Destination: Pakistan

"Adios Iran, Hola Pakistan" This was the update on Spanish cyclist Javier Colorado Soriana's Facebook page on January 20th, right after he crossed the Iran-Pakistan border into Balochistan. Pakistan only heard of him after an attack took place on his levies escort, killing six of the guards who were escorting him through Mastung. As the initial blame was placed squarely on Soriana's shoulders, many wondered what would possess a foreigner to rush in where even locals fear to tread. Well, the story's been through some changes since then, and may not be as open and shut as initial reports claimed. Kidnappings, killings and chaos … it's a wonder that Western tourists still pluck up the courage to visit Pakistan — and in fact travel through some of the most dangerous areas of this country. But they do, often armed only with decades-old guidebooks. Some are naïve, others passionate and determined, and some actually enjoy the thrill of journeying through what Newsweek infamously called "The most dangerous nation in the world". Here, we look at the experiences; some good, some bad and some life-threatening, that foreign tourists have had in Pakistan.

Put everything else on hold. Pack your bags and go see the world. You'll find a couch to surf on everywhere you go.

“Hello, is that Madeeha?”

“Yeah.”

“I’m at the railway station.”

“Who? What?!” I thought to myself. It was 8am, on a Sunday. I struggled to find my bearings and a reply.

And then it hit me: CouchSurfing Ambassador Ciro Rendes was to arrive in Karachi that morning. Paranoia kicked in.

“Where are you standing?”

“Near the main entrance.”

“Stay there, I’ll be there in 10 minutes.”

Rendes, originally from Lisbon, Portugal, is part of the CourchSurfing network of passionate travellers that seeks to build meaningful connections between globetrotters and local hosts. In its essence, CouchSurfing allows travellers to take a trip abroad on a budget, and experience authentic colours and flavours of the people they encounter on their journeys. Guests and hosts meet online, at the CouchSurfing portal. As a guest, you have to be on your best behaviour and as a host you have to make sure your guest is comfortable. Rendes was arriving to taste a slice of Pakistan; he was to stay with me.

My guest did not speak a word of Urdu, of course, nor was he carrying a mobile phone with a functioning Pakistani number. I was concerned for his safety, and rushed to the Cantt Railway Station.

But at the station, Rendes was nowhere to be found. I looked everywhere for him — inside the gates of the station, at the various teahouses and hotels to see if I could spot him sitting there, and I saw nothing. Afraid of asking people around me lest that bring too much attention to the fact that there was a foreigner lurking around, I eventually decided to call the last number I had spoken to him on.

At the office of the payphone service, I asked a smiling young man if a person who didn’t look like he was from “around here” had dropped by. The man excitedly responded, “You mean the boy with the really big bag?!” opening his arms wide to show exactly how ‘big’.

I couldn’t help but feel amused; backpackers, and the baggage they carry, aren’t a regular sight here. He told me that my guest was sitting next to the model train inside the station. Sure enough, I found Rendes there. On our way to the car, I noticed that most of the people in the area were smiling at us — they had known of his presence all along!

But Rendes was safe. He went to sleep on my ‘couch.’

***

Gizem*, a high-strung 47-year-old Turkish math teacher-turned-backpacker, was already in Karachi when I was introduced to her. She had travelled overland all the way from Antalya, Turkey to Karachi, Pakistan and planned to head to Lahore and subsequently to India. Barely fluent in English, communicating with Gizem involved a spontaneous potpourri of several languages as well as a lot of hand gestures and actions.

But Gizem was terribly clueless about the lands that she was traversing: having travelled from Zahedan, Iran to Quetta, Pakistan on a bus, she did not understand why Iranian authorities chose to delay the bus by three days, why there was a perpetual sense of foreboding in the air while travelling through the province, or why her hosts in Quetta asked her to stay mostly indoors.

All of that made sense when Gizem woke up the first morning on my couch. Adamant that she would travel by herself and refusing any help whatsoever, Gizem came up to me with a dingy old, yellowed guidebook in her hands. “No one seems to know where the Presidential Palace is!” she announced with great frustration, as she showed me a chapter of her travel guide titled ‘Sights to See in Karachi’.

Presidential Palace?

I took the book from her and saw that it had been published in the 1960s. And then I calmly told her that in 1969 the capital of Pakistan had been shifted from Karachi to Islamabad, and in 1970 the federal government had moved there. At that moment, it dawned upon me that Gizem was travelling through The Hippie Trail of the 1970s!

And yet, Gizem was one strong woman. During her stay in Karachi, she beat up a taxi driver for attempting to molest her, took a rickshaw all the way to Hawks Bay and even bought her own ticket to Lahore from the railway station.

Of course, she always had a couch to surf on in Karachi. She was always welcome at my house.

***

The most apt description of Way C., a Brazilian of Taiwanese descent, is that of a “trouble magnet.” Everywhere he went in Karachi, he was greeted by danger — Way C. had arrived in Karachi with hopes of having an “exciting time”, and that is precisely what he got.

We were en route to some salt works, driving merrily on Mauripur Road, when out of the blue, a group of women descended on the cars on the roads, slapping them and asking drivers to move out of the way. Within minutes, an entire neighbourhood from Lyari was out on the main road, with men, women and children carrying whatever they could and running for it.

Turns out, there was an operation taking place in that particular neighbourhood. Between the law enforcement agencies and the people they were after, common citizens did not feel safe. We managed to find a way through the fisheries and drove straight out into Clifton, where we stopped to catch our breaths, have some juice and process what just happened.

By the time Way C. went to sleep, he had already jotted down his exciting experience of the day. By the time he’d leave Karachi, he had many more entries to make in his journal. CouchSurfing had introduced him to the “real” Pakistan.

From gliding over glaciers to getting a blissfully agonising massage from a Lahore pehlwan, this unreluctant tourist is no stranger to the Land of the Pure.

For the third time in the past nine days, I say goodbye to Karimabad, Nagar and its four 7,000m mountains, which I now know like the back of my hand. I had planned to discover some new treks and thus be able to attract tourists to Hunza even in winter time. But in order to stay longer in the North, I must first get a visa extension, and that too from Islamabad or Lahore.

But to reach Islamabad or Lahore, I have to use the Karakorum Highway. Problem: the highway is shut for security reasons. The Gilgit office, two hours from Karimabad, can only grant an extra 15 days. So for those wishing to stay longer in Hunza, they must endure, in the best-case scenario, a gruelling 24 hour ride in a bus. Back and forth.

En route, I stop in Chilas, Dasu, Besham and Manshera to change from one local bus to the other. Another two times, stoppages are enforced: once due to a puncture, and the second time, due to an overheated engine. That people even in “wild” Kohistan and especially my different travel companions take more care of the only ‘Angrez’ than of themselves is so familiar to me that I nearly forget to mention it here.

When I arrive at three in the morning in Mansehra, the police take over the ‘look after the gora’ department. They say something about a strike across Pakistan, and that they will escort me to the bus station in Abbottabad, for my own security. Eventually, they put me from one police car to another until I was in Lahore.

Now this really isn’t part of the official duties of the Pakistani police, and I certainly tried to get them to not take such pains over me. You already know the image of the Pakistani police: according to a human rights report, the Pakistan police is the most corrupt institution in the country. But I witness another side of that coin: of overworked people who spend more time in their police cars than at home. I see people with monthly salaries of Rs12,000, who suffer poor working conditions, endure danger, are hit by load-shedding, inflation and uncertainty – just to provide a better future for their children. I laughed with these people who were able to make jokes about themselves, who know that corruption is one of the biggest problems in Pakistan, who know about their own bad reputation. I met Pakistanis.

Two days later, I lay in the sand pit of a courtyard in Lahore. The morning haze adds a pretence of freshness to the otherwise polluted air. One pehlwan (wrestler), smeared in oil and sand, stands on my back and another on my calves; something like an after-workout massage. While I am torn between smiling and screaming, another pehlwan is walking up and down the akhara with a 60-kilo iron tube around his neck. The khalifa is busy in the moment: he is playing with his five-year-old daughter. Next to me lay another pehlwan; an old man in a pink shalwar kameez is standing on his thigh.

After the massage, I feel like a newborn baby, happy to still be in one piece. I sit with the other pehlwans, drinking the traditional protein shake Sardai with them. They come from all walks of life: students, factory workers, small businessmen, all with familial responsibilities. In this moment, they are all the same, part of the family of pehlwans, part of another amazing piece of culture to discover in Pakistan.

The next day, I meet a French teacher who fell in love 39 years ago with a Pakistani woman and is now running a school for impoverished children. His aim: “We don’t want to teach the children only to read and write; we want to teach them what it means to be a citizen of Pakistan.” He speaks breathlessly, without full stops and commas. He tells me about Pakistani tourist attractions off the beaten track: the 9,000-year-old settlement of Mehrgarh and other archaeological sites of global importance, many of which I had never heard of. Then he talks about Sufi shrines, every one of them a world of its own and a thousand of them all over Pakistan. By the time he moved onto the Old Fort of Lahore or the Shalimar gardens, my mind was, as they say, blown!

Ah, and my visa extension? I applied for two months but was only given a month; Pakistan’s visa rules dictate a tourist can stay for six months per year in Pakistan. I was told by the visa office to extend the visa further in Gilgit where I had already sought my previous extension of 15 days. But this isn’t a complaint; last year many other tourists I had met didn’t get even a month-long extension while I got two extensions in a month! Instead, this is a plea: don’t let the few foreign tourists here pay the price for a person like Raymond Davis.

So I was unable to go to Hunza this year, because after another two bus rides along the Karakorum Highway in the next weeks I just don’t have the heart. Why is that, you ask?

Last year, even the best mountaineers in the world who conquered K2 – technically, the most difficult 8,000-metre peak – would rather wait three weeks for a flight out of Skardu, than suffer a 29-hour ride on the Karakorum Highway.

When I was at Borith Lake in Upper Hunza, I met many people from Lahore, Rawalpindi and Karachi. While they were always surprised to see me, when I heard how they had got there, I was equally astonished! “You sat through a 52 hours bus ride from Karachi, or 29 hours from Pindi only to spent four days here in Hunza? You are really brave, you are the real heroes!”

Gilbert Kolonko is the author of Let’s Go to My Favourite Travel Country — Let’s Go to Pakistan a German-language travel book on Pakistan’s Northern Areas.

Before the deadly attack on trekkers at the Nanga Parbat base camp last year, in which nine foreign tourists were killed, the glaciers and peaks of Pakistan were a major draw for adventure-seeking foreigners. Zaheer Ahmed recalls a trip taken with two American mountaineers who were more at home in the heights than he was.

They have a dream in their eyes, these two goras I’m accompanying. They have set their sights on a legend that now looms before us. It is the Latok peak, a rocky mountain that stands some 180 kilometers beyond Skardu on the Choktoi Glacier and 120 km west of the famous Baltoro Glacier. This peak is one of the most difficult climbs in the world and has yet to be successfully attempted from the Northern side. More than 20 expeditions have tried and turned back.

And now, Josh Wharton and Nathan Opp wanted to succeed where others have failed.

With a stiff and tall frame, short light brown hair and stern looks, Josh Wharton, the team leader, was dressed in a light-half sleeve shirt and a pair of shorts and slippers. Much taller and leaner, with long unruffled brown hair and a goatee, Nathen Opp, the other member of the team was dressed in a black long-sleeved shirt with shorts and a shabby pair of joggers.

This was Josh’s fourth visit to Pakistan – all previous visits had also been to scale Latok, a mountain that had become something of an obsession with him. Earlier he came here in 2009 with his wife, Errin, but didn’t succeed in summiting this coveted peak. Josh is a professional climber who works for Patagonia, a mountaineering company in the American state of Colorado. He has won the Ouray Ice Festival Mixed Climbing Competition consecutively for three years -- in 2009, 2010, and 2011. In short, he knows what he’s doing.

Nathan Opp, who hails from the American state of Montana, is also a professional mountaineer as well as an avid skier. In fact, he even brought his skis along for this expedition.

Four other members were to be part of this group but they backed out at the last moment.

As for me, I wasn’t there for the climb at all. I’m the Liaison Officer (LO), you see, and it’s my job to make sure that our foreign friends have as comfortable a time as possible. And so, the base camp was as far as I was going to go. But, as they say, it’s about the journey, not the destination.

And what a journey it was. Nanga Parbat was on our right and K2 on our left as our plane descended over Skardu city.

All the expeditions undergo various security clearances once in Islamabad, and later in Skardu, and it is the LO’s job to make sure this happens.

From there it’s a partly smooth and partly bumpy jeep ride to Askole. The bumpy part starts at Shigar, which along with being home to the famous Shigar fort, is also the last major town on the way to Askole. The metalled track then turns into a rough jeep-able trail with streams gushing down all throughout it. It’s a land of abundant apricot trees and on the left of the road flows the river Indus, swollen by the melting ice of the glaciers.

The long and vast valley of Skardu tapers off when one reaches Dasu — a small town where the vehicles stop to get registered at military and police check posts. Then there’s a terrifying moment as your jeep passes over shoddy wooden suspension bridges and your life, quite literally, hangs in the balance.

From Askole the climbers start acclimatizing themselves as they prefer staying in their tents than in hotel rooms. And then the hard part begins: a four-day trek from Askole to the Latok 1 base camp in which we had to walk on two glaciers, Biafo and Chaktoi. It’s tough, but it’s beautiful and we had plenty of candy to counter the sudden drop in blood sugar that walking at these altitudes causes.

As the altitude increases, so does the difficulty. There are places to rest, and places where taking another step seems impossible.

For the last day’s trek, one needs to start earlier as it is entirely a walk on the glacier. The higher the sun goes, the more the snow melts, resulting in boggy patches. It is a true test of nerves and endurance, as the glacier is a cascade of small ridges with long patches of ice, on which one easily slip.

Latok, with a height of 7,145 meters (23,600 feet) can be clearly seen from the base camp with its North western side towards us. Steep and tall was this unclimbed side of the mountain. Close to us was a camp of Bulgarian climbers who were also here to scale the heights.

It was Josh Wharton’s fourth and final attempt at this peak, and sadly it did not end in success. Nathan opted out and decided to return to the US, fearing that the climb was too risky. While he was upset with this decision, Josh decided that a solo climb was too dangerous and instead chose to attempt the Middle Sister, an unclimbed 5,800 meter rock spire a few hours from the base camp.

Now, you may have gotten tired just reading the story of this trek (and believe me there’s a lot that has been left out) but here’s the point: most of us Pakistanis have never even heard of these places, but here you have people from all over the world who have made climbing these peaks their ambition in life.

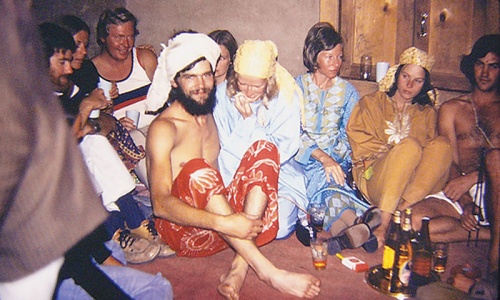

In the first three months of 1974 alone, over a million hippie tourists passed through Pakistan.

Between the late 1960s and the late 1970s Pakistan became an important stop-over on what came to be known as the ‘Hippie Trail.’

As a new generation of young middle-class Europeans and Americans began rebelling against things like the Vietnam War, the so-called ‘American Military-Industrial Complex,’ orthodox religions and against what they thought was the ‘tyranny of middle-class morality,’ many of them also decided to travel to lands they thought were still untouched by the soulless ways of industrialisation and capitalism-driven modernity.

The post-World War II economic boom in (Western) Europe and the United States, plus the fact that enrolment in universities and colleges in these countries saw an unprecedented increase during this period, saw the youth (perhaps for the first time) become more vocal and influential in impacting the politics and culture of their countries.

The flourishing post-War economics and subsequent lower costs of living allowed huge numbers of young middle-class Americans and Europeans to demonstrate their revulsion against the ‘straight society’ dominated by their parents, and live outside the confines of such a society.

This was done in various ways, such as through forming and living in leaderless communes in deserts and in abandoned buildings in the cities; or by getting involved in radical civil rights and far-left causes and politics that were not only furnished and expressed through political rallies and action on campuses, but also through experimental and more socially-conscious arts (especially music), and mind-altering drugs like LSD and cannabis that were believed to have given the users a unique insight into the workings of the mind, the body and society.

- Photo from the official Hippie Trail facebook and Flickr accounts.

Student/youth radicalism soon became a universal phenomenon. But whereas, for example, in countries like Pakistan, this phenomenon’s political aspects rapidly developed in the late 1960s, its social, cultural and aesthetical dimensions did not fully arrive till the early 1970s.

Apart from the universal proliferation of the products emerging from the arts of the phenomenon — such as music, films and the flamboyant fashions that reflected its ‘freewheeling spirit’ — another major way the social and aesthetic dynamics of what was taking place in the West made their way in Asian countries through the Hippie Trail. Some of the most prominent characters in this regard were the hippies. These were young college/university-educated Westerners who had decided to abandon the religions, politics and economics of ‘the straight society’.

One of the ways they did this was to physically move out from their countries and head for places they believed were unsoiled by the ‘soulless’ fall-out of things like materialism, organised religion and capitalism.

Some headed for countries in Africa, but most headed out for South Asian countries like India and Nepal. And they did so not by using air travel and then staying in established hotels (like conventional tourists). Instead they used a curvy overland route first charted in the mid-1960s by some proto-hippies. On this route (the Hippie Trail) they travelled in large groups in rickety buses, cheap cars and on motorbikes.

The route began in the Turkish city of Istanbul where the hippies from various West European countries and the United States would gather. From Istanbul they would drive down to the Iranian capital, Tehran. From Tehran the route would curve into Afghanistan. From Kabul it would then stretch to Jalalabad from where it would straighten and enter Peshawar. From Pakistan the hippies would then enter India and from India into Nepal.

The traffic on the Hippie Trail peaked in the mid-1970s, and along the way numerous cheap hotels and restaurants sprang up, creating a bustling economy across the route, tightly tied to the lifestyle of the hippies.

When the Trail entered Pakistan from Afghanistan (through the Khyber Pass) the travellers would stay a day or two in the city of Peshawar.

They would then travel down to Rawalpindi and from there head down to Lahore. After staying for few days in Lahore, some would cross into India through the Wagah Border, while many would head up to places like Swat and Chitral. A large number of the bohemian travellers would also make their way down to the sprawling metropolis, Karachi, before heading back to Lahore to enter India.

That’s why cities like Peshawar, Lahore, Swat, Chitral and Karachi saw the rapid emergence of numerous cheap hotels in the early and mid-1970s. In Karachi most of these hotels came in the Saddar area. Also, the many shops selling snacks and colas in the small shanty settlements that one drives through on the way to three of the city’s most famous beaches, Hawks Bay, Sandspit and Paradise Point, first began to emerge in the 1970s.

They mostly catered to the hippies and their eventual Pakistani contemporaries, selling them crates of soft drinks, Pakistani beer, snacks and (more discreetly) hashish, which the visitors took with them to the beaches.

According to the 1975 statistics of the Pakistan Ministry of Tourism (that was formed during the Z.A. Bhutto regime), in the first three months of 1974 alone, over a million hippie tourists passed through Pakistan. This was most beneficial to certain sectors of the economy that included second and third tire hotels, roadside restaurants, outlets offering tour guides and shops dealing in Pakistani ‘folk clothing’ and artefacts.

For example, Karachi’s famous Zainab Market first began to take shape during the said period. And even though for almost two decades one has struggled to spot a foreigner in this market, yet, in the 1970s, more Westerners were seen here than the locals.

Also interesting to note is the fact that young European and American visitors in their colourful hippie attire were a common sight even in the tribal areas of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and in Balochistan towns, such as Sibi, Quetta and Ziarat. Many of these places today have become ‘no-go areas’ even for Pakistanis.

The traffic on the Trail began to recede in 1979. After that year’s Islamic Revolution in Iran, Tehran stopped being a stop-over on the Trail. Then, in December 1979, when Soviet troops entered Afghanistan and triggered a civil war there, Afghanistan too fell off the famous overland route.

But Pakistan remained on the Trail despite a military coup here by a reactionary military general in July 1977. However, with Iran and Afghanistan gradually falling off the Trail and then Pakistan entering the civil war in Afghanistan, it too fell off the route.

The Trail changed course and now stretched from Istanbul to India and Nepal through Iraq. But it disintegrated and finally vanished after Iraq went to war with Iran in 1980. Another reason was also the gradual receding of the hippie culture in the West and the United States that saw its politics move to the right.

The famous Lonely Planet series of travel books that have been hugely popular and one of the best-selling travel guides across the world ever since the mid-1980s, were first started on a small scale by a young American couple travelling on the Hippie Trail in the 1970s.

Travel books on Pakistan authored and published by Westerners were common in the 1970s and early 1980s. However, one has to struggle to find such a book today. The last Lonely Planet guide fully dedicated to Pakistan was published in the 1980s. The most recent one just has info on the Karakoram Highway.