THE RISE OF CRYPTOCURRENCY

Cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin have taken the world by storm, bypassing state regulators, providing privacy and unprecedented returns on investments as well as a new vision of financial markets. Despite all the hype, however, few people — especially in Pakistan — really know what’s going on behind the buzz. Eos offers a primer…

Bitcoin, the rogue digital currency, is a fixture in the news. Last week, the formal launch of the very first Bitcoin exchange-traded fund raked in investment worth 550 million dollars on just the first day alone. And Bitcoin prices hit an all-time high, crossing 66,000 dollars per Bitcoin.

Crypto-mania is surging in Pakistan too: we reportedly rank third globally, behind India and Vietnam, in crypto adoption metrics. Binance, a cryptocurrency exchange, is reportedly one of our top downloaded apps. And social media is abuzz with investment advice.

Bitcoin enthusiasts are also making a renewed push for crypto-friendly rules and regulations, with the Sindh High Court setting up a committee to look into the matter and to consider the legality of transacting cryptocurrencies.

What started as an underground experiment by a handful of programmers is now a trillion-dollar ecosystem. Bitcoin, valued at 1.2 trillion dollars, exceeds the market cap of Tesla and Facebook, and is significantly bigger than payment giants Mastercard, PayPal and Visa put together. In a recent rally, the combined cryptocurrencies universe reached a value of 2.2 trillion dollars, outpacing tech behemoth Apple — the world’s most valuable company.

There is now a multitude of cryptocurrencies, an entire constellation — a price-tracking website lists over 6,000 entries. While most of these, such as Litecoin and Dogecoin, are little more than Bitcoin copycats, there are also some truly dazzling innovative offerings. For instance, Ethereum goes beyond mere currency and provides a platform to create complex decentralised contracts and applications. Ripple is an efficient medium to send remittances and settle payments. Cardano tops the list of ‘green’ cryptocurrencies, with an energy footprint less than 0.001 percent of Bitcoin. Zcash and Monero incorporate privacy-enhancing technologies.

This ascent is breathtaking. It’s been little more than 10 years since a programmer operating under the enigmatic moniker of Satoshi Nakamoto first popped on to an online forum, recruited a handful of programmers and set out to build a revolutionary new digital payments system.

What started as an underground experiment by a handful of programmers is now a trillion-dollar ecosystem. Bitcoin, valued at 1.2 trillion dollars, exceeds the market cap of Tesla and Facebook, and is significantly bigger than payment giants Mastercard, PayPal and Visa put together.

No one has ever met him or spoken to him, all communication was via forum posts and emails, which ceased shortly after Bitcoin was launched. There has been considerable speculation as to his identity over the years. It is one of the biggest mysteries of this century — who is this unknown man?

Back then, early users were desperate for traction and were literally giving bitcoins away for free on the internet. Today Bitcoin is the best-performing asset class of the decade, with cumulative gains exceeding 20,000,000 percent, far outperforming the stock market index Nasdaq-100, which registered gains of a mere 541 percent. This is unprecedented and there is nothing like it. Small wonder then that our collective fascination with all things Bitcoin, cryptocurrency and blockchain continues to grow in leaps and bounds.

Despite all this hype, few people really know what’s going on behind the buzz. What is Bitcoin? How does it really work? Why was it created? What is all the fuss about? And what does the future hold?

We try to explain.

CRYPTO IN A NUTSHELL

I teach an MS-level course on cryptocurrencies and I usually start the very first class with a question: what is the real difference between Bitcoin and our traditional everyday money?

Bitcoin is digital, students mostly say. Yes, I respond, but so are Mastercard, Visa and PayPal. Bitcoin only exists online, is the second most common response. True, but in reality, most of the world’s money supply is digital. Only an estimated eight percent of the world’s money really exists as hard physical cash.

Another typical refrain: there’s nothing behind Bitcoin, it is not backed by gold or reserves. Yes, also true, but no major currency today is backed by gold or tangible reserves. Bitcoin is decentralised, some say. Yes, but what does that really mean? How does that make Bitcoin uniquely different from every currency in the world?

The simple difference is this: we derive our trust and confidence in existing currencies — and in the larger financial ecosystem — as a result of government oversight and regulation. If some rogue party starts printing currency notes or hacking into banking databases, reversing transactions or inflating account balances, we expect the government will use its full might to track them down and lock them away for a very long time.

We expect the government to carefully manage the money supply to cope with inflation and economic stress. In short, our traditional currencies are rigorously policed by government writ.

In stark contrast, there is no government stick behind cryptocurrencies. Bitcoin uses cryptography — the mathematical techniques used to secure information — to ensure that everyone follows the rules. Users manage their own coins. The network collectively validates and processes all transactions. The money supply is controlled by an algorithm and cannot be manipulated. Government and banks have been cut out of the equation entirely. In this sense, Bitcoin is far more than just a novel technology — it is an entirely different paradigm for money.

REINVENTING MONEY

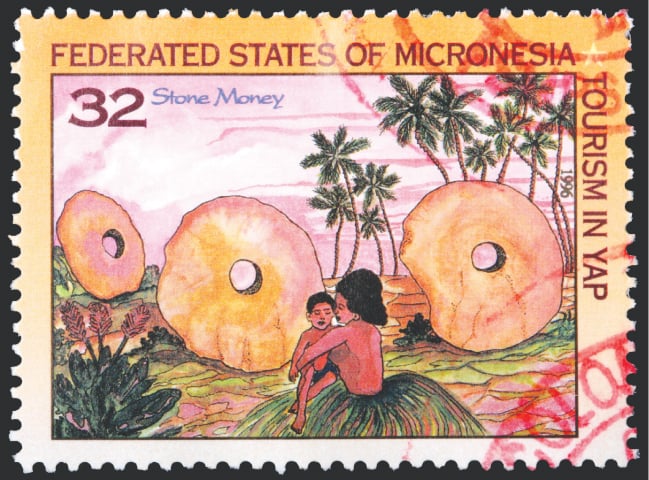

To get a grip on this paradigm, let’s look at a real-world example. Some 500 years ago, on a small island group called Yap in the Pacific Ocean, the natives invented a fascinating economic system. As currency they used huge carved stone disks called rai stones. Taller than a man and weighing more than a car, these stones were too big to carry around and lay scattered around the island.

Transactions followed a simple protocol: if two tribesmen wanted to transact, they would assemble the entire tribe and formally announce transfer of ownership of a rai stone from one party to the other. The tribe would note the change and confirm the transfer. If a tribesman were to transfer a stone that did not belong to him or one that he had already given to someone else, the tribe would not permit it.

Satoshi Nakamoto’s genius lies in resurrecting this economic paradigm in the digital domain. This is no mean feat. Nakamoto drew together cutting-edge innovations in computer science and information security to reinvent the notion of ownership.

This is, in effect, a decentralised system. There is no bank or central authority which maintains records and processes transactions; it is the collective effort of a community of peers. Every peer individually verifies each transaction. Any disputes that arise — due to failing memories or absent witnesses, etc — are settled by a majority consensus. If an earthquake suddenly swallowed up half the tribe, the survivors could still process transactions, business would go on. In one case, a rai stone sank in the sea. Witnesses told the tribe and they made a note of its location. And so it remained part of the money supply and continued to be used in transactions.

We are now in a position to rethink our notion of money. Money doesn’t have to be precious metals or government-issued scraps of paper that we carry in our pockets. As Yap demonstrates, money can simply be public information about ownership of assets, subject to change with every transaction and is ratified by the community. Who needs banks and politicians?

LET’S GET TECHNICAL

Satoshi Nakamoto’s genius lies in resurrecting this economic paradigm in the digital domain. This is no mean feat. Nakamoto drew together cutting-edge innovations in computer science and information security to reinvent the notion of ownership. In the digital domain, Bitcoin currency units — referred to as bitcoins (with a small b) — are the equivalent of rai stones and our Yap tribesmen are now replaced by anonymous faceless internet users who run the Bitcoin software. These users are interconnected with each other, forming a large computer network — simulating the tribal congregation of Yap — where all peers individually witness, record and validate transactions in real-time.

Transacting parties possess a pair of cryptographic credentials. First, a ‘Bitcoin address’ — a unique identifier, which is essentially the equivalent of a user’s bank account number. When someone wants to send me bitcoins, I give them my Bitcoin address so they know where to send them.

The second credential, a corresponding ‘private key’, enables the owner of a Bitcoin address to spend the coins associated with that address. This key gives him the ability to create a digital signature on a Bitcoin transaction, pretty much the cryptographic equivalent of a physical signature on a cheque. A digital signature can be easily verified by anyone who looks at it but it cannot be forged unless an attacker were to somehow access the user’s private key. It is essential therefore that the user keeps this private key — as its name indicates — absolutely private.

Let’s assume two parties, Azra and Bilal, transact. Azra creates a transaction, essentially a statement noting that five bitcoins are to be moved from Azra’s Bitcoin address to Bilal’s Bitcoin address. Azra authorises the transaction using her digital signature. The transaction also includes a reference number to a prior transaction where Azra has received coins — in essence, Azra has to provide proof in her transaction that she actually possesses the coins that she is now spending. She cannot spend coins belonging to someone else or create coins out of thin air. Just like rai stones, every bitcoin has a lineage. Every Bitcoin transaction refers to a prior transaction, so on and so forth, forming a long thread all the way back to special coin-generation events.

Azra then circulates her transaction on the Bitcoin network, where all peers can see it and verify that the signature is genuine and the transaction is valid.

In stark contrast, there is no government stick behind cryptocurrencies. Bitcoin uses cryptography — the mathematical techniques used to secure information — to ensure that everyone follows the rules. Users manage their own coins. The network collectively validates and processes all transactions.

We are not out of the woods yet. Azra can still ‘double-spend’, meaning that she can easily create another perfectly legitimate transaction, sending those very same coins she sent to Bilal to someone else. This was the major challenge encountered in earlier attempts at digital currencies.

In the real world, every physical coin or currency note is unique and can only be spent once. But on computers, as we are well aware, there is no limit to the number of times any file or object may be replicated. It is simply a matter of selecting an item and invoking COPY and PASTE (CTRL+C followed by CTRL+V on the keyboard). This is where Bitcoin makes a fundamental contribution, giving us for the very first time — to quote Eric Schmidt, legendary ex-CEO of Google — “the ability to create something that is not duplicable in the digital world.”

If we have two conflicting transactions, obviously only one of them can be allowed. We need an authoritative way to determine which transaction makes the cut. In the real world, this is the job of central banks and clearing houses — they collect, validate and finalise transactions, toss out conflicting ones and prepare a single detailed record, an authoritative history of financial activity. But a central bank is anathema to Bitcoin’s philosophy of decentralisation.

Nakamoto’s eureka moment: instead of having a dedicated central bank to clear transactions, why not pick network peers randomly to act as the central bank for very short time intervals? Instead of a single entity maintaining an authoritative financial history of all transactions, let’s make it a group effort, with different authors at different points in time.

If the peer selection process is truly random, it cannot be hijacked by a dishonest party. If the record is shared publicly, the community can police the transaction record as well and collectively reject inputs by malicious peers who try to authorise double-spends or insert invalid transactions in the record. We can even make the history ‘immutable’ by deploying cryptographic techniques such that new information can be added to the records, but peers cannot manipulate or change prior transaction records.

Bitcoin’s core founding principle is a deep and abiding distrust of banks and governments.

We refer to this as mining. Every 10 minutes, several Bitcoin peers — referred to as miners — participate in a lottery, where they compete to solve cryptographic puzzles. The winner gets to finalise transactions for the period and is rewarded with new bitcoins. The finalised transactions for the period form a block, which is circulated over the network, along with proof that the miner won the lottery. Every peer individually checks the proof, confirms that the included transactions are valid and then stores the block, linking it with previous blocks, forming a long chain.

This is the famous much-hyped blockchain, an immutable and authoritative record — a ledger of sorts — of all transactions that have been successfully processed by the network. Every new incoming transaction is verified against this ledger. The process is efficient and automated, and costs a fraction of what it would if transactions were manually processed. Bitcoin users can even insert complex scripts into their transactions to craft complicated contracts that do not rely on financial intermediaries for execution.

Hopefully this high-level description gives a sense of the immense scope and depth of the Bitcoin project, what Bill Gates describes as a “techno tour de force.” This is only half the story though. Moving beyond the technology, we find Bitcoin’s economic vision, which is much less known, hardly ever discussed, but every bit as fascinating and revolutionary.

Nakamoto is perhaps the only individual nominated not just for the Turing award, the Nobel prize for computing, but also for the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. The latter nomination was promptly dismissed on technical grounds — apparently the prize is not awarded to anonymous parties. But there is no denying that Bitcoin makes a profound contribution to economics: it enables direct financial interactions without trusted intermediaries.

Bitcoin’s core founding principle is a deep and abiding distrust of banks and governments. We need to ask here: where does this pronounced apathy come from?

BITCOIN — SLAYER OF BANKS

There is a common sentiment, going back centuries, that the financier class — the moneylenders, bankers and speculators — are an unmitigated evil responsible for quite a bit of misery in the world. Aristotle described usury as the “unnatural breeding of money from money.” Traditional cultures regard it as a mortal sin. In Dante’s Inferno, moneylenders are relegated to a pit in hell below violent murderers and blasphemers. These sentiments became more pronounced with the rise of organised banking. US founding father Thomas Jefferson considered banking institutions “a blot” on the constitution, more dangerous than “standing armies.” Karl Marx pronounced them “the most effective means of driving capitalist production beyond its own limits” and “one of the most effective vehicles of crises and swindle.”

At the launching ceremony of the State Bank of Pakistan in 1948, Quaid-e-Azam called for an overhaul of the system itself. “The economic system of the West has created almost insoluble problems for humanity,” the Quaid said. “And, to many of us, it appears that only a miracle can save it from the disaster that is now facing the world. It has failed to do justice between man and man and to eradicate friction from the international field. On the contrary, it was largely responsible for the two world wars in the last half-century.”

This line of thought can be unnerving for those who encounter it for the first time, it reads like the ultimate conspiracy theory, but it’s no surprise for those who read the business papers. Banks are typically at the forefront of speculative bubbles which wreak havoc on society. We saw this for ourselves first-hand, in raw and gory detail, over the last two decades.

For instance, large investment banks were key players in the catastrophic global food bubble of 2005-2008. Banks such as Goldman Sachs, Barclays and Morgan Stanley launched commodity indexes that financialised food markets. This sudden influx of capital and rampant speculation pushed food prices to 30-year highs, pushing over a hundred million people into poverty, sparking mass riots in several countries and triggering the Arab Spring. The UN World Food Programme described it as a “silent tsunami of hunger.” One newspaper referred to it as “[t]he real hunger games.” The big banks netted millions in profits and they got away with it.

The Great Recession of 2007 featured similar egregious behaviour on the part of banks: dubious lending policies and a distinct lack of regulation created colossal unsustainable bubbles which burst with a sound heard around the world.

This is vital context to Nakamoto’s own thought process. In his words: “The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve. We have to trust them with our privacy, trust them not to let identity thieves drain our accounts. Their massive overhead costs make micropayments impossible.”

A FAMILIAR VISION

When Bitcoin launched in the troubled days of the Great Recession of 2007-2009, Nakamoto embedded a text message in the very first block, a headline from The Times, which further reinforces his stance: “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

Nakamoto’s vision — to cut banks and governments out of the equation — hearkens back to the Austrian school of economics, which features prominent contrarians Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and Murray Rothbard. Austrian economists are strong proponents of the invisible hand of markets and staunch critics of both Keynesianism and Marxism. They contend that manipulation of interest rates and credit inflation by banks is the real cause of business cycles, the constant painful boom and bust events.

Nakamoto never referenced this school of thought in his posts, but the parallels are striking. For instance, Rothbard equates modern central banks with counterfeiters. Nobel-winner Hayek wrote: “When one studies the history of money one cannot help wondering why people should have put up for so long with governments exercising an exclusive power over 2,000 years that was regularly used to exploit and defraud them.”

In an interview in 1984, Hayek went one step further: “I don’t believe we shall ever have good money again before we take the thing out of the hands of government,” he said, his words taking on a prophetic ring. “We can’t take it violently out of the hands of government. All we can do is, by some sly roundabout way, introduce something they can’t stop.”

GOVERNMENTS VS ALGORITHMS

Cryptocurrency trends are best understood within this broader picture. At first governments and banks took little note of Bitcoin, it was too small, too radical, hard to understand and easily ignored. Regional economic uncertainty has been a significant factor driving up Bitcoin prices. Examples include Venezuela and Turkey where cryptocurrency adoption has skyrocketed in recent years amid economic crisis and massive inflation.

Cryptocurrencies are also effective at evading banking channels and regulatory scrutiny. At the global level, Venezuela and Iran are circumventing US sanctions by using Bitcoin for trade payments. At the individual level, cryptocurrencies are an easy way to bypass exchange and capital controls. They are a natural fit for tax evasion and money laundering, to paraphrase Barack Obama, ‘like having a Swiss bank account in your pocket.’

One investigation found that in 2020 more than 50 billion dollars’ worth of cryptocurrency assets shifted from China-based addresses to overseas. The IMF warns that the surging popularity of cryptocurrencies could aid capital flight and undermine financial stability in developing countries. Growing recognition of these trends has led several countries, notably Turkey and China, to ban these “super sovereign” currencies.

On the other hand, some countries welcome Bitcoin as a desirable alternative to legacy financial infrastructures and to increase inclusiveness. El Salvador recently legalised Bitcoin to give expats a better way to transfer remittances. Last year, remittances worth around six billion dollars flowed into El Salvador, accounting for 23 percent of the country’s GDP. With Bitcoin, the government estimates savings of around 400 million dollars, which go into fees for money transfer services such as Western Union.

Moreover, PricewaterhouseCooper (PwC) reports, that some 60 governments are currently developing their own digital currencies. Most of these are blockchain-based efforts but, unlike Bitcoin, are heavily centralised, falling under the purview of central banks who will likely control the mining process. The trade-off here is clear: Bitcoin’s efficiency minus the freedom.

At the launching ceremony of the State Bank of Pakistan in 1948, Quaid-e-Azam called for an overhaul of the system itself. “The economic system of the West has created almost insoluble problems for humanity,” the Quaid said.

For privacy-conscious citizens, this is a scenario right out of George Orwell’s 1984. Unlike the case with physical cash, with central-bank digital currencies, the government gets a window into every transaction a citizen makes, along with the power to directly control transactions and blacklist users. China leads this effort. China’s digital yuan has already been trialled in 11 cities, with over 1.32 million transactions, amounting to 5.4 billion dollars. It is due to launch at the Beijing Winter Olympics early next year.

The investor community has fully jumped on board the Bitcoin bandwagon, which is only natural, considering its stratospheric price gains. Some of the world’s biggest investors are hoarding Bitcoin as a hedge against inflation and economic calamity, a role traditionally reserved for precious metals and government bonds.

Bitcoin is the new digital gold, a safe haven asset for the new generation. And then we have the vast majority of investors, the speculators, actively playing this market, surfers who ride the wave when prices rise and then cash out during the dips.

This is a very different road from Nakamoto’s original vision — of a liberated people using Bitcoin like real money — for paying rent and buying groceries. Moreover, we are also discovering that Bitcoin has lots of problems.

THE NEGATIVES

The first and foremost argument against using Bitcoin as money is its extreme price volatility. Bitcoin is a purely digital commodity without government backing or any clear stabilising factor, and its price is at the mercy of speculators and social media influencers. Over the last few months, Elon Musk’s tweets alone have sent Bitcoin and Dogecoin prices soaring and crashing alternately, by as much as 15 percent.

Second, using Bitcoin requires a level of technical sophistication that most people simply don’t have. We struggle with website logins and WiFi passwords, let alone Bitcoin addresses and private keys. Add to this the fact that there is an epidemic of new computer viruses and sophisticated malware, which infect users’ computers and can steal their Bitcoin credentials.

A popular solution to technical headaches is to use a cryptocurrency exchange, an online service which manages coins and payments on behalf of users — much like using internet banking. But exchanges are routinely hacked, losing millions of dollars’ worth of users’ coins.

Overall there is no grand vision for cryptocurrencies in Pakistan. Our mainstream discourse is unfortunately dominated by the profit motive — and this is perhaps the least interesting aspect of the cryptocurrency conversation.

And this leads us to one of the biggest problems with cryptocurrencies. In case of fraud or theft, our banks can reverse transactions, coordinate to track down criminals and sanction illegal businesses. But if someone steals my bitcoins, there is nothing I can do about it. There is no bank or regulator to turn to. The government cannot help.

Centralisation certainly has its perks.

Bitcoin also has fundamental design limitations: it can only process about seven transactions per second, far less than processors such as Visa which routinely handle about 1,700 transactions per second. Bitcoin also has a huge energy footprint: mining consumes an estimated 0.55 percent of the global electricity supply, similar to the energy-profile of small countries such as Malaysia or Sweden.

More disturbing though are brand new problems that we never expected. Bitcoin has given rise to dark markets — black markets and bazaars operating on untraceable online networks — which deal in drugs, weapons, pornography and other illicit goods.

We also now have hackers disrupting computer operations and extorting citizens, companies and governments for money. Readers may recall K-Electric suffered a ransomware attack last year. These criminal activities are collectively racking up billions of dollars in profits.

BITCOIN AND PAKISTAN: THE BIGGER PICTURE

The State Bank of Pakistan has prohibited banks and payment processors from dealing in cryptocurrencies. This is not technically a ban on individual usage but the boundaries are vague. The FIA actively investigates cryptocurrency use among citizens to the point where the Sindh High Court has had to restrain them from harassment. Matters are further complicated by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which has asked the government to better regulate cryptocurrencies.

The short-term challenge for our regulators is to identify that fine point between profit, consumer protection and criminal activity. Users are keen to benefit from the global cryptocurrency boom but we need to protect them from fraud and prevent capital flight, money laundering and tax evasion. This is difficult and there is no readily available model for this. The best we can do is study policies from countries with similar aims, such as Brazil and El Salvador.

There are plans to set up Bitcoin-mining operations in KPK. One only hopes such ideas are backed by rigorous cost-benefit analyses. In several cases, it may be more profitable to simply buy and hold bitcoins in the long run than to set up expensive infrastructure to mine them from scratch. And how do the environmental costs square up against our much-hyped green credentials?

Overall there is no grand vision for cryptocurrencies in Pakistan. Our mainstream discourse is unfortunately dominated by the profit motive — and this is perhaps the least interesting aspect of the cryptocurrency conversation. At some point we will need to set aside the get-rich-quick mentality and ask the hard questions.

Bitcoin is a new paradigm, perhaps even the start of a new social order. As Nakamoto has pointed out, banks and governments fail us often. But Bitcoin does not fix these institutions, it simply builds around them. This seductive instinct — to innovate our way around pressing social problems instead of confronting them head-on — hurtles us ever deeper toward an algorithm-driven world. Sci-fi ideas such as Bitcoin are brilliant on paper, but it is very much an open question how they translate into the real world.

Would we want to normalise a world where we are in open conflict with our overlords? A world where trust, the so-called ‘glue of life’, the foundational principle of human relationships, is negotiated by algorithms?

A society where no one trusts anyone is a society of loners, a dystopia, a desolate landscape plucked out of Mad Max or Blade Runner.

These questions are not for technologists or economists; they are a communal concern. These are the things we need to consider as we chart our own way in this brave new world.

Header illustration by Radia Durrani

The writer teaches at NUST and has a strong track record of research on cryptocurrencies and information security. He can be reached at taha.ali@gmail.com

Published in Dawn, EOS, October 31st, 2021