Westernised transgenders or colonised transphobes? Examining the FSC verdict on the Transgender Rights Act

Hailed as one of the most progressive pieces of legislation internationally, the passage of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2018 marked a major milestone for the advancement of transgender rights in Pakistan.

Summarily, the Act prohibits discrimination against a transgender person in areas such as education, employment, and healthcare. It directs the central and provincial governments to provide welfare schemes in these areas such as reforming health curricula to address basic health issues of the transgender and intersex community, besides other measures that ensure the full inclusion and participation of transgender persons in mainstream society via rehabilitation, vocational training, and employment schemes.

Under the Act, offences such as compelling or enticing a transgender person to beg or enter forced or bonded labour, denying a transgender person the right of passage to a public place, forcing or causing a transgender person to leave their household or village, harming or endangering the life, safety, health, or mental and physical well-being, and physically, sexually, verbally or economically abusing a transgender person are punishable offences.

Many stakeholders, ranging from community activists to human rights experts, lawyers and medical professionals, joined hands to develop this legislation. It is based on the most recent research while also being culturally specific to the khwaja sira communities that have existed for centuries in Muslim South Asian society.

In contemporary Pakistan, the transgender community has been marginalised because transgender people don’t ‘fit into’ existing gender categories. Consequently, they face problems ranging from social exclusion and discrimination to lack of education, unemployment, and adequate medical facilities.

The 2018 Act recognised this status and gave it legislative backing to begin solving issues affecting the transgender community, ensuring access to healthcare, education and self-determination and recognising their right to human dignity.

A (100) step(s) backwards

The harassment, violence and discrimination faced by the transgender community in Pakistan has been co-opted by conservative groups in a bid to ostracise and demonise a community with a rich history and cultural identity in the country.

The hard-fought gains for legal gender recognition that culminated in the passing of the 2018 Act are at risk of being reversed based on stereotypical and harmful views and insidious misinformation campaigns. These sensationalist claims, and the false conflation of a person’s real or perceived gender identity with sexual orientation makes transgender persons even more vulnerable to abuse by law enforcement, harassment, arbitrary arrest, and prosecution.

On May 19, 2023, the Federal Shariat Court of Islamabad (FSC) announced its verdict on 12 Shairat petitions through which several petitioners challenged various sections of the Act. It ruled that sections 2(f), 3 and 7 of the Transgender Act 2018, which relate to gender identity, the right to self-perceived gender identity and the right of inheritance for transgender people do not conform with their interpretation of Islamic principles. The entire khawaja sira community is mourning the FSC’s attempt to delegitimise the Act — which is already resulting in more violence and hatred towards their community.

The petitioner’s ‘concerns’

It is unfortunate that the colonial legacy of ‘Hijra panics’ continues in South Asia to this day. Many of the concerns or panics expressed by petitioners and opponents of the Act echo right-wing Western anti-trans narratives in Pakistan and this is only a growing trend.

Fundamentally, the petitions expressed concern over the anglicised words ‘transgender’ and ‘intersex’, and the right to self perceived identity. The concerns extend to hypothetical scenarios that may result if ‘people begin changing their gender identity at will’.

Kamran Murtaza, a senior advocate at the Supreme Court of Pakistan appeared on behalf of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam Pakistan to present their arguments. He stated: “Any biological male person can get access to all the places which are secluded specifically for female genders, like girls educational institutions, schools and universities etc., girls’ hostels, hospitals and other places, where services are provided to women only. Similarly, the services and jobs, which are specially and specifically allocated to females can easily be misused by biologically male persons having a CNIC of ‘X’ gender mark issued by Nadra identifying him as a ‘transgender woman’ under this law, because by doing so, that biological male person cannot be stopped [from] avail[ing] any facility or privilege meant for women only.”

Another concern was “biological men/boys” competing with girls/women in the same categories and “outperforming them in every sport”. This discourse is prevalent in the west, and is barely a concern in our local context.

Khwaja siras are not asking for access to spaces where only women or only men are allowed — they are asking for their own third spaces, an X on their ID card. While the 2018 Act was written on the basis of research, evidence, and lived experience — the concerns that motivate the FSC ruling are not.

Doctors and professors from the Pakistan Islamic Medical Association also stated that “now some new terms like ‘other-kin’ and ‘trans-species’ are also being introduced which are more disturbing than the term transgender. If any society accepts the concept of transgender, as stated in the impugned law, then there will be nothing to stop the sexual perversions and sexual degeneracies spreading in the society.” It is to be noted that no such terms have been used in the Transgender Act — such concerns are speculative projections of fear that are not grounded in the lived realities of khwaja siras in Pakistan.

During the delivery of the verdict, the court speculated that the Act could lead to rape, and sexual assault of women as petitioners alleged that it makes it easy for a man to gain access to “exclusive spaces” intended for women, “disguised” as a transgender woman.

Interestingly, the petition that raised this concern cited four instances of sexual violence by transgender women against cis-gendered women and minors. All four cases were from the United Kingdom. There is no publicly available evidence of such incidents taking place in Pakistan. Not to mention, looking at the proportion of perpetrators from male, female and transgender would do one some good. Individual cases of violence are often disproportionately highlighted and used to spread narratives about entire communities. This is not only the case with transgender communities, but all marginalised communities across the world, including Pakistanis and Muslims.

If the FSC is concerned with the rampant violence against women that already exists in our society, scapegoating our already marginalised community will not improve the condition of women in Pakistan. Women are being raped in public parks, on motorways and in their homes. The FSC should start a separate inquiry into this fahashi if it is concerned with the violation of women in this country. Instead, the state has failed to provide women with safe women-only spaces or safe public spaces. It has also, at times, failed to condemn or convict male perpetrators of violence, even when the evidence could not be more obvious.

Moreover, khwaja siras and transgender persons are not asking for access to women-only spaces; this is a myth designed to aggravate our population against the community. We already exist in this society and have co-existed for centuries before. Denying our humanity will not make us go away, it will only make our lives harder and deny the human dignity we too have a right to.

Speculative and panics of a disproportionate level were stark in many of the petitioner’s statements, as was also expressed by Amnesty International: “This ease of changing the identity will pose a threat even to the national security in certain cases … This “facility” will provide the criminals, terrorists, spies and refugees a camouflage to hide their identity, which may create a serious problem in anti-terrorist activities in the country.”

A big price to pay

A major concern was also the issue of inheritance. According to them, a biological woman can change her gender identity to a man if the Act is implemented and gain access to a man’s share in inheritance (as set per Islamic law). Ironically, they fail to recognise that the opposite would result in a trans woman losing share in inheritance. Furthermore, they fail to recognise the discrimination faced by the community, for which an added share in inheritance would be a far-from-substantial reward.

In response to the Act being misused, Advocate Farhat Ullah Babar pointed out, “A law is liable to be misused particularly if it [offers] special incentives to persons addressed in the law. The Transgender Protection Act 2018 confers no special privileges on transgender like reserved seats in parliament, in professional colleges etc. The 2018 Act only gives the transgender persons basic human rights available to every citizen including the right to vote, to contest elections, to seek education etc…

“Secondly, is it conceivable that anyone will willingly want to be recognised as a member of the most dispossessed, the most vulnerable community whose members are threatened, intimidated, ridiculed and harmed on a daily basis?”

Precedents from the (Islamic) world

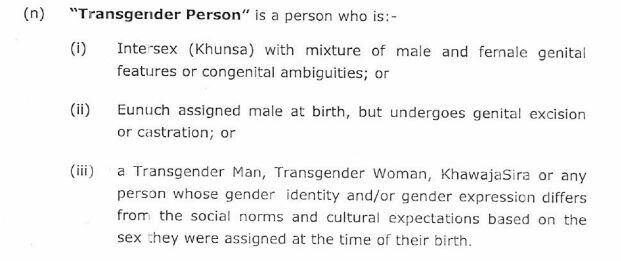

Specifically, Section 2(n)(iii) of the Act has been rejected by the FSC based on their own interpretations of how gender works — the court insists that gender must conform to biological sex. Ansar Javaid, petitioner and chairman of the Birth Defects Foundation called gender dysphoria a “curable disease”.

This claim flouts the reality now accepted by medical and legal communities within and outside Islam, that sometimes it simply does not. How can we progress as a nation when we do not accept the lived realities of our own citizens?

International medical and legal guidelines call for accommodating sexual differences as essential to establishing ethical standards regarding the treatment of the human body. Muslim-majority countries started to allow for the change of legal gender, with the case of the Turkish Civil Code in 1988. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini gave approval for sex reassignment surgeries in 1964 and again in 1985. Sex reassignment surgeries have been conducted in Morocco since 1956 and the first one occurred in Egypt in 1982. Even our own laws set a better precedent than this, such as the 2011 Supreme Court decision to grant voting rights to khwaja siras which was won by an attorney specialising in Islamic law.

In 2019, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared that “gender incongruence” or gender dysphoria will no longer be considered a behavioural or mental disorder. “It was taken out of the mental health disorder because we had a better understanding that this was not actually a mental health condition and leaving it there was causing stigma,” said Dr Say, a WHO reproductive health expert.

Myth vs fact

As mentioned earlier, misinformation and conflation with western politics has led to a misunderstanding of the Act itself. Any claims that this law pursues an agenda of legalising homosexual relationships are false. The Act does not refer to sexual orientation or sexual relations at all. The preliminary objections to the petitions clearly state: “The entire text of Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2018 does not use any phrase or expression which may make reference to lesbians & gays or any other person who commits homosexual acts.”

Below are two more examples of some of the myths that are being spread by bad faith actors:

Myth: Someone may perceive themselves F (Female) or M (Male) contrary to the sex assigned to them at birth and get their legal gender changed to the opposite.

Fact: The transgender persons do not demand recognition as F (female) or M (Males). They only want to be legally recognised as X (transgender) for the purpose of accessing basic rights enshrined in the Constitution.

Myth: People in married couples will declare themselves the same gender as their spouse, or people of the same sex will get their legal gender changed to marry.

Fact: “This would automatically annul the marriage because the marriage can be registered in Nikahnama only between M (Male) & F (Female). There is no provision in any law and any rule for the registration of marriage between a X (Transgender) & M (Male), or between X (Transgender) and & F (Female) or between X and X,” Advocate Farhat Ullah Babar explained.

Amnesty International and other human rights groups have directed that removing the section in concern from the Transgender Act would reverse essential protections and must not be accepted.

The Government of Pakistan must not forget that it is its duty to uphold and protect the rights of all people, regardless of their real or perceived gender identity or gender expression. Its failure to do so will result in them being in violation of their obligations in respect to local legislation as well as international human rights law. Moreover, rights groups have also said that the government must stop any attempt at amending the Act that would prevent transgender persons from obtaining official documents that reflect their gender identity without complying with abusive and invasive requirements like medical examinations.

The FSC’s decision on the Transgender Rights Act will not take legal effect immediately. The Constitution clearly states that this court’s decision on the repugnancy of any law to the injunctions of Islam, will have no legal effect until the time period specified for an appeal has elapsed. The federal and provincial governments have six months to lodge an appeal. Until that time has passed, the court’s decision should not be deemed to revoke the khawaja sira community’s existing rights under the Act.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.