hen the water first came, panic rippled through the valley.

Up until then, most of the villagers had refused to leave. In a jirga held in one village, the elders had all lined up and one by one, with a Quran held over each of their heads, had solemnly sworn that they would stay.

Helicopters had hovered over the villagers' homes, dropping down flyers that urged them to evacuate, and despairing officials visited the valley, issuing exhortations first and ultimatums later. Many of the villagers didn't think there would be any water, though. Rumour had it that what the government really wanted to do was raze down their homes and set up a string of factories instead.

So, when water started swirling across their fields and orcp-0s and into their homes, the panicked villagers found themselves faced with a choice that could only be described as Hobsonian — that is, no choice at all. Some grabbed whatever was in sight and ran towards the mountains. Others clambered on to trees and waited, watching their belongings float by: Cooking utensils and crockery; bedclothes and a bridal trousseau. Roofs fell down – it had started to rain – and as the water on the ground surged, they watched their goats and cows float away. Some were stung by snakes — the water brought with it snakes, they said, snakes that writhed like "ropes".

The villagers left eventually. Some made their way to townships that had been set up for them; others went to lay claim to land that they had been promised in Sindh and Punjab, entering, more often than not, abrasive legal battles with provincial governments and qabza groups. Meanwhile, water continued to fill up their valley.

It was, the newspapers said, the start of a grand new era.

"The mighty Indus has been tamed!" exclaimed one headline. "The story of Tarbela is the story of mighty Indus: unleashing its forces to resist man's attempts to harness it, and the young nation's resolve to tame the river for the services of mankind."

N

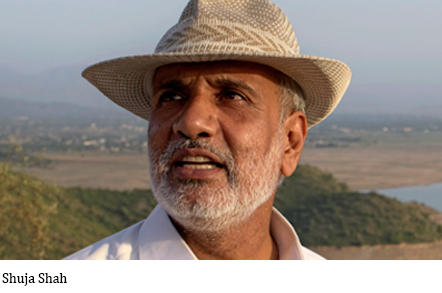

early four decades later, Shuja Shah stands at the edge of the 250 square kilometre lake that forms the reservoir of the world's largest earth-filled dam and hooks his shoulders into a half-shrug. The glassy surface of the lake gives little indication that an entire world – 196,000 people, 120 villages – once existed underneath.

"I guess these things happen in third world countries," he says.

Shah's village was situated on a slight altitude so when the waters of the Indus were first diverted for the dam, it wasn't flooded — as a boy, he watched with a mix of fascination and horror the water entering the villages below. The creation of the lake, however, cut his village off from the adjoining areas; the government promised a road but, for a long time, there was none. In emergencies – sudden illness, a complication during childbirth – the villagers' best bet tended to be a boat with an engine.

In the months when the water level recedes in the reservoir, the villagers return to the valley to visit the graves of their ancestors. Once, on one such visit, a herdsman saw the rock on which he would sit and play his flute; an old man now, he clung to it and cried. Many myths came to an end with the creation of the dam, says Shah — the villagers used to believe that the Indus was at least seven times as deep as the length of rope used in a charpoy and that beneath its waters, embedded in its bed, ran a stream of heavenly milk. Other things have become mere memories.

"You could hear the river each night," says Shah. "It would emit this dull roar."

He tries to recreate the sound now, with his voice: shshhh-shh-ssshsh. He laughs self-consciously when he fails. The vast pool of water before him remains impassive, unperturbed, and, looking down at it, Shah falls silent too. Later, he tries to explain what the dam had done to the villages and the villagers. Imagine that you are playing an instrument, he says, imagine that there is music. Suddenly someone snatches the instrument from your hand, throws it to the ground and stomps on it, then walks away. The music stops, the crushed instrument lies at your feet and in the ensuing silence, all you can do is wonder: What just happened?

ivers traverse both history and geography; they flow through time as well as space. Rising in Tibet, running west through India, then south across what is now Pakistan, the Indus has been flowing for millennia. Silent observer, sometimes partaker, of history, it has nourished some of the world's earliest cities; it has intimidated explorers, exasperated engineers and enthralled poets and peasants alike. The Buddha, it is said, lived beside it in a previous incarnation; the founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak, found enlightenment whilst bathing in one of its tributaries. The Atharvaveda, one of the world's oldest religious texts, refers to it as saaransh, everflowing.

The Indus of the imagination – although, of course, it is older than human imagination itself – is an Indus that flows un-dammed and undimmed. The Indus that we know today is a different river, however: It dies an ignominious death in the plains of Sindh, more serf than strong brown god. If rivers are indeed the ultimate metaphors of existence, if we see in them what we see in ourselves, what is this diminishing river telling us about ourselves?

n odd thing came to pass last August.

By then, the monsoons had set in and the Indus and its tributaries were in spate; barrages and dams were on high alert and flood managers were maintaining a constant vigil by the water. This in itself was not unusual — the Indus, after all, is a vast and winding river and threats could manifest from many directions: From the sky in the form of heavy rains, from the north in the form of excess glacial meltwater, from the west via hill torrents and from the east in the form of India releasing water into the eastern tributaries under Indian control. As parts of Punjab and the upper reaches of Sindh became inundated, forcing people out of their homes, apprehensions increased. No one, it is safe to say, wished to relive the floods of three years ago.

But further south, a few hundred farmers were out on the streets for a different reason — they were protesting the lack of water. On August 19, growers from the command area of Imam Wah Jagir, a small canal, blocked the Badin-Karachi national highway, suspending traffic for more than three hours. They were accusing irrigation officials of diverting canal water illegally into 38 pipes unlawfully installed to irrigate the lands of the influential landowners.

The flood coinciding with the protests captured the paradox of Pakistan's water woes: Too much water and too little water — but more worryingly, an inability to manage water. As an illustration of the ironies that abound in the water sector, it was perhaps surpassed only by the story of the ill-fated (and now-defunct) Karachi Port Trust Fountain, a 320-million-rupee lighted harbour structure, the third tallest of its kind in the world, which spewed seawater hundreds of feet into the air and that the then federal minister for ports and shipping described as a gift by the government to the poor of the country because "they cannot afford to visit Switzerland for rest and recreation". At the same time when this monument to profligacy was being built and inaugurated, several million gallons Karachi's water supply were lost to leakage, some hundred million gallons of raw sewage oozed into the sea and many neighbourhoods across the city failed to secure access to clean drinking water — every single day.

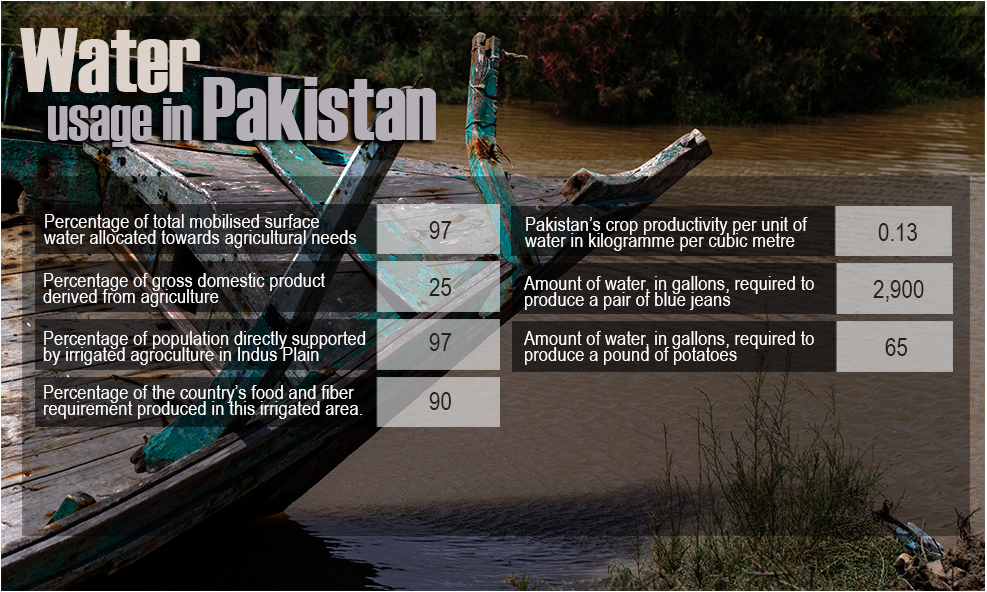

These anomalies are cause for great concern, more so now than in the past. In July 2013, a report released by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) pronounced Pakistan on the verge of being classified as water-scarce, with a storage capacity of only 30 days as against the recommended 1000 days for countries with similar climates. (It goes without saying, however, that one potential financier of the storage structures recommended by the report would be the ADB itself.)

A few years earlier, in 2010, a study published by the Water and Power Development Authority (Wapda) revealed that the country's per capita water availability had dwindled 406 per cent between 1951 and 2010 -- from 5,260 cubic meters to 1,038 cubic meters in 2010, only marginally above the 1,000 cubic meters per person threshold that is the global criteria. Since then it has dipped below that threshold.

"We are on the verge of a life-and-death situation," proclaimed Khwaja Muhammad Asif, federal minister for water and power, last October, warning that Pakistan could face a severe water shortage in the next 10 to 15 years. By the year 2035, added the federal minister for science and technology Zahid Hamid, the country may no longer have water reserves in the shape of glaciers. (According to a detailed regional study carried out by Dutch scientists at the University of Utrecht, however, while the Baltoro glacier that drains into the Indus will retreat drastically this century, losing roughly half its volume due to predicted global warming, water users will not experience scarcity, in part because the extra meltwater flowing into the Indus will help meet rising demands.)

Whether there is too much of it or too little, water requires managing. Wapda's grand water strategy, titled Vision 2025, calls for the construction of several dozen new large water projects, including five dams and three "mega-canals". But a growing chorus of voices has begun advocating the idea that this vision of ‘concrete' progress may not be quite so concrete after all. In 2009, a report by the Wilson Center titled, Running on Empty: Pakistan's Water Crisis, made the polite recommendation that "bigger is not always better", a gentle jibe at the country's fetish for grand projects a la the port fountain in Karachi. (Merely repairing and maintaining Pakistan's leaky canal system, argued water expert Simi Kamal in the report, would free up nearly 10 times more water than the quantity projected to be generated by the Diamer-Bhasha dam).

Since the 2010-2011 floods, the debate has become even more heated. One side argues that the presence of more storage dams could have mitigated the effects of the floods and that the existing ones served precisely this purpose — that, had there been no Tarbela Dam, as Shamsul Mulk, former Chairman of Wapda argues, Sukkur barrage downstream would have been washed away. On the other hand, critics of the ‘technocentric' approach to development argue that there normally isn't enough water to fill our dams – as it is, the Indus doesn't even reach the sea anymore – and neither is there any money for investment in big dams, let alone for keeping them operational and well-maintained.

Also emerging is another group of voices: People on the ground, such as Shuja Shah, who have directly experienced development in its current definition and who, finding themselves falling through the cracks, are beginning to express alarm at the redistributive effects of river engineering.

The debate is noisy and heated, mostly technical and often personal: The fight, after all, is over water, and water is essential to life. But one question that demands an urgent answer is this:

The Indus was once a river so vast that locals referred to it saagar, a sea. Local appellations in the river's uppers reaches still pay homage to its might: The Tibetans call it Sengo Tsampo or the Lion River, the people of Baltistan once called it Gemtsuh, the Great Flood and Pakhtuns refer to it as Abbaseen, the Father of Rivers.

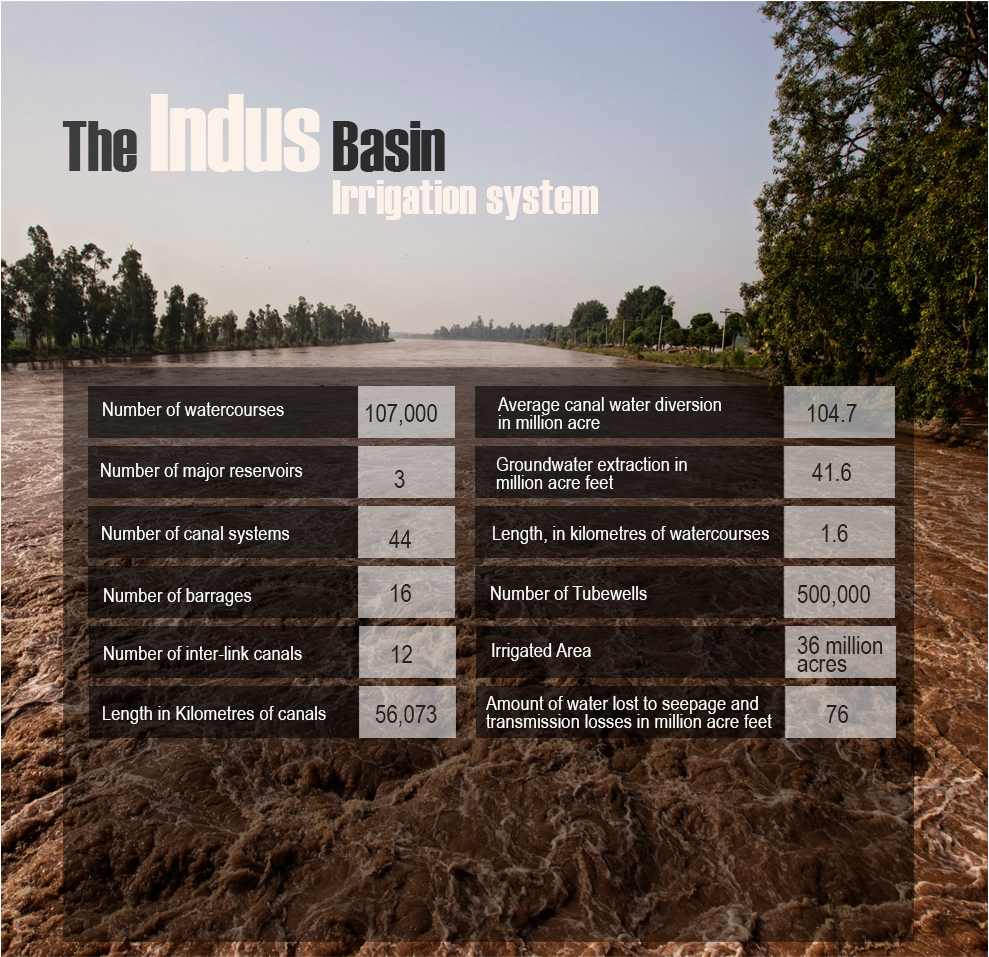

In terms of sheer quantity of water, the Indus remains one of the world's major rivers and the canals that extend from it, regulating and carrying this water to the farmland, form what the World Commission on Dams referred to as the world's "largest integrated, contiguous irrigated system". A river this size and a system this complex naturally requires attention: Consequently, there are 10 public sector institutions, 28 national level organisations and 19 academic and research centers that deal with the water sector in Pakistan.

Given that thousands of engineers and scientists, bureaucrats and politicians, activists and academics are watching over our water, how is it that we still find ourselves swinging wildly between the deluge and the water dying in channels much before reaching the fields?

ushtaq Gaadi, a teacher of anthropology at the Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, exudes the sense of a man consciously conserving his energy, perhaps for the battles ahead. He is a self-professed maverick — "I don't care if people think I'm stupid," he shrugs at a later point. "It takes the burden of heroism away from me". And, in keeping with this maverick streak, he nurses a deep mistrust of the current system of canal irrigation: "Where I come from," he says, "we say that a neher (canal) is actually a nahar (wolf)."

Where he comes from is Taunsa, a tehsil of Dera Ghazi Khan district in what people in Lahore and Islamabad call southern Punjab, or south Punjab, but what in local parlance is the Seraiki wasaib or the Seraiki region. The area fared badly in the 2010 floods. Where I am speaking to Gaadi is Islamabad, where policies were made that (some argue) exacerbated the impact of those floods. Gaadi believes that the rehabilitation of Taunsa Barrage, just prior to the floods, was responsible for much of the devastation in his region.

But first, he has a question for me. "What makes you interested in water issues?" he enquires. Journalistic curiosity aside, I tell him, my family's history was partially linked to water and its availability. When the Sukkur Barrage was built by the British in 1932, the first major waterworks project on the Indus, large tracts of land in Sindh suddenly became available for cultivation. My great-grandfather had been one of the growers who migrated from central Punjab to the south of Sindh to introduce cotton cultivation in the region. The tale of how he roamed the province on camelback is now part of family lore, I add with a laugh.

I offer this story for a reason, half-intending for it to serve as an entry pass into the seemingly exclusive club of water activists, a group where urban dwellers usually have little business of belonging. As it turns out, I may as well have hung a scarlet letter around my neck. Recognition flickered across Gaadi's face. "So you're one of the beneficiaries of the system, then," he says. I pause and, choosing my words carefully, reply that while I hadn't really thought about it that way, his observation probably isn't entirely untrue.

Gaadi nods and our conversation returns to the vagaries of water, its availability or otherwise — but a vague sense of indictment seems to hang in the air, in my mind at least, as does a subsequent feeling of unease. That water is a political issue in Pakistan, perhaps more so than any other natural resource, is not cause for surprise, and neither is the fact that debates surrounding it inevitably tend to take place within the framework of ‘us-versus-them'. What is disconcerting, however, is the realisation of just how deep the existing fissures are.

N

owhere perhaps are the lines (and swords) as clearly drawn as around one as-yet-unconstructed dam and nothing, it seems, is a better litmus test for one's ideas on nationhood and progress than the question of whether or not it should be built. In the public imagination, the proposed Kalabagh Dam has become many things: An answer, an excuse, a conspiracy against the federation.

More crucially, it is a mirror. The road from Islamabad to Mianwali, the district where the town of Kalabagh is located, is a difficult one: The landscape is sparsely populated and it undulates wildly. After several hours, our driver, a naturally nervous man whose anxiety seemed to mount as distance from the city increased, brings the car to a halt. "We can't go any further," he says firmly. "The area ahead is dominated by the Khattaks. They are extremely dangerous." Gaadi, who has been lost in his own thoughts thus far, suddenly looks up and at the driver, his inner anthropologist alerted. "It's true," he agrees, completely deadpan. "They're a terrible people."

The driver's eyes brighten up at this apparent affirmation. "So I should turn back, yes?" Gaadi shakes his head gravely. "No. Say a little prayer and carry on, saeen." The driver tries again. "The thing is, you can't trust a Pathan. He will stab you in the back. He will go back on his word."

There is a hierarchy, the driver goers on to explain, of people who must not be trusted: Poised at the very top of this pyramid is the flighty Pathan. ("Don't call them Pathans," whispers Gaadi. "It angers them. Call them Pakhtun.") Tied for second place were the Baloch and the Sindhis, continued the driver, himself a Kashmiri resident in Islamabad.

"And what are your thoughts on the Punjabis?" inquires Gaadi, with the air of a scientist scrutinising his subject. The driver thinks for a while. "A Punjabi might go back on his word. But he is definitely less likely to do so. He'll stick with his word for a while at least."

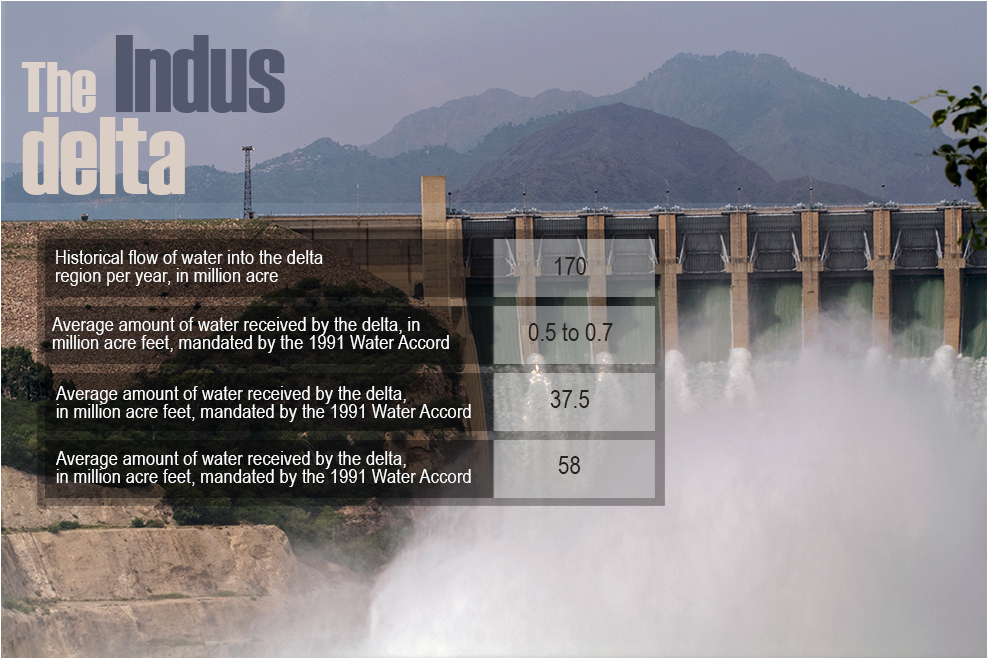

The deserted dam site, located upstream of the historic town of Kalabagh – the site of many invasions of India from the northwest, as testify its narrow, low-slung covered streets built to stop the attacking horsemen from entering the town -- and roughly a kilometer south of where the startlingly red waters of the Kabul river drain into the Indus, has become a monument to precisely such provincial and ethnic mistrust //remove the bold text//. There are technical concerns: Some within Khyber Pakhtunkhwa fear that the dam could trigger extensive backwater flooding, similar to the historic flood of 1929 that submerged the Grand Trunk Road from Khairabad to Nowshera and from Nowshera to Pabbi; that it might lead to waterlogging and salinity in the surrounding plains of Mardan, Pabbi and Swabi; that it could affect the operation of the existing Mardan Salinity Control and Reclamation Project (Scarp); and that it would submerge fertile land and displace, according to the 1998 census estimate, roughly 108,101 people. Sindh doubts whether there is enough water: Storing 6.1 million acre feet at Kalabagh will, it argues, reduce water flowing into Sindh province, affecting cultivation in the riverine areas (flood irrigated areas, known locally as sailaba), mangrove forests and shrimp production in the delta and adversely affect the Indus estuary, which has already experienced sea intrusion of up to 225 kilometers. Moreover, there is the fear that canals to be built along with the dam may divert more water to Punjab than the province's allocated share.

But what it boils down to, in the end, is trust – indeed, lack thereof. When the 18th Constitutional Amendment, roadmap for the devolution of central authority to the provinces, was being discussed and debated in the parliament in the early months of 2010, a small group of people floated a proposal. ‘Pakistan' had become far too loaded a name, they argued, conveying a sense of ill-fitting morality and religiosity and since the North-West Frontier Province was being renamed anyway, casting off its colonial baggage to become Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, it was perhaps time for a complete makeover. Rename the country the ‘Indus Republic', they urged, a name that took into account the country's complete history and (almost complete) geography. The river ties Pakistan together, they maintained, in manner unmatched by history, language, ethnicity or religion.

The river does seem to bring cultures together, even in the existing divisive times, in a manner much less visible elsewhere in the country.

By the waters of the Kabul river in Nowshera town in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, a squatter settlement is home to Punjabis and Sindhis; they left their respective homes after the 2010 floods and moved north along the river because they had heard that economic prospects were better there. Shrines and temples dot the banks of the river, paying homage to Hindu gods and Muslim Sufi saints; sometimes, as in the case of Jhoolay Lal, the patron saint of travellers and revered by believers of both Islam and Hinduism, it is difficult to spot the difference between the two. But this very fluidity of the culture around the river poses a fundamental problem: Who does the water belong to and who will decide how it is used? Does it have to have an ethnicity, nationality, or a religion for that matter, in order for a certain group of people to claim its ownership?

Among the 108,101 people slated for displacement by the construction of the Kalabagh Dam are the residents of Rukfaan, a small settlement on the bank of the Indus roughly a kilometer upstream of the ethereal red-blue line that marks the Indus-Kabul confluence. According to local lore, the sound of the river was once so loud here that Pir Pahai, a Kashmiri saint, threw a pebble into the water in frustration, complaining to God that either he would pray or the river could sing. God chose the pir — the river has been relatively quiet ever since, say locals.

The people of Rukfaan have been hearing about the dam for so long, they no longer know what to make of it. One villager points out the little stone markers on the cliffs on the opposite bank; put up by surveyors decades ago, they delineate the boundaries of the would-be Kalabagh Dam's water reservoir. At the moment, however, in place of this reservoir, there is life: Women stoop by the water to do their washing and little boys skip into the river, empty Dalda cans strapped to their stomachs to help them stay afloat. Boats whir up and down and across the river and overturned charpoys dot the banks — it is summertime and no man or boy bothers sleeping inside.

"We'd sacrifice it all for the nation," declares one elderly man. "It's our ancestors' land," say one woman. "They're buried here." "The land I have isn't very good," muses a young landholder. "The land I'll receive in compensation will be more fertile." "The fact that the dam hasn't been built as yet only means one thing," says another resident. "It means that Pir Pahai is safeguarding us." Untill 1970, it was the central government that decided where the water would go, to whom and how and when; West Pakistan functioned as ‘one unit' and, consequently, resources could be shifted with relative ease and impunity from one part of the ‘one unit' to the other. The formation of a federation put a spoke in the wheels of this manner of resource allocation; Sindh, for instance, refused to grant the land that had been promised to the people displaced by Tarbela Dam and, in fact, certain communities downstream demanded that they be compensated as well, arguing that the construction upstream had affected water flows to them, threatening and negatively impacting their lives and livelihood. Moreover, the smaller provinces questioned, all the water that was going to be stored in the mega-dams — exactly who would make use of it?

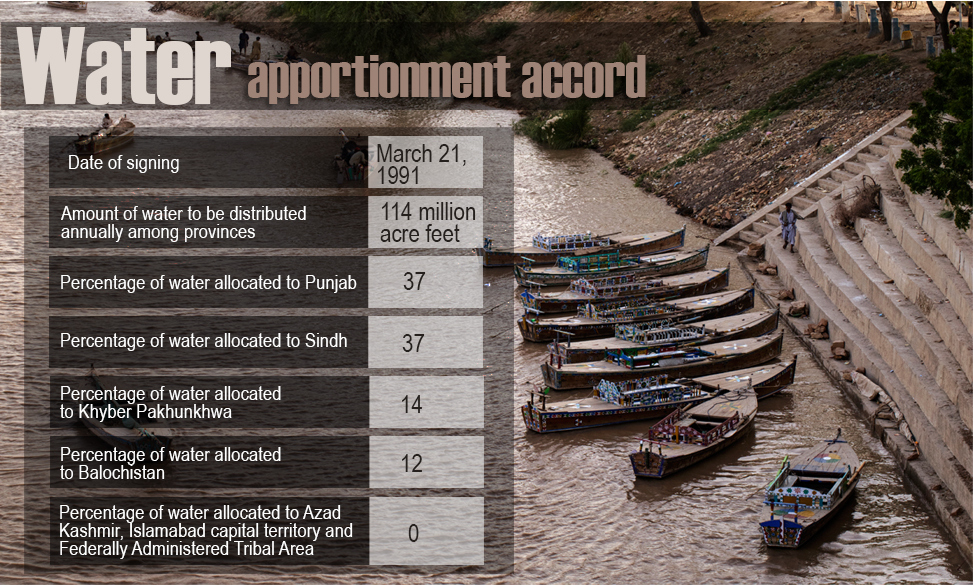

Because of this strife, explains Rao Irshad Ali Khan, who represents Punjab in the Indus River System Authority (Irsa), a federal institution mandated to divide water among the provinces, no major water engineering projects were initiated between the 1970s and the early 1990s. It was in 1991, after some nine attempts over the course of more than a century, that a water apportionment accord was finally formulated between the upper and the lower riparian regions of the Indus within Pakistan.

"It was a historic achievement," says Khan, an engineer with over thirty five years of experience with the Punjab irrigation department. Behind him on the wall of his office in Islamabad is the Irsa logo, a monochrome map of Pakistan with the Quranic edict: "Be just; it is next to piety." But even within the 1991 provincial water-sharing agreement, the ghost of Kalabagh Dam looms large. The original accord allocated water to the provinces based on a total of 114 million acre feet, a figure that assumed that additional storage structures would be created in due time — such as Kalabagh Dam. Punjab argues that the accord can only be implemented when 114 million acre feet of water becomes available to be distributed; in the event of a shortfall, which at the moment is almost every year, the provinces should revert to "historic patterns of usage", an arrangement under which Punjab actually gets more water than it would otherwise. Sindh, on the other hand, maintains that shortages should be shared equally between the provinces — but at an Irsa meeting in 2003, Punjab proposed that the smaller provinces, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, be exempt from the shortfall. Irsa functions like a Senate — each province nominates one member, as does the federation — and the tyranny of this structure allowed the Punjab proposal to be passed three votes to two.

"Sindh breathes when the Indus gushes," wrote Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, a revered 18th century Sindhi sufi poet. As a result of unfair apportionment, claim many Sindhis, the province is languishing. But here is the thing: Even if Sindh was to get its due share, it is quite likely that the farmers of Badin, one of the southernmost districts in the province, would still be out on the streets each year, protesting the lack of water, just as they were this August. In her essay carried in the Running on Empty report, Simi Kamal argued that the current water discourse requires redefinition: The real trouble isn't between provinces but between head, middle and tail farmlands in irrigated areas and different methods of managing water in areas that are arid or only fed by rain.

N

owhere perhaps are the lines (and swords) as clearly drawn as around one as-yet-unconstructed dam and nothing, it seems, is a better litmus test for one's ideas on nationhood and progress than the question of whether or not it should be built. In the public imagination, the proposed Kalabagh Dam has become many things: An answer, an excuse, a conspiracy against the federation.

Baba Kaala was a teenager that year, fifteen or perhaps sixteen years old. He lived then where he lives now, on the bank of the river Ravi, in a settlement called Sagian on the outskirts of Lahore. In order to cross the Ravi, he would take the boat or, if the current wasn't too strong, swim to the other side. But on the day the river ran dry, there was so little water he could place bricks on the river bed, hitch up his shalwar and simply walk across to the other bank.

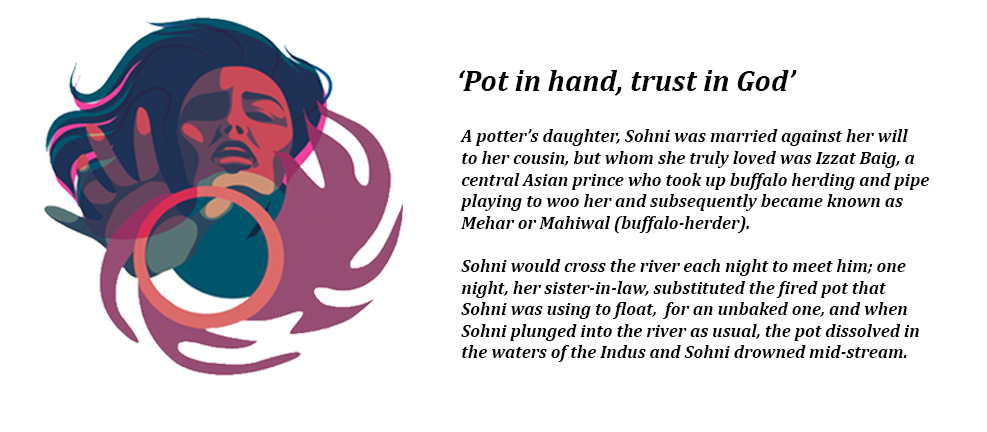

(Elsewhere, the humourous poet Anwar Masood quipped, the folk heroine Sohni prepared to make her nightly trip across the river Chenab to meet her lover, pitcher in hand — only to discover that India had halted the river.) India released the waters a month later but made it very clear that she would control the tributaries that she could: Ravi, Sutlej and the fading Beas. Pakistan scrambled to find a solution, appealing, in June 1949, to the International Court of Justice — but India refused to participate. Meanwhile, David Lilienthal, an American technocrat who had been touring the Indus basin, proposed a plan to alleviate Pakistan's "fears of deprivation and return to desert". As it turned out, this wasn't Lilienthal's primary concern; having recently become a partner in an international financial advisory and asset management firm, his "main interest at present", according to a confidential British memo, was that his scheme should involve "a lot of money". He suggested building dams all along the river.

The newly found World Bank was paying close attention. In August 1951, its president Eugene R Black wrote to the prime ministers of India and Pakistan, enclosing a copy of Lilienthal's proposal and offering his organisation's ‘good offices' for the execution of the scheme — and thus was born the Indus Waters Treaty. For a fixed sum of 62 million pounds sterling paid to Pakistan, India assumed control of Ravi, Beas and Sutlej and, with the assistance of the Bank, Pakistan embarked on a series of ambitious replacement works: two large dams, five barrages, one gated siphon and eight inter-river link canals.

Baba Kaala, a wrinkled old man now, refers to the treaty as "that time when [President] Ayub [Khan] sold the rivers" but there is an understanding among experts that the settlement was among the best options at hand at the time — a report by the Pakistan Institute for Legislative Development and Transparency goes so far as to call it the "most successful confidence building measure" between India and Pakistan.

But for hypernationalists, Indian control over water remains a source of paranoia and easy propaganda: Soon after the 2008 Mumbai terror attacks, Pakistani military officials began highlighting India's alleged violations of the Indus Water Treaty, suggesting that water issues constituted a "latent cause" of the ongoing conflict in Kashmir; a few months later the then President Asif Ali Zardari voiced similar concerns in a Washington Post op-ed. "The water crisis in Pakistan is directly linked to relations with India," he wrote, adding that failure to resolve the water imbroglio "could fuel the fires of discontent that lead to extremism and terrorism." In April 2010, Jamaatud Dawa chief Hafiz Saeed put it even more directly: India was "‘imposing war" on Pakistan through its water-related policies, he thundered at a rally in Lahore; his angry audience shouted slogans, warning that "either water would flow or blood".

The Balloki headworks on the Ravi river downstream from Lahore looks like any other irrigation structure in Pakistan: a mass of faded concrete trimmed with bright blue paint. Water flows lazily into canals, whatever little there is — according to an estimate offered by Irsa's Rao Irshad Ali Khan, Pakistan receives a combined average of 6 million acre feet of water from the three eastern tributaries to the Indus; by contrast, the three western rivers account for 139 million acre feet.

The rest of Ravi's water is rain and toxic waste; only three out of 100 industries using hazardous chemicals in Lahore treat their wastewater adequately, revealed a 2006 study by the World Bank, and almost all of them, directly or indirectly, drain their effluents in the river. Much like the Cuyahoga in Ohio, infamous as "the river that caught fire", the Ravi is so polluted that it sometimes appears to "ooze rather than flow".

Balloki is currently undergoing rehabilitation, according to a plaque at the site, a project for which the ADB has provided a loan of four billion rupees. According to an official at the barrage, this rehabilitation is necessary in case river flows increase. "But there's p-0ly any water in the Ravi," I say to the official, gesturing towards the sluggish river. "Yes, but there could be. India could release water."

Baba Kaala relates the story of when India last let water flow into the Ravi. The water rose above their roofs; Sagian was washed away. He remembers rounding up buffaloes that belonged to people living up the river; he then placed an ad in the local newspaper inviting claimants for the lost livestock. He still has that cutting saved.

That was roughly twenty five years ago, in 1988. "They did it after [General] Zia died," Baba Kaala says. "They didn't dare do it while Zia was alive."

I mention this date to the official at the Balloki Barrage. He sighs. "Yes, but that doesn't mean they won't do it again, does it?" At a recent press conference, Khwaja Asif floated the idea of revisions in the existing Indus Waters Treaty, claiming that it currently tilts heavily in India's favour. Such a view is likely to gain political traction in Pakistan in the light of some recent developments: The International Court of Arbitration recently announced its final ruling on the Kishanganga hydroelectric project, a run-of-the-river dam being built by India on a tributary of the Jhelum river in Indian-administered Kashmir and to which the Hague-based court has given a green light, stipulating only that a minimum flow of water is ensured at all times (the set minimum is far lower than the amount requested by Pakistan).

But as observers point out, Pakistan and India aren't the only claimants on the Indus and its various tributaries; China and Afghanistan have access to the water too and as the lower riparian in all these cases, it is in Pakistan's best interests to reach water-sharing agreements with these countries. The Kabul river alone brings 17 million acre feet of water from Afghanistan into Pakistan, part of which is stored in Warsak Dam and then used to irrigate the Peshawar Valley. Afghanistan has planned a series of hydro-electricity generation projects on the river (in which the country will be assisted, to the horror of our hypernationalists, by none other than India). This could affect water supply to the farmland growing wheat, sugarcane and tobacco, all economically strategic crops in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa which relies in large part to the output of fields to sustain its burgeoning population. And there is little awareness in the public sphere that there is already a dam constructed by another country on the Indus: The Shiquanhe, a run-of-the-river structure, built so discreetly by the Chinese in Tibet in the early 2000s that it completely threw off travel writer Alice Albinia, author of Empires of the Indus:

"Now that I am here [in western Tibet], I stand on the river's bank in confusion, wondering whether I am in the wrong place. There is a blue boot and a bicycle tyre where the water should be; Chinese instant-noodles are scattered about like flowers—but where is the water? My map clearly shows the Indus running straight through the middle of this town … I look through the list of Emergency Chinese in my guidebook and stop a passer-by: ‘Shooee?' I say. Water? Tsango? River? Darya?"

Despite this, Pakistan's fears of deprivation and return to desert remain tied to India and April 1, 1948 continues to be regarded as the starting point of the country's water troubles. But an emerging collection of voices is pointing towards another year, from an earlier time, which could be more instructive in identifying the source of our water woes — when a group of merchants from the tiny British Isles landed in the subcontinent and, over the course of time, conquered our rivers and changed the way we thought about them.

"T

he Indus is a foul and perplexing river," grumbled Lieutenant John Wood, an officer of the East India Company. The year was 1836: Wood, along with three other Company employees, had been despatched to Sindh to test the navigability of the river. Sailing into the mouth of the Indus on "the first steamboat that ever floated on its celebrated waters", the officers proudly unfurled the Union Jack but couldn't entirely shake off a sense of wariness. This was a river that didn't quite make sense to them.

The British colonisation of the river, like most colonial endeavours, was profit-oriented and the Indus was viewed in purely fiscal, and frankly adversarial, terms. "The shallow, shifting, treacherous nature of the river Indus," lamented the chairman of the Indus Steam Flotilla, W P Andrew, during the latter half of the nineteenth century, "makes it inefficient, uncertain, unsafe, costly." Indeed, as far as the British were concerned, the river's potential as a means of transport was proving to be rather disappointing – there were far too many shipwrecks, freight damage and passenger deaths. The conquest of Sindh, given the rising costs of its administration, was beginning to appear less and less "a useful piece of rascality".

"In the end," wrote Albinia, author of Empires of the Indus, "it was irrigation that rescued Britain's conquest of the Indus from financial disaster."

Engineering projects, primarily the introduction of perennial canals which flow throughout the year, had been initiated upstream on the Indus river system as early as the mid-nineteenth century (after the Company conquered Punjab in 1849) and, when famine struck northern India in 1878, the projects were further expedited. "By 1901, four of the five rivers of the Punjab had been ‘canalized' or dammed," wrote Albinia. "Grain poured out of the Punjab, feeding hungry mouths in India, and transmitting new taxes to London. The Punjab became a ‘model province' in British India: productive and peaceful." Consequently, the colonisers turned their eyes to Sindh.

The Governor of Bombay laid the foundation stone for Lloyd (later Sukkur) Barrage in 1923, at the time the world's largest irrigation project. Colonial interests, economic and political, were clearly vested in this barrage: The steady supply of raw material to Lancashire's cotton mills, for one; appeasement following the arrest of the top leaders of the Khilafat Movement, for another, many of whom had the support and cooperation of Sindh's pirs and, by extension, of the rural population.

The public narrative was quite literally a different story. The Barrage would "convert a desert into a garden," declared the project's Executive Engineer at the stone-laying ceremony. Moreover, it could potentially transform what nearly a century earlier British explorer Sir Ricp-0 Burton had referred to as the "general torpidity of Scindianism" and what had been expounded upon by the author of the 1907 Sindh Gazetteer in the following manner:

"The truth is that, in the absence of competition, ambition and every other stimulus which urges the husbandsman to get the most he can out of his field, the Sindhi has for generations cherished the ideal of allowing his field to divorce him as little as is possible from his hookah as might be compatible with keeping the latter filled."

In a nutshell, then, science was saving Sindh (and the Sindhi). Modernity was knocking at the door. The idea caught hold of the local imagination: Symbols of technology (aeroplanes, cars) began appearing in local tales and riddles and poets started composing verses commemorating the barrage. Wrote Khano Panhwar, a young Sindhi poet, in the early 1930s:

Implicit in all this was the idea that such progress was a ‘gift' from the British, masters in the material and technological fields, to the locals, who were more occupied with ‘culture' and ‘spirit' and indeed, the hookah. A few days after the inauguration of the Barrage, the following article appeared in the Times of India:

"On the morning after the official opening of the Barrage by His Excellency the Viceroy, there might have been witnessed a second opening ceremony, in its way no less impressive. A white-bearded and saffron-robed saint from the north stretched his arms in benediction over each of the canals and in a loud voice intoned a solemn song of praise and prophecy. He gave rather more thanks to God and less to the Engineers than His Excellency had done and was less concerned with history and more with poetry. He looked like a man from a thirsty land, and his picture of the blessings brought by irrigation was a vivid one."

The ode to the god of irrigation, who lifts people out of their torpor through the benign agency of dammed rivers, could not have been more inspired.

Daniel Haines, a British academic who analysed the opening ceremonies of the three barrages constructed on the Indus in Sindh — one during the imperial period (Lloyd/Sukkur) and two following the creation of Pakistan (Kotri and Guddu) — noted that despite the changed political contexts, the ceremonies were curiously similar, particularly in their notion of what constituted progress: "The terms ‘development', ‘modernity' and ‘progress' in the Imperial and Pakistani lexicons were politically and morally loaded and, crucially, were considered to be the domains of the state and its agents." When Pakistan came into being, the state merely continued the colonial discourse of the triumph of scientific irrigation over the native cultivator's techniques and, either consciously or unconsciously, took on the colonisers' self-promoting role. This wasn't specific to Pakistan; around the same time, Jawaharlal Nehru anointed dams as the "temples of modern India".

By 1957, this mindset was firmly in place. At the foundation stone-laying ceremony for the Guddu Barrage, in an address presented to President Iskander Mirza by the West Pakistan Minister of Communications and Works, engineering expertise was presented as fundamental to national development:

"In the development of any country, the Engineers have to play a great part. In our young country, we need more Engineers and good Engineers. The task of constructing this new Nation will fall mainly on their shoulders."

"T

hey don't make them like they used to," says Ishaq Mughriye, an activist based in Kambar Shahdadkot and head of the area's abaadkaar board. He is referring to the flood managers and irrigation officials stationed in the area — there was a time, he says, when an official could look at a distributary and correctly estimate the amount of water flowing through it. Now, he laments, they don't even bother leaving their airconditioned offices for a field visit.

The 2010-2011 floods raised serious questions about the country's irrigation structure and the extent to which it contributed to the scale and extent of the disaster. The findings of the Punjab Flood Commission, constituted to investigate the 2010 floods in the province, acknowledged the serious lapses committed by concerned officials, who "saw the glorious Indus pass by knowing little what to do." Much of the damage was due to these "inexperienced, incompetent, ignorant and nervous flood managers, pirouetting and gyrating in meaningless frenzy — without any preparedness, plan, equipment or strategy." Indeed, continued the indignant report, "the inability of the flood managers" was reminiscent of a childhood nursery rhyme. It then went on to quote the final three lines from Humpty Dumpty.

Engineer Zulfiqar Ali, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Engineering and Technology (UET) in Lahore, claims that we haven't learned our lesson, that mismanagement is still continuing apace. Like Mushtaq Gaadi, he believes that the flawed rehabilitation of Taunsa Barrage in 2007, for which he says 11 billion rupees were borrowed from the World Bank, contributed to the devastation of Muzaffargarh in 2010. The Punjab Flood Commission has not addressed these allegations, but Dr Ali claims this is because the project designer and the member of the advisory group were part of the inquiry tribunal.

Now, he claims, something similar is happening at Jinnah Barrage further upstream. In an article highlighting the issue, he wrote: "Common sense dictates that a hurdle in the flow of water will raise the water level on the upstream. Then why is a 6 ft high wall (sub-weir) at 800 ft d/s [downstream] of Jinnah Barrage being constructed? Who are the originators, checkers and approvers of this conceptually wrong project?"

"If money is being spent on unnecessary rehabilitation, that's one thing," he says, sitting in the living room within the UET premises. But if the rehabilitation is ill-planned, he argues, or if it is a source of potential danger, that's another story altogether. He says that he has written to the former Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, to former President Asif Ali Zardari; he even filed a petition in court, a petition that was heard but then dismissed. But he says he will continue trying.

"Someone needs to raise their voice."

O

n a warm July evening, a group of villagers sat solemnly by the Indus. The sun was about to set, its crepescular rays rippling on the water; a man was speaking, listing the injustices of contract-based fishing system in Punjab. The little assembly, comprising men and women as well as a few scattered children, had the feel of being the village equivalent of a town-hall meeting. The locals called it a sath.

The lok saths or peoples' tribunals first began in August 2003 over the implications of the construction of the 274-kilometer long Chashma Right Bank Canal. It appeared that the architects of the canal, which runs parallel to the Indus, had forgotten about the hill torrents that carried water, considerable amounts of it, down from the Sulaiman Range mountains into the river. Instead of draining into the Indus, the water now crashes against the canal, causing extensive flooding and subsequent destruction of homes, crops and lives — every year.

"There is this idea that canal irrigation brings order," says Asad Farooq, a professor of law at the Lahore University of Management Sciences who works with indigenous communities on water-related issues. "And accompanying this is the assumption that what existed previously was chaos. It's an interesting dichotomy: Order/chaos. But when you actually go and talk to the people, you realise it's the exact opposite." It's the new system, he says, with its attendant state machinery, that locals find chaotic; it disrupts what they are familiar with.

In the case of the Chashma Right Bank Canal, says Farooq, the engineers completely disregarded the traditional irrigation system in the area, known as rowd kohee¬, literally mountain water. The communities settled on the right bank of the river would band together and build small, temporary dams to slow and store the water rushing down from the hills, then disperse it through a system of sharing.

With the construction of the canal and its attendant problems, the affected communities filed inspection claims with the Asian Development Bank, which had funded most of the 245-million dollar canal project; the claim was inspected but the process was deferred. The disillusioned communities came to a conclusion: there was no need to engage with the state. It was time to "take back destiny".

The peoples' tribunals aren't about overt political struggle — they are, in fact, a process of bearing witness. For the villagers participating in the tribunals, it was a way of recording their version of what was happening and of how they thought they should react to what was happening to them. Over the course of time, saths have evolved into a unique form of non-violent resistance: villagers refuse to pay irrigation taxes, commit to breach the canal when it threatens lives, and have, on occasion, pledged indefinite hunger strikes outside the ADB office in Islamabad.

"So what do you think of my village?" asks Fazle Rab, a local activist and one of the leading members of the sath, later that evening. Smiling wryly, he gestures at two parallel canals crashing through the fields across from his verandah. He has to raise his voice to make himself heard; the whirring of multiple small Chinese water pumps, locally known as Peters, not quite in sync, was tearing the night air.

I smile back sadly and tell him it is beautiful still.

"All of this used to be so prosperous," continues Ashu, gesturing at the expanse around him. "We used to call it kacchi, phoolon di pacchi (basket of flowers)."

Karor Lal Esan is located on the eastern bank of the Indus in district Layyah; across the river looms the mysterious Sulaiman range. According to local lore, Hazrat Lal Esan, grandfather of the great Bahauddin Zakariya, stood on the bank of the river here and recited Surah Yaseen ten million times. The incident gave the town, known before as Depalpur, its name.

ear midnight on a moonless night, a white-haired man makes his way towards the river, tailed by an unusual entourage: a horse, a tractor, a young boy and several men with their shalwars rolled up to their knees and their sleeves to their elbows. They pause before a small rivulet, a minor channel of the river, before crossing it —the men wading, the horse sloshing, the tractor trundling through. When they reach the river bank, they unpack supplies from the tractor, lay out a picnic blanket, settle down and fall silent. Then Ashu Lal begins to speak. "You couldn't reach this point before," he says. "It would take an entire day. You would need a boat." Ashu Lal is a doctor by profession but in this town of Karor Lal Esan -- in fact, in all of the Seraiki wasabi, and perhaps a little beyond -- it is his poetry that he is known for. Much of his literary output is a paean to the river and, just as often, a requiem. The young boy, the only person in the group who shuns the reverential circle around Ashu and instead attempts to strike up a conversation with the horse, is Ashu's son Hans, named after a white-winged bird native to the Indus. The name choice is part tribute, part aspiration: The hamsa, given its ability to walk on the earth, fly in the sky and swim in the water, transcends the limitations of the creatures around it.

Ashu Lal does not carry a cell phone. He thinks that the money that once upon a time would have been used to, say, raise a clutch of chickens is now subsumed by phone credit. He worries, often and at length, about the impact that television is having on his son and about precisely what it is that he is being taught at school. He is apprehensive, also, about the bridge being built across the river — it will bring crime to their doorstep, he fears. After all, it is well known that the Sulaiman mountains are a favourite hiding spot for outlaws. The development he sees around him, in his mind, spells doom.

"When we wanted a road, they were too busy building one from Taunsa to Lahore," he says, as an indictment of the development priorities of the bureaucrats and politicians based in the faraway capital of Punjab.

Ashu Lal's memories of growing up by the river have a prelapsarian feel to them, populated as they are by cranes and dolphins and barasinghas; the first memory he has of ever feeling shocked is when, as a child, he watched two huntsmen bound after a stag, then shoot it point-blank. His suspicion of technology borders on neo-Luddism but it appears to be based on a more widely held apprehension that ‘development' is a selective benefactress, that it facilitates the flow of resources from one region to another, persistently making one poorer and the other richer. Ashu Lal fears that his region is among those that have lost out.

A small sound punctures the air, a rustle in the river.

"Did you hear that?" asks Ashu. "It's the first time that we've heard anything."

He looks wistfully towards the water. "There was a time when the river wouldn't let you talk. Now it is lying silent and we're the ones left talking."

F

ew forces have so clearly shaped the destiny of human civilisations as water or, indeed, have as firmly captured the human imagination. Consequently, the ability to shape water, to make it climb heights and cascade down, to funnel it through airless passages straight to agricultural fields and urban homes, is regarded as one of man's greatest achievements. For the poet, there may be considerable transcendental value in watching a river run wild and free. For the engineer, there is equal thrill in watching water leap, with leonine ferocity, from the spillways of a dam.

The Indus roars at Tarbela. The dam is a monument to ordered progress, so much so that even a scraggly goat munching grass by the spillways looks out of place. It is also, admittedly, a testament to a young country's will and ambition. "Tarbela makes one think of hubris: the hero's challenge to the gods that was the theme of the tragedies of ancient Greece," an American engineer had warned at the time. There were tragedies: Shortly after the dam became operational, a tunnel collapsed and, pierced with guilt at the ensuing damage, one of the engineers committed suicide. But on the whole, the project was, and continues to be, touted as a success: It doubled water supply during the dry months, recovered its costs in due time and provided the country, or at least certain parts of it, with cheap electricity.

The dream, an official at Tarbela tells me, is for all three dams – Diamer-Bhasha, Tarbela and Kalabagh – to be functional on the Indus. Water would flow through Bhasha in Gilgit-Baltistan, generating electricity, then flow through Tarbela in Haripur, generating some more electricity, and finally flow to Kalabagh in Mianwali, where it could be stored or released, depending on irrigation needs. In case of floods along the lines experienced in 2010 and 2011, the water could be stored in all three dams. What could be a better solution to the country's water and energy needs?

But just outside the premises of the dam, in the town of Ghazi, an old man m-4ing a wheelbarrow down the street complains of the amount of load shedding in the area. "Who is getting this electricity?" he asks, jabbing a thumb in the direction of the dam. "We aren't."

At Khalabat township, one of the settlements for the affectees of Tarbela dam, the Khan of Khabbal, whose village is among those that now lies beneath the Tarbela reservoir, says something similar. "I don't want these lights, I don't want this electricity," he had proclaimed, pointing at the churning fan above him. "I have seen a piece of heaven and I want it back."

Back in the Wapda office at Tarbela, a senior official, surrounded by charts and numbers and figures and hydraulic models, waxes eloquent about the many gifts of the dam. It is not easy to pay a visit to the dam site — with control comes the need to preserve it and the structure is a high-risk strategic target. In 2007, a deadly attack took place on an army base within the premises; the Taliban were suspected to be the likely perpetrators.

But the official is a positive man, his cheery optimism characteristic of the can-do attitude of engineers. Gesturing expansively, he describes the many amenities available inside the gate community of officials deployed at the dam. There is uninterrupted electricity. There are schools for the children of the officials—one for boys and one for girls. There is a college. There is even a hockey field. He lists these off as if they are personal achievements.

"We have everything here," he says, beaming.

"Really, when you think about it, this is like heaven on earth."