The state wants to make Karachi a 'world-class' city. But what's the cost?

For a vast majority of residents in Pakistan’s cities, the process of accessing and holding on to space for shelter and for work has become a struggle to endure in the face of profound uncertainty. I am referring here not only to the poor, but also to those residents who don’t fit into neat classifications of poor or middle-class; residents that some scholars have called the "in between".

They share certain similarities in terms of how they manage their housing and livelihoods needs; they are increasingly susceptible to changing prices of inputs and especially to unexpected shifts in rents and land tenure arrangements. These residents represent a heterogeneous mix of vulnerable lives: from salaried government employees, shopkeepers and small-scale entrepreneurs to technicians, repairmen and service and industrial workers, to name a few.

Their purchasing power appears to be declining and they are constantly struggling to find ways to stretch earnings by supplementing primary incomes.

Special report: What does the future hold for Karachi's historical Saddar area?

In our ongoing work at the Karachi Urban Lab on displacements and the violent reconstruction of Karachi’s central districts, my colleagues and I have been observing how these residents are being rewritten into the city’s narrative as ‘encroachers’ and/or ‘illegals’.

From metropolitan centres like Karachi, Islamabad, Lahore and Peshawar to non-metropolitan regions such as Mithi and Islamkot, an onslaught of Supreme Court-backed ‘anti-encroachment’ drives to clear footpaths and streets and to reclaim government land has triggered widespread evictions and demolitions of shops, markets, houses and informal spaces of shelter.

These actions have impacted mostly those lives for whom the city has been a space for carving out a viable life. In this moment when ‘encroachers’ are perceived as a problem that must be solved, Pakistan’s cities have become war zones: half-built and half-destroyed terrains of spatial restructuring.

Livelihoods, loss of work

In the county's largest metropolis, Karachi, the eviction and demolition operations against commercial units have been supported by multiple stakeholders: from provincial and district governments, including municipal committees and utilities, to the paramilitary Rangers and the police.

The violent exercise of state power with its uneven effects has been justified in a bid to reinstate a well-ordered and unhindered urban environment that is acquiescent to the rule of law.

Last November in Karachi’s historic quarters, 1,700 shops were demolished and countless street vendors and hawkers removed from the Empress Market. These actions have paved the way for the market’s reconstruction. The demolitions also extended into adjacent areas of Saddar with nominal relocation provisions for the displaced. For over 50 years, these markets have been a vital space for 4,000 hawkers to secure their livelihoods, an economic practice that has also sustained thousands of households.

In-depth: What are the consequences of the anti-encroachment drive?

The reconstruction of Karachi’s historic quarters is aligned with city-wide growth strategies that emphasise aesthetic value and aim at promoting a tourist economy by converting select cultural heritages into urban amenities. These growth strategies also tap into the aspirations of upper-middle-class audiences, especially their anxieties about hygiene, cleanliness and order. Local state officials and even representatives of the judiciary have routinely invoked the city’s historical imagery as an aesthetically acceptable model for urban reconstruction.

Even though heritage preservation plays an important role in the promotion of the urban tourism industry, I remain cautious given its impact on poor and low-income residents/workers who are often driven out; for instance through evictions or rising rents as profit-seeking capital investment takes over these spaces.

To date, nearly 11,000 shops and 20 markets have been demolished in the anti-encroachment drives in Karachi’s central districts. But it isn’t just shopkeepers and traders who have incurred financial losses; the losses extend to wholesalers, service contractors, transporters and workers, many of whom have seen their livelihoods evaporate in the war zone's wreckage.

Yet, the evictions story is far from over. Municipal authorities intend to further demolish 2,000 shops and stalls, for instance the 40-year old Urdu Bazaar Market and the Lea Market (see the map below).

I am uncertain how many livelihoods will be impacted because of this eviction. Suffice to say, municipal authorities have not shared with the public any plans to relocate those who are going to be displaced.

For decades, shopkeepers, traders, hawkers, small-scale entrepreneurs and networks of ancillary workers and suppliers have accessed and held on to these work spaces by relying on a form of legitimacy that was based on striking deals with municipal authorities, the police, military and politicians for leases and rents. These ‘quiet deals’ conferred a distinct legitimacy in which the state transgressed the rule of law by circumventing accountability and planning regulations.

This ‘illegality’ has underwritten the mode of governance in cities like Karachi, a process through which the state has accommodated and tolerated urban livelihoods and survival strategies — whether on the city’s footpaths or as commercial unit extensions on government land.

But today, the judiciary’s interventions into urban planning and local government imply a shifting terrain of governance and power; a process of intensifying evictions and demolitions with little or no resettlement or compensation.

Ironically, the mayor’s office has been beleaguered by the mass wreckage left behind. Who will get rid of the ruins? Over the past few decades, financial austerity and limited resources have forced Karachi’s municipal authorities to rely on a complex web of third-party contractors who supply not only the bulldozers and loaders but also the men who drive them.

Bahria Town Karachi: Greed unlimited

In the absence of reliable manpower and equipment for clearing the wreckage, the mayor has turned to his own network, notably the real estate tycoon Malik Riaz who has supplied the requisite equipment.

The irony is not lost: in Karachi’s periphery, the construction of Malik Riaz’s colossal gated community project — Bahria Town — materialised through illegal deals struck with state officials for land acquisitions that led to the demolition of villages, loss of livelihoods and impacted local ecologies.

Effects on formal & informal housing

As evictions and demolitions gather pace in urban centres, residential spaces are also affected. In Karachi, it isn’t just residents in informal settlements that are the target of evictions; for instance the informal settlements that include the 28 neighborhoods situated along the Karachi Circular Railway (KCR) tracks and nearly 1,400 households that were displaced and resettled on amenity plots in North Nazimabad due to the Preedy Street’s reconstruction in 2008. The latter group now confronts the nightmarish prospect of double displacement.

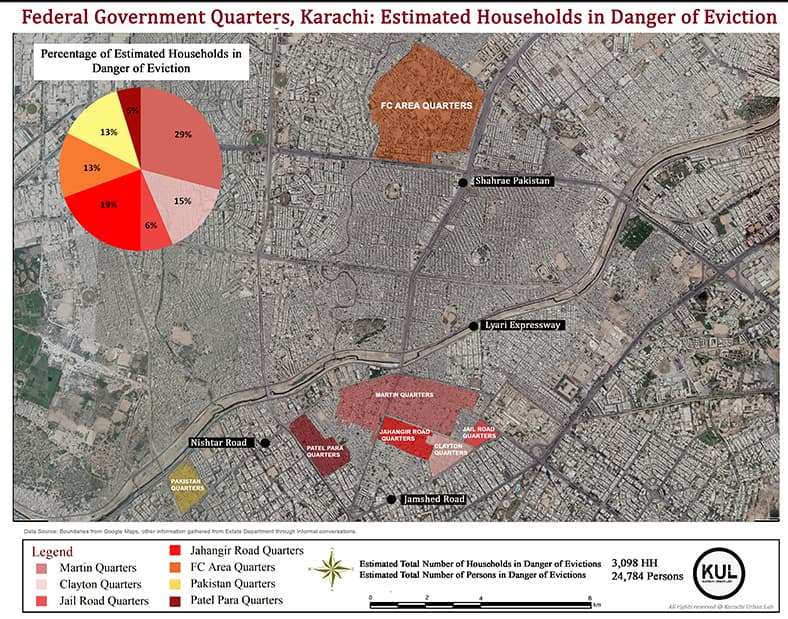

But also, planned residential spaces like the Martin Quarters where residents are employed in public and private institutions, such as government employees, software engineers, schoolteachers. Martin Quarters lies just beyond Teen Hatti, straddling both the PECHS and Garden East, and its central location marks this residential space as prime real estate.

It is part of seven government quarters (see the map below) where an estimated 24,784 residents face evictions due to the Supreme Court’s anti-encroachment notice. Many of the residents who have made home in these planned settlements came as refugee migrants during Partition. In October 2018, in an unanticipated eviction operation against Pakistan Quarters, residents blocked the entry of officers from the federal housing department, and were met with an onslaught of police batons and water cannons.

In the informal settlements situated along the KCR tracks, approximately 60,000 residents are in danger of eviction (see the map below). Who are these residents? They are recyclers who sort rubber, plastic leather, shoes; drivers, labourers, shopkeepers, security guards, housewives, cattle farmers, tailors; maids who work in Karachi’s upper-middle-class homes; and an emergent generation of teachers, bankers, technicians, lawyers.

As the federal government pushes aggressively for the revival of the KCR project with no resettlement plan in sight, residents in Ghareebabad in Saddar Town; Umar Colony in Jamshed Town; Quaid-i-Azam Colony in Liaquatabad Town and Machar Colony in Keamari Town, to name a few, are living in a constant state of anxiety.

Life along KCR: Between aspirations for mobility and threat of eviction

These settlements are also experiencing what I call ‘low-intensity’ demolitions. In such instances, municipal authorities don’t demolish the entire residential settlement as this would draw unwanted media attention given the ongoing controversy about resettlement plans. Instead, a few pakka houses and particularly jhuggies are destroyed.

Municipal authorities and the media continually refer to the jhuggie dwellers as khana badosh or vagrants even though these communities have lived in the neighbourhoods for decades.

In August 2018, in Ghareebabad Colony located next to the PIDC Bridge, five residential units were demolished under the pretext of repairing a water line. Approximately 40 people were displaced, and one person was forced to relocate his belongings to an empty space under the PIDC bridge, while others sought refuge in relatives’ homes.

For the federal and municipal authorities, the low-intensity demolitions signal that some progress is underway with the Supreme Court’s order. There is also a subtle expectation that residents will relocate without resistance when bulldozers arrive next.

Akin to many other parts of the city, the KCR informal settlements are mixed-use spaces: commercial and residential spaces where people live and work. In Quaid-i-Azam Colony, not only were extensions of houses located along the track demolished, but a longstanding and thriving furniture market was destroyed. In other settlements, countless small-scale mechanic repair shops, shoe recycling businesses, grocery shops, small-scale cattle businesses and recycled furniture warehouses have been razed.

These small-scale, informal economies of work are connected through the survival strategies of the poor and the urban majority; they symbolise what is essential for the ordinary citizen to belong in the city. The spaces denote the right to work that is also connected with the right to housing. It is interesting to note that in the broader anti-encroachment narrative, it is the poor and the urban majority’s work spaces that have the least legitimacy.

The chief justice’s reaction is telling in terms of the support given to selective uses of state power and violence in the anti-encroachment operations. After the violent standoff between the federal housing department officials, police and the residents of Pakistan Quarters, former Chief Justice Saqib Nisar reprimanded Karachi’s mayor. Shortly thereafter, the eviction deadline was extended.

Related: 'The woman was stricken as they demolished her house. She went into coma and died'

But the Supreme Court’s ambiguous language has enabled the municipal authorities, the Rangers, the police and their shields and batons to collectively ease the passage of bulldozers brought to destroy so-called ‘illegal’ spaces.

In a rush to demolish commercial units in the KCR’s dense informal settlements, the anti-encroachment drive has destroyed ground floor work spaces in mixed-use buildings. But this has left the upper residential spaces teetering precariously on shaky foundations. Thus, residential displacement has accelerated as families are being forced to vacate homes rendered dangerous for inhabitation.

In the context of the Supreme Court and government officials’ desire to return Karachi to its "original shape and colours", the situation for street vendors, small-scale informal businesses and shopkeepers appears to be more precarious as they are continually displaced without any plans for relocation.

In fact, municipal authorities are extending their remit to limit the activities of street vendors by blocking their access to urban spaces such as the Clifton Beach, which has been the penultimate public space for the poor and the urban majority.

Ultimately, the ongoing dehumanisation of informal workers and the increasing criminalisation of their work implies that they have limited or no institutional channels to turn to in order to claim their right to work. This contrasts even with some of the city’s informal residents who have been able to access institutional channels and political connections to resist evictions and claim their rights. For informal workers such as street vendors, hawkers, shopkeepers, recyclers, small-scale informal entrepreneurs, the situation appears to be the opposite.

The quest for an orderly city

In Karachi and in other urban centres across Pakistan, municipal authorities, mayors, commissioners, urban planners and privileged citizens are upholding a claim to a well-ordered urban environment where public space is unhindered by ‘encroachers’, thereby restoring the city’s splendour and also clearing the way for infrastructural developments.

In Karachi’s case, these claims also overlap with an irrefutably clear discursive and aesthetic form in the idea of a ‘world-class city’ that is tied to specific imaginations of improvement, transformation and renewal. To what extent have the poor and the urban majority been displaced from this development imagination? People are not only being displaced from their homes but also from their work spaces.

Also read: Who pays the price for mega projects in Pakistan?

As the ‘rule of law’ and a new urban planning regime reconfigure government and the urban environment today, it matters that we ask how this process is affecting urban spaces that have sustained the economies of everyday life and different forms of housing for the poor and the urban majority.

Why? Because people are not rendered vulnerable or poor naturally. Instead, they are pushed into precarious situations by ill-advised Supreme Court orders, top-down planning decisions and state violence that end up reproducing urban inequality.

We need urgent conversations about urban planning as a critical site of politics, especially one that advocates the right to an inclusive city. But we must do so by first acknowledging that urban planning has a dark side of control and violence, and the effects on cities in Pakistan are real for the poor and the urban majority.

I am indebted to the KUL research associates for their insightful comments on this piece.

Are you working on Pakistan's political economy and development? Share your insights with us at prism@dawn.com