In Balochistan’s Dasht, staying in school is an act of rebellion in itself

Every morning, as the sun rises over the dust-swept hills of Achanak Bazar in Balochistan’s Dasht tehsil, Shareefa wraps herself in a chaddar, gathers her four children, and begins the long walk to school. There are no schoolbags slung over their shoulders, no uniforms, no books — it is not the children who will sit in class, but their mother.

The journey starts from a mud-walled house in one of the area’s scattered villages, situated approximately 40 minutes from Turbat city. Inside a small classroom at one of Dasht’s last standing primary schools, Shareefa takes her place on the bench.

Her children roam freely in the schoolyard, tumbling over one another in games that sometimes erupt into fights. When one of them cries, she rises quietly, calms the chaos, and returns to her seat. The chalkboard has already moved on to the next math question. The teacher never questions the interruptions; she never needs to.

When Shareefa first arrived to enrol, she was clutching the hand of her youngest child, and carrying eight years of silence. She had dropped out after the fifth grade, not for lack of will, but because there was no schooling beyond that in her village. Girls like Shareefa, who could not afford to move to Turbat, stayed behind. Early marriage followed, then motherhood.

“If you allow a woman with four children, I will study,” she had said softly. The teacher nodded, and so began her second chance at life.

Life in Dasht

Tucked in the rugged terrain of Kech district in sourthern Balochistan, Dasht is a scattered region comprising several remote settlements, each more isolated than the other. The people here have long depended on farming, but the drying local dam has snatched that livelihood too. With water now rationed by number, farmers have to wait days for their turn, ultimately forced to give up altogether.

In search of work, many of them have crossed over to the other side of the border into Iran, while others have moved into darker trades.

But that isn’t all of what is plaguing Dasht. The area lacks fundamental infrastructure — schools, hospitals, clinics. In times of emergencies, there is nowhere to go. Literally.

“A [sick] person has to die in Dasht … or wait,” a resident tells Dawn.com. Pickups leave for Turbat only once a day, typically before 11am, and if you miss it, you wait another day. Those without a vehicle of their own have little to no choice.

However, what Dasht suffers from the most is addiction.

“Here, drugs are like sweets,” says Salma, a widow from Sangai Dasht. “Some powerful men come, ask our men to cut wood, and in return, they hand them crystal meth. That’s how I lost my husband. That’s how many other women are losing theirs.”

Hence, survival in the area often rests on the backs of women. They farm what little land remains, sew intricate embroidery for mere pennies, and walk miles to fetch water from deep, uncovered wells. There’s no reliable mobile network, no electricity, and the only internet is patchy fibre WiFi, accessible only to those who own farmland, not the families working it.

Amidst the mess, it is education that remains the most neglected.

According to the Economic Survey of Pakistan 2024-25, unveiled just days earlier, the country’s cumulative expenditure on education — including the federation and provinces — remains a meagre 0.8 per cent, with the literacy rate a little above 60pc. Balochistan tops all the provinces in terms of out-of-school children, with a majority of them being girls.

The condition of schools that do exist is a completely different issue altogether. The survey shows that Balochistan consistently lags behind when it comes to access to electricity, water facilities, and toilet access.

The education epidemic

“There is no schooling after the fifth grade,” says Sanji, a young mother. “Even that exists only on paper. Teachers take their salaries but never show up.” Salma scoffs, recalling the time when she tried to enroll her daughter in the sixth grade in Turbat. “They told me she’s not even fit for the first grade. And they were right. Our kids hardly see a teacher’s face. How can they read?”

At government schools in Dasht, if a teacher appears at all, they arrive at 8am and leave within an hour. There are no peons, no inspections, no accountability. “No officer has ever visited our school,” claims Sanji. “Why would they? They get paid either way.”

“Teachers who are posted here from Turbat often don’t come themselves,” she continues. “They find someone local, hand them half their salary, and never set foot in the school again.” The locals assigned in their place, she adds, have only seen a blackboard from afar. “How are they expected to teach?”

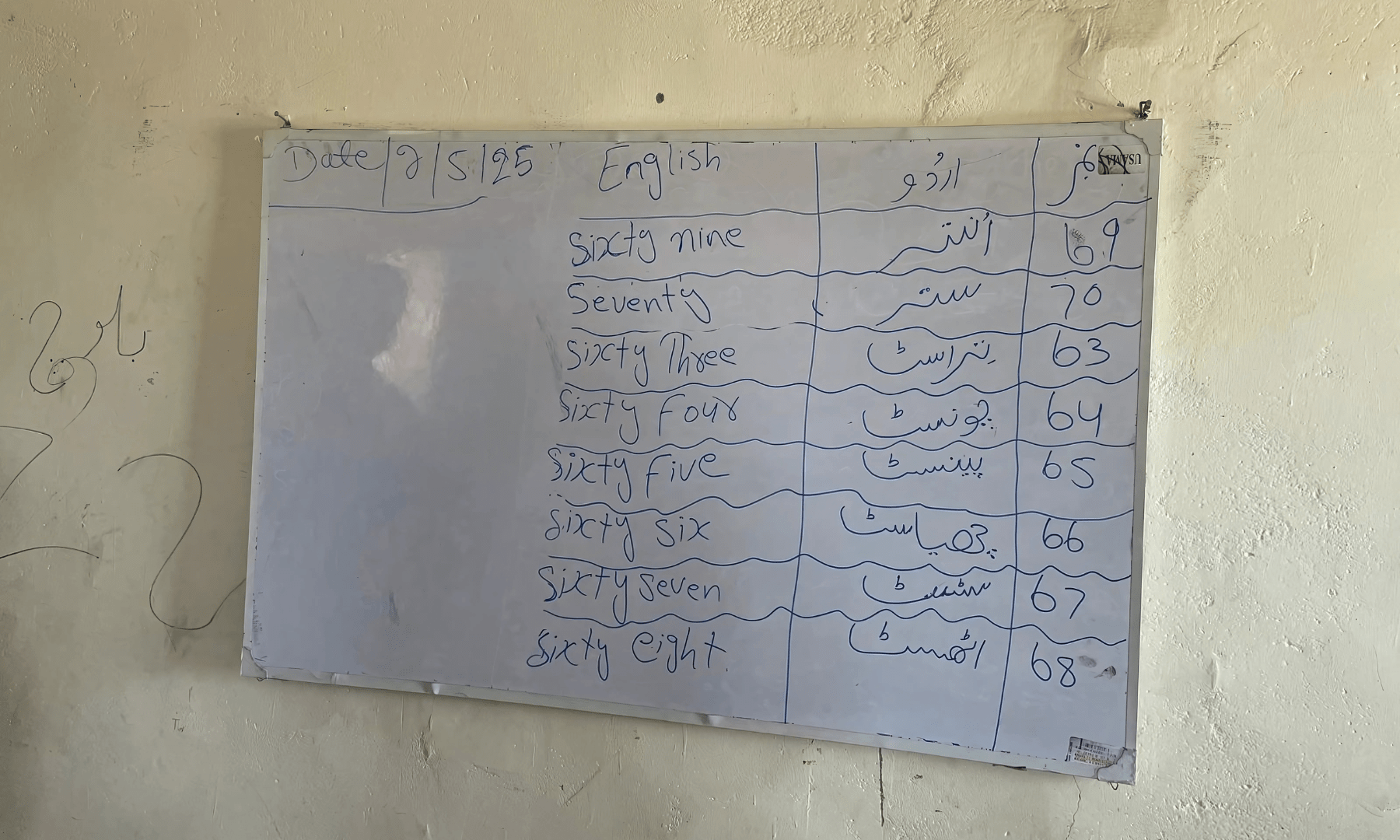

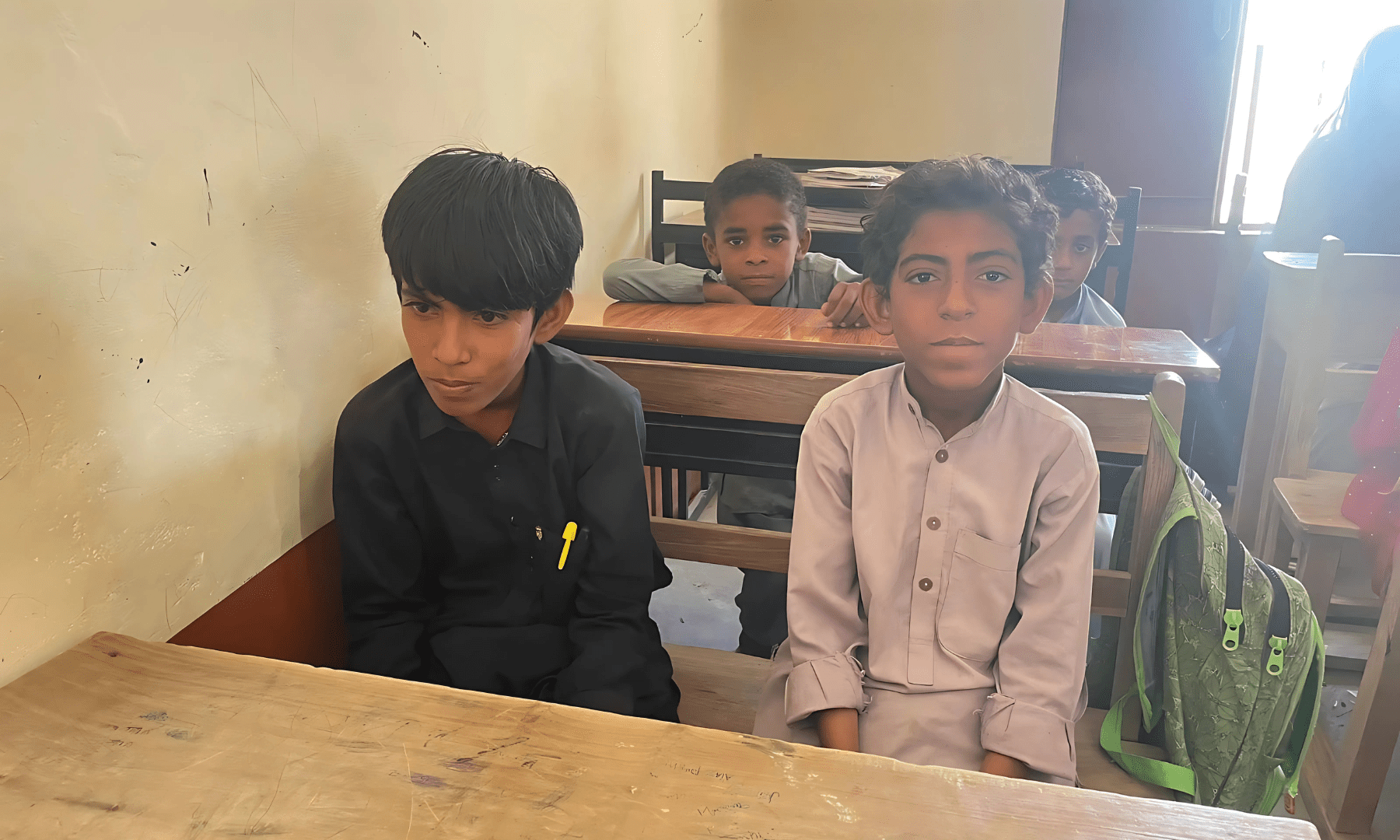

It’s in this forgotten stretch of Balochistan, where silence and survival go hand-in-hand, that a class of 49 students, ranging from 11-year-old boys to 25-year-old girls, have gathered under a short-term, accelerated learning project supported by Unicef.

The United Nations agency’s 18-month initiative focuses on providing access to education for out-of-school children through the establishment of middle-level Accelerated Learning Program (ALP) centres. They educate children who have either never enrolled in school or dropped out, enabling them to catch up academically and transition into the formal education system at the middle-school level.

According to Faiz ur Rehman, Unicef’s Kech district project coordinator, the programme was launched in Tehsil Dasht on March 12, 2025, with a syllabus designed by the Bureau of Curriculum, Balochistan. “It’s different from the regular classroom syllabus,” he noted, “and is specifically tailored for children aged nine to 15.”

A second chance

The class gathers each morning in the lone room of a crumbling government boys’ primary school in Kont-e-Dar, one of Dasht’s few remaining functional school buildings. Here, under one roof, students from four distant pockets of Dasht — Kont-e-Dar, Jangol ay Mehtag, Merani Dem Mehtag, and Achanak Bazar sit shoulder to shoulder.

Some walk up to 40 minutes on foot to reach the school. Boys often hop onto the back of passing pickups. Girls, in pairs or alone, walk dusty roads under the unforgiving sun — Kech is known for being one of the hottest regions in the province — with their books wrapped in cloth.

These long walks are not a rarity in other areas of Balochistan, where schools are few and far, with limited resources to reach them. The distances between settlements are vast. “In this heat, it feels like the head is boiling by the time we get to school,” says Ghani, a 12-year-old student.

“Whenever a biker or a pickup stops to give us a lift, it feels like the happiest day. When they don’t stop … we just send a pitiful curse their way.”

At the school, the classroom space is tight. The heat is unforgiving. There’s no electricity, no solar power. The washroom is nonfunctional. Children take breaks just to splash water on their faces before returning to class, their clothes soaked in sweat. The desks, small and few, strain to hold both the young boys and grown women. The students sweep the classroom floor themselves.

“Sometimes our hands ache,” says Shamsi, who just enrolled without ever having had a pause in her education, “but that doesn’t trouble us.”

“In winter, it becomes worse. When the cold wind hits us, we shake, we keep trembling. Sometimes, on our way, we stop at a villager’s kitchen just to warm up in front of the fire, and then go back to school… only to find the teacher absent,” she scorns.

But what now troubles them is something else entirely: the fear that this opportunity might vanish after 18 months. “What happens after that?” the children ask. It’s not a question about the syllabus. It’s a question about continuity.

For many in the room, this isn’t the first time their education has stopped, and they fear it won’t be the last. In most parts of Dasht, schooling ends at the fifth grade. The children who once dropped out for lack of options now fear another long wait. Another lost decade.

Sangeen, 22, sits at the far end of the classroom. A widow with no children, she walks nearly 30 minutes from Jangol Mehtag each day. “There’s nothing for me at home,” she says. “After school, I do embroidery to survive.” She had passed the fifth grade seven years ago. “I don’t know with what hope I’m studying now.

“Maybe just because they say education opens your eyes.” She pauses, then laughs. “But if this project ends, will I have to wait another seven years?”

Usman is 13, his skin sunburnt from days of walking under the scorching sun. A hat shields his face. “It protects me from the sun,” he grins. Each morning, he joins the class and learns what everyone else learns, but often leaves early as there’s work to be done — he is a shepherd and must tend to his goats. The little he earns from collecting grass and watching over the herds, he hands to his mother.

When asked what his father does, he smiles with blank eyes. “Mani pith, mani pith ady cryshtal kasheeth (my father uses crystal meth),” he says.

What will he do after the project ends? Usman shrugs and looks over at the girls in the class, many of whom returned to school after years. “I’ll wait another seven years,” he laughs. The chuckles follow, reverberating through the school’s weak walls. But the silence returns the next moment, heavy and unspoken.

Maryam returned to school this March after a gap of five years. She had once completed fifth grade, yet couldn’t spell her own name. “Now I can,” she says, a hint of pride tucked behind her shy smile.

She recalls those early school days with a dry laugh. “The teacher would show up early, stay for an hour, and then vanish. We’d be thrilled, we could go home!” Maryam pauses. “We thought that was happiness. Now we know it was not.”

The current project offered her another chance. But with only 18 months promised, uncertainty looms again. “If this ends,” she says, “I’ll ask the whole class to stage a dharna (protest). But I don’t know where we’d even go. No one listens anyway.”

Against all odds

Only two teachers run this middle-school-level class in Dasht: Mahwish, who travels from Turbat city, and Shabeena, a local from Dasht. Each day, Mahwish makes the bumpy journey to Kont-e-Dar, often passing children walking alone or in clusters along the dusty road.

“Sometimes I give them a lift,” she says. “They come from different bazars, and when they see my car, they start running. They know the teacher is here.”

Their rush, she adds, carries a history. “Maybe it’s because they’ve grown up not expecting teachers to show up. So when one actually does, they run not to miss it.”

At 22, Ganjatoon is married and back in school after a six-year hiatus. She doesn’t speak in abstractions. Her words are blunt. “Ma zaalbol eda barbaady (we women here are suffering),” she says in Balochi.

In her part of Dasht, she says, it feels like there are no men left. “Most are addicted. Some sell drugs openly. If anyone dares to complain, the naib arrests them, but then a phone call comes, and the drug seller walks free.”

She traces the suffering back to the shoulders that carry everything. “We women do it all,” she says. “From farming to embroidery, to fetching water, we have to, because the men are lost to addiction.”

Their struggle doesn’t end with work. Ganjatoon says their homes, made of mud, collapse into crisis every time it rains. “When it pours, water drips from the roof until the house is soaked from top to bottom,” she says. “After the rain, another struggle begins, of drying, rebuilding, just surviving.”

She is aware that the odds are stacked against her. “I won’t get a job because I’m studying,” she says. “That post will go to someone who will never show up to teach.” But still, she shows up every day.

“I will study so that at least I can teach the children in my bazar when this project ends. I want to keep them away from nasha.”

Promises or distant echoes?

Aurelia Ardito, chief of education at Unicef Pakistan, acknowledges both the progress and persistent gaps.

“Kech is among the top-performing districts in Balochistan, second only to Quetta,” she notes, citing Education Management Information System 2022–23 data showing over 86,000 enrolled students. Girls’ enrollment rose by 30 per cent in recent years, and progression rates surpass provincial averages.

“But in Dasht, challenges remain — missing infrastructure, no toilets, no electricity, and serious teacher shortages.”

The district education officer of Kech, Sabir Ali, confirms these struggles. “Most schools are single-teacher institutions,” he says. “If that one teacher is absent, the school simply can’t run.”

He says the education department is developing a 365-day plan for Kech — with reforms in teacher attendance, filling vacancies, and improving quality. Unicef, too, emphasises its commitment to supporting education in Balochistan and beyond.

But for the 49 students in this dust-walled classroom, the promises are distant echoes. They have already spent years watching schools remain locked, waiting on teachers who never came, and watching futures slip quietly out of reach. Whether this school will continue once the project ends — or slip back into silence — is a question that lingers like chalk dust in the dry air of Dasht.

Yet, the students of Dasht show up every day. Because hope, here, is not a policy. It’s the act of walking miles in the heat, of sitting on hard desks, of vowing to teach the next child even when no one is teaching you.

Header image: Students sit outside their classroom in Dasht. — all photos by author