When women need permission to heal, everyone pays

Maryam, a 28-year-old university lecturer and researcher, lives with endometriosis — a condition that causes debilitating pain. She has made multiple visits to the doctor, knows the procedure required to fix the pain and has the money for it as well. Yet, her days and nights are spent in agony because a private hospital in Lahore, located in her neighbourhood, refuses to treat her.

Why? Because she does not have a man’s consent — her ‘non-existent’ husband’s. Maryam is unmarried, and so, she continues to suffer.

Unfortunately, Maryam’s story is not unique. Across Pakistan, women are routinely told to get a man’s approval before receiving medical care, from reproductive health to diagnostic procedures and even emergency surgeries.

Such practices by healthcare providers don’t just reflect a larger societal thinking, but also disempower women, beginning with households and eventually seeping deeper into the system.

Gatekeeping healthcare

As per the 2024 UN National Development Report, only 12 per cent of women in Pakistan can themselves decide about getting medical treatment in case of a health issue, while 17pc said the decision was taken by the head of the household. Another 28pc said that the matter was decided upon in consultation with other women of the family. On the other hand, a staggering 42pc of women said that everyone in the house, except for the patient in question, got to decide whether a medical treatment was necessary.

This gatekeeping is even more severe in rural areas, where access to basic healthcare is scarce.

But what seemingly looks like social or moral injustice — which it definitely is — is also an economic crisis in disguise. When women are denied bodily autonomy, it is not just a violation of their rights; it is also a denial of economic agency. And when half the population of the country is excluded from making decisions about their own health, the cost is borne by not just women, but by their households and by the country at large. This cost is counted not only in lives lost, but in lost productivity, higher poverty, and stalled national growth.

According to 2025 estimates by the World Health Organisation, 27 mothers and 675 babies under a month old die every single day from preventable complications in Pakistan. That accounts for over 246,000 newborn deaths, nearly 10,000 maternal deaths, and 190,000 stillbirths annually. While maternal mortality has fallen, from 276 deaths per 10,000 live births in 2006 to 155 in 2024, we still rank among the worst in South Asia.

A system built to fail

The denial of healthcare autonomy is not simply a result of outdated thinking, but is in fact enabled by a structural failure in our healthcare system. There is no national law requiring spousal consent for adult women, yet the absence of a clear enforcement framework allows hospitals to impose their own arbitrary rules, thus infantilising women.

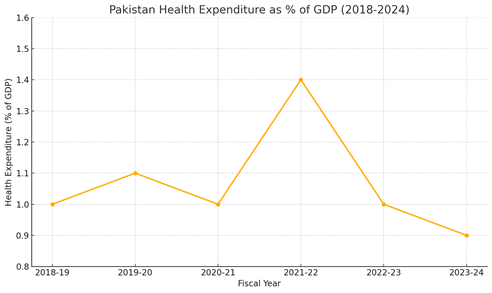

These arbitrary practices thrive within a broader system that is chronically underfunded and blind to gender-specific needs. Pakistan’s public health spending has hovered around 1pc of the gross domestic product (GDP) for the last five years.

This chronic underinvestment has left rural clinics understaffed and urban hospitals overcrowded and costly. Despite high maternal and neonatal mortality rates, there is limited state-level investment in gender-sensitive infrastructure, staff training, or outreach. Reproductive health services — particularly for conditions like endometriosis, PCOS, or miscarriage — are rarely available at the primary healthcare level, despite their prevalence.

Even when legal frameworks exist to support women, access is far from guaranteed. Pakistan’s penal code permits abortion to save a woman’s life, and in early stages for “necessary treatment”, yet stigma, moral policing, and provider bias routinely block care. Without enforcement and sensitivity training, legality remains meaningless for those who need it most.

When facilities are accessible, cultural norms pose another barrier. Women are more likely to seek medical care from female healthcare providers, yet only 46.9pc of registered doctors are women. For patients, a shortage of female doctors deters care-seeking among female patients, particularly where purdah norms prevail.

Unsurprisingly, Pakistan ranks last on the global gender gap index calculated for 146 countries by the World Economic Forum in 2025, and ranked 131st in health and survival, though a slight improvement from its 132nd place in 2024. These are not just rankings — they are reflections of how we’ve built our systems and who we have left out.

The price of denied autonomy

When women are unable to access timely medical care, their participation in the economy suffers. Untreated health issues, particularly reproductive ones, can lead to chronic conditions, lost workdays, and long-term dependency.

According to data by the International Labour Organisation, Pakistan’s female labour force participation is among the lowest in South Asia — rising from 13.95pc in 1990 to just 21.67pc in 2019 — with the lack of reproductive health access being a key, though often overlooked, contributor. Women experiencing undiagnosed or untreated reproductive health issues may be forced to withdraw from both formal and informal employment.

Moreover, women also shoulder disproportionate out-of-pocket medical costs, and delayed treatment often leads to health complications, requiring costlier interventions or prolonged care. Women from underprivileged backgrounds, especially in rural areas, may resort to borrowing, asset sales, or foregoing treatment altogether — further perpetuating cycles of poverty.

On a macro level, a high fertility rate, 3.6 births per woman in 2024, combined with weak maternal health indicators, means Pakistan risks missing its demographic dividend — the economic growth potential that arises when a country has a relatively large working-age population and fewer dependents.

If women, especially young and healthy ones, are unable to access timely healthcare or participate in the labour force due to poor reproductive health outcomes, this window of opportunity closes before Pakistan can reap its full benefits. Countries such as Bangladesh and Indonesia have leveraged investments in women’s health and education to grow their economies. Pakistan, without similar investments, may fail to capitalise on its expanding working-age population.

What needs to change

For women in Pakistan, the right to decide about their own health is far from guaranteed. A national protocol affirming that every adult woman can give informed consent for her own medical care is long overdue — one that leaves no room for interpretation and penalises institutions that flout it.

But legal clarity alone won’t help if care remains out of reach. Reproductive health services for common, and often debilitating conditions like PCOS, miscarriage care, and endometriosis are concentrated in big city hospitals. At the primary healthcare level, these are either missing or handled without privacy, dignity, or trained staff. Raising public health spending above the current 1pc of the GDP and earmarking resources for women’s health could make these services accessible to millions.

At the same time, it is important to understand that the people providing healthcare matter just as much as the facilities. Training healthcare workers to provide respectful and non-judgmental care, especially for young, unmarried, or marginalised women, would restore trust in a system many avoid until it is too late.

Retaining female doctors is equally crucial. While they make up the majority of medical graduates, unsafe workplaces, rigid schedules and and the lack of support drive many out of the profession. Flexible hours, secure facilities, and re-entry programmes would keep them in service and improve access for female patients.

Perhaps, the hardest shift will be in social attitudes. Women should not have to justify a hospital visit, nor seek permission to protect their health. Public awareness campaigns, built on empathy, could help dismantle these norms and affirm that adult women are capable decision-makers.

Denying women the right to make decisions about their own bodies weakens households, burdens the healthcare system, and constrains national growth. This is not just a health crisis or a gender issue — it is a national development failure.

The question is no longer whether women should have autonomy. The question is: how much longer can Pakistan afford the cost of denying it?

Header image: A doctor checks a woman at a makeshift hospital in the Rajanpur district of Punjab. — AFP