Patriarchy’s toll on health: The invisible struggle of women suffering from heart diseases

Aneesa Bibi*, 67, cooks food at two homes to make a living. She lives with her husband in a rented two-bedroom house located on the first floor in a middle-class neighbourhood in Karachi.

At the entrance is a small kitchen, which leads to a large room with two single beds. The other room is smaller and has a few plastic chairs, a drying stand, a trunk, and a few other things. Bibi’s only child, Raheel, lives on the ground floor of the same house with his wife and two children.

Bibi was diagnosed with a cardiovascular disease (CVD) since the past two years, when she started experiencing severe chest pain. At the time, her son took her to the Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre (JPMC) — the city’s largest public sector hospital — after the doctor at a local clinic, and two private hospitals refused to treat her. Subsequently, one of her heart valves was replaced in a successful surgery at the hospital.

Following her surgery, the doctors instructed her to have two proper meals a day. While Bibi enjoys cooking, she has largely been unable to follow the doctor’s instructions. Financial constraints and responsibilities limit her food intake to only one meal a day. She does, however, try to cook food with less salt and oil due to her health. “I knew beforehand that salty and oily food is unhealthy. Why should I become an enemy of my own health when I have to do everything myself?” she questioned rhetorically.

The price of poverty

Bibi earns Rs14,000 per month which is barely enough to cover household expenses. She leaves for work at 6am and after cooking at the two homes, she comes home late in the evening.

A lack of family support from her son has added to Bibi’s woes as cooking at home has become a tiresome activity on top of a full work day. “Sometimes, I am so tired that I don’t cook food at all and sleep without eating anything. This happens at least thrice a week.”

Bibi and her husband are not able to eat the recommended amount or quality of food every day. For breakfast, they have one sugar-free rusk with a cup of tea. Then they have dinner. At work, Bibi’s employers sometimes ask her to have lunch or cook food for herself but “the pressure of work is so intense that it has robbed me of my appetite”, she lamented.

Over time, inadequate food intake has created multiple issues for Bibi. She feels dizzy, has trouble sleeping at night as well as waking up in the morning. A few months ago, she had a bad fall, breaking two of her teeth. Despite this poverty-induced hunger, Bibi thanks God for whatever food is available to her.

Of late, the one-time meal she shares with her husband has also become increasingly difficult to afford. She usually cooks mixed sabzi (vegetables) since it is easier to cook. Meat remains a luxury. “The doctor has advised me to have meat once a week, however, I rarely cook it once a month.”

At the same time, the responsibility of earning forces Bibi to work despite her age, stamina and will.

Gendered diets

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death globally, claiming an estimated 17.9 million lives each year. CVDs are a group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels and include coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and rheumatic heart disease, among other conditions. The most important behavioural risk factors of heart disease and stroke are unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, smoking and harmful use of alcohol.

CVD is the leading cause of death in Pakistan. In 2019, 32.84 per cent of deaths in the country were attributed to some form of CVD.

A recent study on the motivators and deterrents to diet change in low socio-economic Pakistani patients with CVD found that structural support, particularly for women, is a major issue.

Dr Rubina Barolia — associate professor at the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the Aga Khan University (AKU) and the lead researcher of the study — stated that structural factors often force female CVD patients to compromise on their own health to accommodate male family members. “In our culture, it is common for men to eat first as quality food is often reserved for them, while women have their meals from whatever is left over,” she said.

Another issue the researchers found in low-income households was that since one meal is cooked for the entire family, the female patients could not make separate meals with less oil and salt. Dr Barolia suggested that the food can be adjusted for the whole family to make it healthier, however, the perception of ‘mareezoon wala khana’ (bland food meant for patients) is a big hindrance.

Professor Khawar Abbas Kazmi is the head of Preventive Cardiology at the National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases (NICVD), Karachi and a visiting faculty member at AKU. In his opinion, family members, as well as the patients themselves have a perception of ‘bland food’ — or any food with special instructions/accommodations — being unmanageable or unsustainable in the long run. This mindset bars them from following doctors’ recommendations.

He differentiated between chronic and acute illnesses, emphasising the differences in diets between the two. A “bland or liquid diet” is usually recommended temporarily to patients with acute illnesses. However, CVD is a chronic illness that lasts a lifetime and requires lifestyle changes.

Everyday meal choices for most Pakistanis are usually unhealthy, containing high amounts of fats and high carbohydrates, making it a major cause of heart disease. When a person is diagnosed with a heart condition, families usually opt to make separate meals for the patient. However, this is only followed for a very limited amount of time since it is a laborious task.

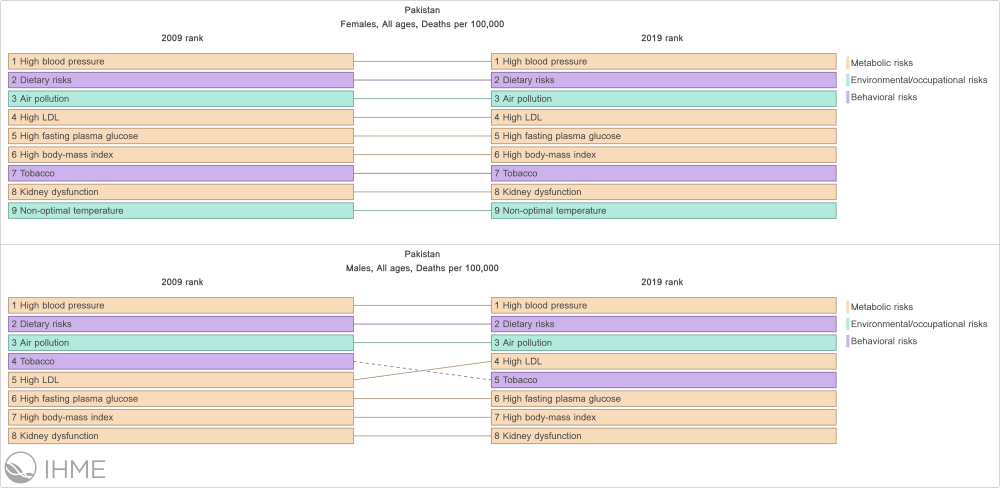

Dietary risks are the second leading cause of death among CVD patients in Pakistan after high blood pressure. CVD patients from lower socio-economic classes usually consider following a healthy diet plan as an unaffordable option as their families are unaware of alternatives.

Sidra Raza is the head of Nutrition and Food Services at the NICVD. She gives her patients two options to resolve the hassle of cooking separate food.

“My first priority is to make patients understand that children develop eating habits at an early age and healthy food choices, with low oil and fat, develop their taste buds accordingly. If they are made to follow a healthy diet since childhood, they most likely won’t face diet-induced heart issues for the rest of their lives. In this case, one healthy meal is cooked for the entire family,” explained Raza.

However, if the first piece of advice doesn’t work, she advises patients to separate their meals before adding oil or salt to it. “It makes a healthy diet for the patient and other family members can eat the usual food.”

The choice between food and medicine

The cost of medicines for CVD patients becomes difficult to manage in a household that is already struggling with basic food expenses. Aneesa Bibi’s medicines for her heart condition and diabetes cost Rs300 a day. She cannot afford to take her medicines daily.

“The basic medicines for a cardiovascular patient cost more than a food basket, which means that one family member has to starve so that the patient can afford to have their medicines on a regular basis,” said Dr Kazmi.

“A lot of (low-income) patients are not sure whether they can afford two-time meals. How can I tell them to have five portions of vegetables and fruits per day?”

For her part, Raza says she performs a detailed assessment of patients’ financial backgrounds before advising them on their food choices. She believes that a healthy and nutritious diet does not mean it has to be expensive. “Even within financial constraints, patients can equally enjoy a well-balanced nutritious diet,” she said.

The dietician shares food combinations that provide a good source of nutrition and are easy to manage. “Beans and mixed lentils are excellent sources of protein. A few drops of lemon juice and a little spinach in mixed lentils make it a protein and iron-rich food that is affordable.”

She also gave the example of seasonal fruits like grapes: “Seasonal fruits are always cheap and they are not required in a huge quantity. Only a handful of grapes (17 to be exact) are enough for one day’s portion size.”

Family support

In her study, Dr Barolia found that children were usually more supportive of their mothers than husbands of their wives with CVD. Children often joined their mothers in having doctor-advised healthier food. However, the mothers also felt guilty that their illness made their children sacrifice their food choices.

Family support for female patients in having healthy food is reflective of society’s gender inequality at large. Dr Kazmi elaborated: “A male patient’s meal becomes a priority and all members of the family are ready to have the same food. However, the same is not true for women with illnesses and special dietary requirements.”

Dr Kazmi held medical personnel responsible for the lack of proper guidance on diet. “Ninety-nine per cent of the time, the patients are given flimsy information about their diet. They are provided with a paper that has information on food choices but are not properly advised on how to go about their diet”.

Furthermore, Dr Barolia also found that food only serves to satisfy hunger for some patients and with the burden of other responsibilities, food and nutrition requirements take a back seat. A research participant stated: “I have to manage the weddings of two of my daughters. How can I think of food choices in this situation?”

Patriarchy and women’s health

Sheema Kermani, a social activist who works for women’s rights, was of the opinion that “the whole issue of women’s health is totally and inevitably related to the issue of women’s status in society”.

“In a highly patriarchal society, women and women’s lives are of little value. Families prioritise their sons’ education over their daughters’. In the context of many rural areas, women’s lives become even more dispensable. A cow is more valuable than a woman. A woman can be easily replaced. A cow costs much more,” said Kirmani.

“Girls are looked upon as a burden — men consider that their family’s honour is vested in girls keeping their virginity intact. Girls also have to be ‘married off’. This becomes a financial, social and moral responsibility.”

“Given this situation, it is no wonder that girls from lower socio-economic households are not fed healthy foods from an early age. They grow up malnourished and are married off while they are still children. Their bodies are underdeveloped, and they are unable to bear healthy children.”

For Kermani, it is no surprise that when a woman has a health problem, the family is not willing to spend money on her.

Header illustration via Shutterstock

*Names have been changed to protect identity.

This write-up was supported by an NHR UK grant to the Aga Khan University.