AFTER every general election the press publishes statistics of persons facing grave criminal charges who were elected to parliament and to the state assemblies. In one state, nearly half of the 100 plus MLAs have criminal cases against them.

It will help a lot if one crucial question is answered clearly and candidly — why do the people vote for such people of ill-repute and vote them into legislatures, in very many cases, with massive majorities?

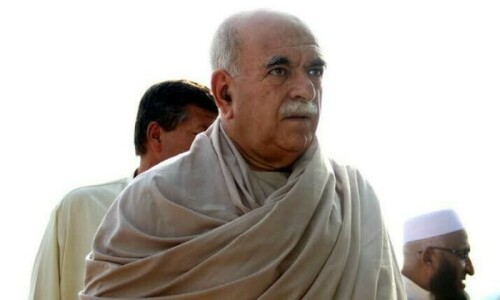

The malaise is deepest in the northern belt of India, especially in three states — Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. A case which earned notoriety last February concerned one Raghuraj Pratap Singh aka Raja Bhaiya who assiduously cultivated the image of a Robin Hood in his district which became his fiefdom. His case helps us to understand the problem better.

According to an informed correspondent based in UP’s capital Lucknow, this 43-year old minor princeling faces eight criminal cases for abduction, murder, attempt to murder, violence and land grabbing. Yet several criminal cases against him were withdrawn.

He has won five times in a row from his Assembly seat since 1993 when he was the youngest MLA at 26. “His elections have always been one-sided ensuring him victories by huge margins; in 1996, 2002 and 2012, he won by margins of over 80,000 votes,” says the correspondent.

That the present Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav made him minister for jails, food and civil supplies last year reveals the depths of the politicians’ cynicism. He was obliged to resign on March 4 this year after the wife of Ziaul Haq, an upright deputy superintendent of police, named Raja as the prime culprit behind the murder of her husband.

Consider for a moment whether Silvio Berlusconi would stand any chance in the United Kingdom, France, Germany or Switzerland. Each may have an extremist party of the right reflecting the popular mood against, say, immigrants. But a Berlusconi would have no hope of becoming the country’s chief executive.

There must be something peculiar about Italy’s political culture and the state of its political parties which helps to explain the phenomenon. Those factors are not hard to identify — rampant corruption in society which breeds cynicism all round, a dysfunctional party system and a state too weak and too unready to redress long-standing popular grievances.

That brings us nearer the truth which India’s northern belt reflects vividly. It is, of course, not the only patch on earth where sordid politics are played out. One can think of many parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America which share the scourge. The case of Raghuraj Pratap Singh, mentioned in some detail, is typical of the region; lineage helped him a bit to carve out a fiefdom. It was his own successful attempt to carve out a Robin Hood image which accounts for the clout he came to wield.

It is precisely in this belt in northern India that you find a combination of the factors which drives people to plump for the unworthy. Those factors are many.

First a steep decline in the state’s power; its loss of monopoly on the use of force; inability to maintain law and order and protect the weak and underprivileged; secondly, debasement of the political process.

Political parties and politicians who run them turn their back on the people’s needs and grievances, and the social and economic wrongs under which they languish.

The judiciary is too slow and sluggish to provide relief; some of its elements are not exactly shining examples of probity themselves. Powerful landlords, industrialists and businessmen spread their bounty freely to patronise the willing in the judiciary, the civil service and, first and foremost, politicians, whether in power or in opposition.

In such a set-up, to whom can the hapless citizen turn but to the strong man who offers relief for the price of his vote. Entrenched within the entire system from the ministers down to the headman in the villages he acts as mediator between the citizen and the state apparatus. The politician needs him for his money and his strong men, during the elections.

All this became possible because the politician abdicated his true function in society and betrayed the public trust. Legislation is an escapist route. Equally escapist and far more destructive is the rejection of the political process. What Prof Bernard Crick wrote in his classic In Defence of Politics should serve as a caution against such sweeping a rejection: “Politics deserve much praise. Politics is a preoccupation of free men, and its existence is a test of freedom.” This explains why dictators abuse politics and politicians. Politics is not neat. It is messy, but all-pervasive in offices, private institutions, sports associations, student bodies, etc. Power raises the stakes; it does not alter the nature of politics.

Diverse and complicating interests shape society. It is the function of the politician to articulate them in an informed manner and work for a compromise which, however imperfectly, ensures peace and progress.

In doing so the politician does not perform a priestly, still less saintly, role. He is in politics very much in quest of power. The difference between him and the gangster is that the politician is committed also to the public weal.

He does promote himself, to be sure; but he never violates the rules of the game, the conventions of democratic governance, and, when it comes to the crunch, puts the public interest above his own.

This is after all, what characterised politics not too long ago. That was when politics was not another avenue for acquiring wealth.

None of this suggests, of course, that the law should not address the problem. It only suggests that legal remedies suffer from inherent limitations in tackling social and political problems. A multi-pronged approach is necessary. Legislation backed by relentless media exposure and independent NGOs alerting civil society to the politician-criminal nexus is needed.

The writer is an author and a lawyer.