Questionable voters’ lists

MONTHS before the event, the legitimacy of the next elections is already being questioned by the opposition parties. These early doubts concerning the legality of the electoral process may be unfortunate but are by no means surprising. Claims of pre-poll rigging have been flying thick and fast ever since the new voters’ lists were unveiled by the Election Commission, with the Pakistan People’s Party — which won the popular vote in 2002 — in the forefront of those crying foul. Also upset by what appear to be glaring inconsistencies in the draft electoral rolls is the Pakistan Muslim League faction headed by Mr Nawaz Sharif. The religio-political alliance operating under the umbrella of the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal has also expressed doubts about the veracity of the new lists — a concern also echoed by the All Pakistan Minorities Alliance which claims that 20 per cent of non-Muslim voters have been excluded. The fears voiced by opposition parties of all shades of opinion, as well as independent groups, are far from unfounded. According to the electoral rolls made public across the country on June 12, there are a little over 52 million registered voters in the country — down nearly 20 million from the number deemed eligible to vote in 2002.

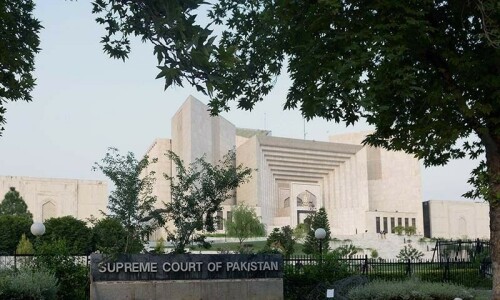

Some claim that the number of ‘missing’ voters is even higher, anywhere between 30 and 37 million, because of the projected increase in the over-18 population since 2002. For its part, the Election Commission defends the sharp decline on the grounds that people without computerised national identity cards (CNICs) have not been included in the electoral rolls. Invoking Article 51(2) of the Constitution, the PPP has challenged this criterion in the Supreme Court and has asked that all eligible voters be registered by the Election Commission irrespective of whether or not they possess CNICs. PPP chairperson Benazir Bhutto has claimed in her petition before the apex court that 4.7 million voters have been disenfranchised in 23 districts of Sindh considered to be People’s Party strongholds. The enumeration exercise in Sindh, the petition maintains, has been carried out dishonestly, by the MQM in the urban centres and by the chief minister’s PML-Q in the rural areas of the province. Another 15 million, Ms Bhutto alleges, have been dropped from Punjab’s electoral rolls. In Balochistan, meanwhile, the number of eligible male and female voters is said to have risen by 104 and 140 per cent respectively. The PML-N has also filed a petition in the Supreme Court, claiming that the draft electoral rolls are based on “dishonest assessment and enumeration”.

Pakistan today stands at a crossroads. Buffeted by crises of its own creation, the government is fast losing its grip on power and its credibility among the people. Seen against this backdrop of uncertainty, it is of critical importance that the next elections be free and fair. They will serve as the acid test of the government’s democratic credentials and can play a major role in shaping the future course of the country. A truly independent Election Commission is of the essence, as is the announcement of a schedule for the polls. The president has a choice: he can either put the country back on the road to genuine democracy or take shelter behind an engineered exercise conducted on the lines of the 2002 polls. The mistakes of the past must not be repeated.

Non-judicial actors

JUSTICE Khalilur Rahman Ramday’s remarks on Tuesday about non-judicial actors in Pakistan’s constitutional history contain a lot of truth. During the hearing of the petition challenging the presidential reference against the Chief Justice, he admitted that the judiciary had no doubt legitimised military takeovers, but pointed out that politicians, too, had accepted the military leaders and collaborated with them. While the Supreme Court gave Gen Pervez Musharraf three years in which to end military rule and hold general elections, the politicians, he said, authorised him to rule for five years by passing the 17th Amendment. This is not the only example. Earlier in our history, both Ayub and Zia found willing tools among the politicians when the two generals created the king’s party and named it Muslim League each time. Today also, some leading politicians, who once belonged to parties which are now in the opposition, are members of the ruling Muslim League. Similarly, the political parties’ attitude towards a general has depended on expediency. At present, some religious parties are in the forefront of the demand for President Pervez Musharraf to shed his uniform, but these very parties supported Ziaul Haq to the hilt when he remained army chief and president for full 11 years. Most regrettably, our politicians do not see beyond their nose tips and opt for short-term gains. This chicanery destroyed the democratic experience between 1988 and 1999, for every now and then politicians in the opposition appealed to the army to “do its duty” while trying to overthrow an elected government.

The dialogue between Justice Ramday and Barrister Aitzaz Ahsan was lively. But surprisingly Mr Ahsan’s list of institutions responsible for the country’s predicament omitted the bureaucracy. This is a surprising omission, for the bureaucracy collaborated with the generals to the full, took part in the persecution of the dictators’ political enemies, was instrumental in spawning a culture of corruption and patronage, and obeyed orders in violation of the law and Constitution. Pakistanis may blame each other for the country’s failure to develop a democratic system, but history will hold the entire nation responsible for the country’s misfortunes. Let us accept it — it is a collective failure.

Fighting drug abuse

IT IS paradoxical that while Pakistan has successfully eliminated poppy cultivation, the number of drug addicts in the country has been on the rise. With more than half a million drug users, Pakistan has among the highest addiction rates in the world. The toll that addiction takes can only be imagined, for not only does substance abuse cause physical harm to drug users; it is also a financial drain on their families. Although drug addicts are usually unemployed, their addiction is such that they have no qualms about spending the hard-earned income of other family members on drugs. It is a habit few can break free of, unless it is treated as a medical one that can be corrected through counselling and intensive rehabilitation programmes. Unfortunately, there are just a handful of such programmes across the country.

It is easy to blame the high addiction rate in Pakistan on trafficking that originates from Afghanistan where poppy cultivation is rampant and where the might of the drug barons is such that it cannot be countered by the Kabul government. But the question must be asked: what are we doing at our end to stop addiction? Drug users — and these are to be found in every segment of society — must be seen as victims of societal frustrations and iniquities when it comes to wealth distribution. Obviously, these cannot be wished away but the government must show more sensitivity to the issue by examining ways and means to discourage the resort to drugs. The public, too, needs to be sensitised so that addiction is treated as a harmful habit. It is only from a common platform that addicts, their families, the government and the public at large can take action to contain the number of drug addicts.

Choosing the right option

AMERICA has its Declaration of Independence, we have the Pakistan Resolution. India has its ‘tryst with destiny’, we have the ‘doctrine of necessity’. England has the Magna Carta, we have the Government of India Act, 1935.

Issued in 1215, the Magna Carta is considered to be the most important legal document in the history of democracy and has influenced most world constitutions, including that of the US. The guiding factor for all our constitutions has been the Government of India Act, 1935.

Enter Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif with their Charter of Democracy. They are to be commended for the Charter’s edifying contents even if the fanfare of its launch was drowned by the din of the Lal Masjid brigade’s clamour for the enforcement of sharia.

Despite the party activists trumpeting the Charter as their leaders’ legacy to Pakistan much as, perhaps, the Magna Carta was for England, it is unlikely that Benazir or Nawaz had the Magna Carta even dimly in mind when drawing up their Charter. There is little doubt that Benazir believes the 1970’s mantra of roti, kapra, makan, even if it has remained just that – a mantra, nearer to people’s aspirations than the Magna Carta ever was. Nawaz probably couldn’t care less if the Magna Carta is what it is claimed to be or a special ‘manjha’ used in Lahore’s Basant festival.

Whether their Charter will become the guiding light for their future constitutional conduct is yet to be tested. This will be seen if Benazir and Nawaz Sharif are allowed to take part in the next elections and, as in 1988, one is able to gain, or cobble together, more seats in parliament than the other. If the Charter has any meaning for its ‘masterminds’, then the loser, as per custom, will take the seat of the leader of the opposition and faithfully function in that capacity and not, as in 1988, abandon the role to become a powerful provincial chief minister.

This time the Charter of Democracy should result in something that happened in France in the recent elections: the rightist winner became the president and the leftist loser accepted the defeat gracefully, vowing to pursue her leftist agenda in the opposition but, at the same time, working with the rightist president to ensure France remains a leading country in this century.

The 1988 elections were a defining moment for Pakistan. After eleven long years of tyrannical despotism which, perhaps, mark the most degenerate period in the country’s history and in the aftermath of which Pakistan continues to smoulder, Benazir and Nawaz Sharif, when they had the opportunity, failed to avail themselves of it to lead the country out of reach for those who have ruled and exploited it since it’s birth, either through force of the hereditary power of land ownership, or through the barrel of the gun.

Nawaz Sharif directly, and Benazir, perhaps at one remove, are both products of martial laws. There was more marauding of the land than its cultivation as a democratic model during the two tenures of each as prime minister. The hope that they would plant, grow and nurture democracy remained just that – a hope. Both proved to be poor farmers of democracy. After over ten years behind the plough of democracy between them, all the two reaped were one way tickets – one to Britain and the other to Saudi Arabia.

Their Charter of Democracy notwithstanding, neither Benazir nor Nawaz, have shown in any concrete way that they would do anything different if given a third chance.

The two tenures of each adding to little over a decade are commonly regarded as the ‘lost decade’, but both appear to be undaunted. Neither has admitted to making mistakes or shown any hint of remorse that when given more than one opportunity each, to lead the country towards a democratic future, they wasted it.

Enter Gen. Musharraf, the Chief Justice and the black coats. The nation owes a debt of gratitude to all three for setting into motion a process that could lead to freeing the judiciary from sixty years of subservience to the executive.

Gen. Musharraf helped, however unwittingly, by not acting to contain the tumult the cause set off, instead of bolstering the tumult through thoughtless actions. The Chief Justice is owed appreciation for not succumbing to intimidation and for standing firm. The black coats deserve recognition for igniting the fuse that turned the discontent with the state of justice in the land into a protest of hitherto unknown proportions. All three are to be acclaimed for awakening a sleeping judiciary and, hopefully, filling it with a deep resolve for independence.

The opposition parties merit appreciation for being there even if their purpose was party projection to gain political mileage. They did somewhat more than just stand and stare, although they also serve who do just that. However, the opposition political parties would serve the cause of an independent judiciary better by not trying to turn the lawyers movement into one of their own. They have to maintain a respectful distance as supporters, not as participants, of a movement in the launch of which they had no role.

If the tumult for judicial independence over the past few months results in the writ of the judiciary being decisively established as an independent institution, that would be a major achievement. The option of recourse to courts that not only dispense justice, but are seen by the people to do so, is one of the major factors which give power to a people. Denial of justice is one of most powerful tools to keep a people suppressed.

Since its birth, Pakistan has had rulers whose paramount concern has been the maintenance of the status quo – keeping the people grovelling in poverty, wallowing in illiteracy, negation of their basis under the rulership of landowners – a suppressed, un-empowered people are a guarantee for the continuation of the landowners’ over in lordship and their privileged position as rulers. Denial of justice has been a critical tool used for this purpose.

The judiciary in Pakistan has had to contend with the fact that its work and actions have to be in line with the rulers’ interests. The courts do not have the freedom to become a natural recourse for unwarranted or legally blemished executive decisions.

Whenever a judicial action has clashed with the rulers’ interests there has been trouble, including a physical assault on the Supreme Court by activists of a political party headed by one of the authors of the Charter of Democracy. As the ruling class sees it, an independent judiciary which dispenses justice on merit will be the beginning of the undoing of its hold on the power structure of the country. It would amount to reining in the rulers and empowering the people, something which the country’s ruling class cannot, and will not, easily stomach.

The present times are rightly seen as defining moments for the country. There have been similar moments before too which, if they had not been let pass and the opportunity wanted, the country’s destiny would have been different today. President Musharraf probably has varied options – power sharing with some others, declaring an emergency, military intervention – to retrieve the situation for himself. Such options, however, will at best amount to a short-term respite, not a final way out. President Musharraf must find a way to resolve the problem on a lasting basis and in a way that, first of all, is good for the country, and good for its people. If he goes for such an option, he will come out the winner, whether if in the process he ends up retaining power or losing it.

The time has come and it is now, for President Musharraf to deliver on his ‘Pakistan First’ pledge. He should shed his ego and break free of those who proffer tailored advice – tailored to fit them, reinstate the CJ, admit he made a mistakes, take the blame for it, not pass the buck which a leader never does, announce he will shed the uniform to contest elections as a civilian under a caretaker government and an independent election commissioner and that, subject to no legal hitches which only the courts and the election commissioner can decide, Benazir and Nawaz Sharif should be free to contest the elections.

Additionally, the president should cause bills to be introduced in the present National Assembly which are designed to reinforce the constitutional provisions on the independence of the judiciary and the freedom of the media, to make it difficult for successor governments to violate these.

The bills on judicial and media freedom will be welcomed widely by all except, perhaps, by most political parties. However, no political party in effect wishes to see the twin ‘menace’ of judicial and media freedom to become a reality to plague them during their time in power. They will all be in a quandary on how to vote for the bills.

What these actions will minimally result in will be to throw the present lines drawn up against the president into total disarray. His past mistakes will be forgotten. The president, and his bold actions, will be on the centre stage from where he can continue to underscore his decision to honour his ‘Pakistan First’ pledge, regardless of the outcome of this for him personally. He will find the people responsive even if, in the beginning, hesitant to be so.

Above all, ‘Pakistan First’ actions by President Musharraf will mark a new political beginning for the country and, perhaps, for himself. It will be hard for future rulers, after the example of President Musharraf, to revert to their old practice. The people and civil society empowered with a free judiciary, and a free media, will not permit it.

The writer is a retired corporate executive. husainsk@cyber.net.pk

| © DAWN Group of Newspapers, 2007 |

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.