic Party to its traditional majority in the Congress, the voters have ensured that the White House — at least for the remaining two years of the Bush presidency — will be more cautious in its approach. It is too early to say what change in policy in Iraq will take place considering the fact that the violence and chaos there cannot be reversed simply by an American pullout.

Though Iraq topped the voters’ concern, corruption and sex scandals also cost the Republicans much popular support. While the evangelists and the voters from the Bible belt registered their disapproval by staying home on polling day, the liberals rallied behind the Democrats to vote them into the Congress. The Republicans’ tainted record from the hubris of their army in Abu Ghraib and their anti-human rights record in Guantanamo to the financial and moral wrongdoings of their Congressmen and policymakers projected the party in a poor light and irked the voters. The elections have proved to be a referendum on George Bush’s presidency, and his party’s prospects in the 2008 presidential elections look dim, unless something earth-shattering happens and reverses the trend. Meanwhile, the return of the Democratic Party can be expected to have a positive impact on the United States’ standing in the world. President Bush’s penchant for a hard line and confrontationist approach on issues such as the war on terror, security laws, immigration and even his own allies in Europe. It would be in America’s own interest if this militancy is tempered with moderation. What this holds for Pakistan time alone will tell.

No glory in arms exports

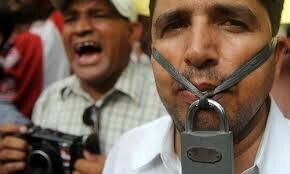

IT is easy to lose sight of priorities when reason is overshadowed by jingoism and narrow interpretations of national interest. The chairman of the Pakistan Ordnance Factories may be enthused but there is little to celebrate in the news that arms production and marketing may shortly receive a major boost. There would be greater reason to cheer if software exports had taken off, or if Pakistan were producing low-cost, life-saving medicines. Also worthy of applause would be self-sufficiency in basic food items and meaningful strides towards the goals of universal literacy and healthcare. In the absence of tangible achievement in areas that really matter, what is trumpeted instead are symbols of military might. Towering replicas of tanks, missiles and fighter jets, the usual props of states that fail their people, surround us to this day. These are poor substitutes for housing, schools and hospitals. Even though the generals insist that the country currently faces no external threat, defence expenditure continues to consume a major share of the country’s resources. It appears that we must remain in a constant state of over-readiness to take on our enemies, even at the cost of social and economic bankruptcy.

Among other instruments of death, Pakistan is proficient in the manufacture of anti-personnel landmines — weapons that do not discriminate between children and soldiers and continue to maim and kill civilians in areas that were conflict zones decades ago. It is estimated that landmines claim at least 15,000 to 20,000 new casualties every year. The country keeps company with Burma, China, India, Cuba, North and South Korea, the United States and Vietnam in the shrinking club of 15-odd countries that still produce anti-personnel landmines. Only 41 countries are yet to sign the Mine Ban Treaty of 1997 which came into effect in 1999. Pakistan is one of them, along with the likes of India, Israel and the US. No one can deny that the country’s armed forces have to maintain a basic level of defence. But there is no glory in being an exporter of weapons or entering an unwinnable arms race.

Playing with lives

THE lessons of past mistakes continue to elude our government agencies. On Sunday, seven children in Karachi’s Orangi Town received burn injuries while playing in an empty plot where a factory had been dumping inflammable chemicals. Luckily, all seven are now said to be out of danger. Not so fortunate, however, were many among the twenty-odd children who received horrific injuries in the Site area in March this year after coming into contact with highly toxic industrial waste. One boy died while several had their limbs amputated. That tragedy also resulted from chemicals being dumped in a vacant plot used as a playground by neighbourhood children. So corrosive was the material that it virtually ate away the feet and legs of the children who stepped in it. In December 2004, at least eight youngsters suffered burns from chemical waste while playing near their homes in a coastal village in Bin Qasim Town, Karachi. The guilty parties were believed to be factories located in the Landhi-Korangi export processing zone.

The Sindh Environmental Protection Agency sprang into action after Sunday’s accident, collecting samples and promising to issue notices to the factory responsible for the illegal dumping. While the effort to ascertain culpability is welcome, the Sindh EPA must realise that its role cannot be limited to after-the-event measures and the same is true of the provincial industries and environment ministries. It is their responsibility to ensure that such dumping does not occur in the first place. This can only be achieved through year-round and honest monitoring. It may also be useful to reconsider the maximum punishment laid down for such contraventions of the Pakistan Environmental Protection Act 1997. A one-million-rupee fine may deter small-scale manufacturers but is a pittance for big industrialists. An example has to be made of unscrupulous factory owners, and financial penalties alone may not suffice in such cases.

Iqbal and Muslim nationalism

ALLAMA Iqbal’s core contribution to Muslim regeneration lay in giving his people an idea, something to live and die for. In tandem, it also lay in fostering in them the moral fibre and the determination to realise that idea. That fostering was inspired by his soul-lifting verses that worked almost like magic. By the last decade of his hugely productive life, he had assumed the role of an ideologue, besides being the national poet.

ALLAMA Iqbal’s core contribution to Muslim regeneration lay in giving his people an idea, something to live and die for. In tandem, it also lay in fostering in them the moral fibre and the determination to realise that idea. That fostering was inspired by his soul-lifting verses that worked almost like magic. By the last decade of his hugely productive life, he had assumed the role of an ideologue, besides being the national poet.

Towards the intellectual and political emancipation of the Muslims Iqbal’s contribution was fourfold. Through the powerful medium of poetry, he had drawn the attention of the people to the depths of degradation to which they had fallen; he had diagnosed their ailments and the causes of their decline; he had warned them of the dire consequences if they failed to mend their ways in time. Above all, Iqbal had also outlined a destiny for Indian Muslims at a most critical juncture in their history.

In so doing, he proved himself to be a man of vision. An outstanding intellectual, who had the ability to analyse their situation in the context of their past history and current developments and gave serious thought to both their short-term and long-term problems. He envisioned for them a destiny which, while congruent with the Indo-Muslim ideological legacy, provided an answer to their current problems and predicaments.

Poet-Philosopher Iqbal spelled out his vision and delineated the contours of Muslim India’s destiny in his famous presidential address to the annual session of All India Muslim League in Allahabad in December, 1930. By far the most important of his various political pronouncements concerning Muslim destiny in India, this address was as significant as Jinnah’s presidential address to the League’s Lahore Session on March 23, 1940, which provided the background and the justification for the adoption of the Lahore Resolution (1940).

In his 1930 address, Iqbal, if only because of his wide-ranging scholarship, his deep insight into Muslim history (both in the subcontinent and elsewhere) and his close familiarity with the Muslim ethos, was able to attempt in a profound way the intellectual justification of Muslim nationhood, of a separate Muslim nationalism, and for the “centralisation of the most living portion of the Muslims of India” in a specified territory — “a consolidated North-West Indian Muslim State” in a truly federal state.

Iqbal justified Muslim India’s claim to nationhood on the basis of the “moral consciousness” engendered by the Muslims’ deep commitment to Islam, its ethics and ethos and its institutions. He argued, “Islam, regarded as an ethical ideal plus a certain kind of polity — by which expression I mean a social structure regulated by a legal system and animated by a specific ethical ideal — has been the chief formative factor in the life-history of the Muslims of India. It has furnished those basic emotions and loyalties which gradually unify scattered individuals and groups and finally transform them into a well-defined people, possessing a moral consciousness of their own.

“Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that India is perhaps the only country in the world where Islam, as a people-building force, has worked at its best. In India, as elsewhere, the structure of Islam as a society is almost entirely due to the working of Islam as a culture inspired by a specific ethical ideal. What I mean to say is that Muslim society, with its remarkable homogeneity and inner unity, has grown to be what it is, under the pressure of the laws and institutions associated with the culture of Islam.”

Clearly, Iqbal was “not despaired of Islam as a living force for freeing the outlook of man from its geographical limitations”. For one thing, he felt that “religion is a power of the utmost importance in the lives of individuals as well as States”. Above all, he believed that “Islam is itself Destiny and will not suffer a destiny” (emphasis added).

Despite all this, he could not possibly ignore what was happening to Islam and the Muslims in India and elsewhere. “True statesmanship”, he told his Allahabad audience, “cannot ignore facts, however unpleasant they may be. The only practical course is not to assume the existence of a state of things which does not exist, but to recognise facts as they are and to exploit them to our greatest advantage”.

Hence, Iqbal took due cognisance of the fact that in attempting to get rid of foreign domination, to withstand western designs as well as to rehabilitate themselves, the Muslim countries had unwittingly opted for nationalism and nationalist movements, that the national idea was racialising the outlook of Muslims everywhere, and that the growth of racial consciousness might as well mean “the growth of standards different from and even opposed to the standards of Islam”.

Iqbal recognised that the Muslim countries could organise themselves on a national — that is, territorial — lines, and yet be the chief decision-makers and masters in their own affairs for the simple reason that since they were predominantly in a majority in their own countries.

But the Muslims of India were differently situated. Although comprising some 70 million and constituting of the largest bloc of Muslims anywhere in the world except Indonesia, they were still a minority in the subcontinent, comprising only one-fourth of India’s total population. Hence their adoption of undiluted nationalism would undermine their distinct place in Indian’s body politic, depriving them of the opportunities of “free development”, unthwarted by the interference of the dominant community.

Since the people of India had refused to pay the price required for the formation of the kind of moral consciousness which, according to Renan, constitutes the essence of national feeling and nationhood, as evidenced by the failure of Akbar, Kabir and Nanak to capture the imagination of the Indian masses as well as the nobility, India at the moment could not be considered a “nation” in the western sense. On the other hand, since Islam had provided the Indian Muslims with a moral consciousness of their own, Iqbal argued, they were the only Indian people who could aptly be described as a “nation” in the modern sense of the word.

Having thus made out a cogent case for Muslim nationhood, Iqbal went on to suggest a viable solution to India’s communal problem: “a redistribution of British India” and territorial readjustment, which would yield a stable and largely homogeneous Muslim province in north-western India. It is in this context that he suggested the amalgamation of Punjab, the North-West Frontier Province, Sindh and Balochistan into a single state (or province), and the formation of a consolidated north-west Indian Muslim state. He also suggested the exclusion of Ambala Division and perhaps some of the non-Muslim dominant districts, with a view to making it less extensive and more Muslim in population.

Iqbal’s reasons in favour of his solution were unassailable. Since Indian nationalism was pro-Hindu and predominantly Hindu-oriented, the Muslims should adopt a separate “nationalism” of their own. Since the whole of India could not be won for Islam, if only because of the overwhelming Hindu majority, “the life of Islam as a cultural force” in India must be saved and salvaged by centralising it “in a specified territory”. This must be realised by setting up “a consolidated North-West Indian Muslim State”, comprising “the most living portion of the Muslims of India”.

It is also significant that Iqbal demanded “the creation of autonomous states” on the basis of “the unity of language, race, history, religion and identity of economic interests” “in the best interest of both India and Islam”.

Iqbal’s elucidation of this last point is important. “For India, it means security and peace resulting from an internal balance of power; for Islam, an opportunity to rid itself of the stamp that Arabian imperialism was forced to give it, to mobilise its laws, its education, its culture and to bring them into closer contact with its own original spirit and with the spirit of modern times.”

Thus, while the bases or attributes of nationalism such as language, race, history, identity of economic interests and viable territorial frontiers (and territorial unity) were sought to be incorporated among those of the “Pakistan” demand in 1940, religion was retained as the uniting factor and the consequences were to be spelled out in essentially Islamic terms. Thus were laid the intellectual foundations of Muslim nationalism in India.

The writer is a former founding director of the Quaid-i-Azam Academy and is currently a director of The Iqbal International Institute for Research, Education and Dialogue, Lahore. E-mail: smujahid107@hotmail.com

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.