FOR sometime now, the indicators of growth and investment appear to have acquired permanence at a low level of equilibrium. Compared with growth rates of 5.5pc throughout the 1980s and the first six to seven years of the 21st century, the economy has been crawling at just over 3pc on average.

For us, the domestic market has been the basic determinant of the pace, pattern and level of economic growth because we focused on creating an economic structure that tended to protect industry, in the forlorn hope that the protected sectors would eventually become competitive and be able to hold their own in global markets.

This failure resulted in the growth of an export structure that was heavily dependent on one crop — cotton — in which we had a comparative advantage in the ‘static’ (rather than dynamic) sense, instead of nurturing and promoting an export culture that encouraged entrepreneurs with ideas, innovative capabilities and risk-taking urges.

But, for exports of a single-crop economy to become the driving force for raising the level of economic activity (as is being hoped for after the granting of GSP Plus status) always required an astronomical increase in exports. This was so notwithstanding the lack of skills required to increase the volume of value-added exports enabling us to not just narrow our trade deficits but also contribute to the settlement of our foreign debts in the foreseeable future.

However, our export performance has been modest in comparison with the increase in the trade deficit and debt-servicing obligations. Our capacity to meet our external payments from export earnings has not improved, if it has not diminished progressively. Therefore, on the one hand, through a series of policy distortions we fostered the growth of an industrial structure on the artificial crutches of exemptions and concessions. On the other hand, a clichéd claim that the country has no export surpluses became part of the common refrain. But no one explained whether Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia and China waited for export surpluses to emerge before they entered international markets. And, more importantly, this line of argument seemed to suggest that Sialkot had a surplus of five million footballs before entrepreneurs there started exporting footballs.

And while some reforms were introduced in the early 1990s to deregulate industrial licensing and investment procedures the errors of omission and commission of these reforms were that they were made before trade liberalisation. For instance, the sugar industry, motor vehicle assemblers, the engineering and fertiliser industry and the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association were pampered — the last two sub-sectors through the suppression of the administered price of gas, which continues to be subsidised for the captive power plants of the APTMA members.

In my view, this was a wrongly sequenced policy. The result was that a major portion of Pakistan’s industry either sought all sorts of concessions to compete internationally (with little effort to improve their productivity) or focused on the domestic market (supported, whenever necessary, by the state stepping in through protective measures or assistance under what came to be known as the ‘SRO culture’).

The economy, despite the smuggled goods and goods brought in by Pakistani migrants under the baggage allowance schemes, continued to be a closed one, as parts of the industrial sector that could not compete internationally survived, if not flourished, through the protection provided by less transparent specific policies and instruments (discriminatory taxation, high import duties and subsidies).

The ‘infant’ who was ‘protected’ from competition in anticipation that he would ‘grow’ up, remained lazy, never putting in the effort to become strong enough to compete globally without the help of these props. These arrangements represented a cosy pact between inefficient producers and the bureaucracy, whereby the former were provided opportunities of ‘extracting rents’ outside the budgetary proposals approved by parliament.

Consequently, the growth of one domestic industry created the market for another — thus all such markets grew together with hardly any signs that would indicate which ones would continue to grow or shrink over time. Such is the weakness of closed economies. Growth is neither influenced by nor predicated upon our international comparative advantage based on the ability to compete without a contrived support structure.

In many sub-sectors of industry capacities were created on the strength government expenditures run wild with successive governments spending as if tomorrow would never come. Now they have to be protected from competition for political reasons, particularly in periods of low growth with understandable worries about unemployment ensuing from closures.

Resultantly, all kinds of industries, operating with varying degrees of efficiency and inefficiency flourished, with their inability to compete internationally being glaring examples of the distortions that have been created by such policies.

The crisis of the industrial structure today, especially that plaguing the traditional sub-sectors, is an outcome of this piecemeal opening up of the trading sector. And the cost to the economy of this lack of a level playing field and the protection to some sub-sectors of private and public industries because of the wrong sequencing of reform has been huge with scarce resources being tied up in the inefficient production of goods.

This cost was compounded by the different rates of duties applied on components and sub-components, which incentivised corruption as well as the misdeclaration of imports for the purposes of saving duties and sales taxes. The consumers have been the principal losers of such decisions.

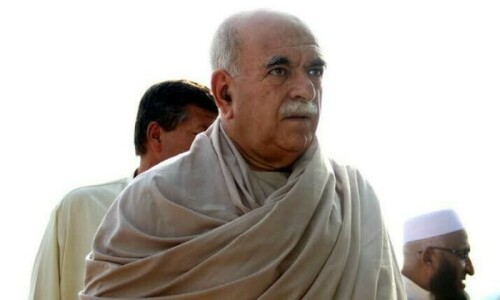

The writer is the Vice Chancellor of Beaconhouse National University.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.