Weather wisdom in Sindhi literature: Exploring human-nature interactions in Shah Jo Risalo

Weather stories and folklore are one avenue through which people have historically expressed their interactions with the environment.

They not only capture the ways in which people interact with their environments, but also provide a force of imagination that influences understandings of the self, the universe, and broader perceptions of the human condition.

This article considers stories that have been told about weather in the South Asian context. How have they shaped peoples’ engagement with their environments? How have they aided sensorial experiences of weather? And what is the relevance of such stories in today’s climate-change driven context?

The need for management

Among all the novelties experienced by the British as they colonised South Asia, variable climate stood as a particularly perplexing concern. Beyond the obvious differences, the agency of weather in the South Asian context became a prominent source of anxiety.

From Henry Pottinger’s narrations of the “most sultry weather” of Sindh to early descriptions of South Asian weather as “abhorrent”, “violent” and “hellish”, we gain a sense of the region’s weather — and particularly its heat — as something that needed management.

In part, ideas of “the orient” and “the tropics”, along with emerging scientific categorisations of weather, created a new means of controlling environmental processes that were otherwise deemed chaotic.

As meteorological sciences gained footing in the late 19th century, the ability to predict weather patterns and behaviours substantially improved, making weather less eccentric than previously assumed.

Colonial conversations steered away from puzzlement over the agency of weather and its impacts, towards defining it as something rather platitudinous — weather became reserved as a subject of conversation for when there was nothing left to talk about.

Despite this, weather remains an essential component of physical experiences of the environment, as well as people’s expressions of emotions, in fact and in fiction.

From proverbial references of garmi (heat) to anger and passion, to the metaphorical joy of bahaar (spring) and barsaat (rain), descriptions of weather are not only telling of peoples’ perceptions of their environments, but are crucial insights into the way they may be feeling as a result of interacting with such environments.

In what follows, we use poetry from Shah jo Risalo — a collection by Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai — to explore how weather and the environment are used as forces of imagination, and how they reflect a local ethos of human-nature interactions in Sindh, a province of modern-day Pakistan.

We also underscore the difference between weather and climate in relation to the environment — where the former engages with short-term experiences, the latter spans over a longer duration. We choose to focus on weather and base our understanding on Camille Frazier’s definition of weather as embodied experience and interactions with local environments.

Bhitai’s poetry

Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai was a scholar and a saint, considered by many as the greatest poet of the 17th century. Written in the form of ballads, his poetry narrates the experience of individuals seeking God, emphasising negotiations with the ego.

The Risalo contains 30 thematic chapters, called Surs, of which some illustrate the life stories of widely known and culturally significant heroines — Suhni, Sasui, Lila, Momal, Marui, Nuri and Sorath.

Bhitai’s interest and focus on nature set these tales as rich grounds for exploring human-nature interactions and how they manifest in local realities.

Since the 18th century, various manuscripts of Risalo have emerged with slight differences in translation and analyses.

We focus on two translated versions of the Risalo: the revised and annotated edition by Muhamad Yakoob Agha and translations by Elsa Qazi for secondary analysis.

Our particular focus, Sur Sasui, is among the longest series of Surs, including Sur Abri, Sur Hussaini, Sur Kohyar, Sur Mazuri and Sur Desi, bearing on the story of Sasui and Punhoo. We also refer to Sur Sarang (the monsoon), particularly in its notation of the value of water as a symbol of fertility during times of famine.

What makes Sur Sasui particularly relevant for reflecting localised interactions with weather is the significance it grants to elements such as light and shade, the sun and water, heat and the wind.

Such facets of environmental interaction are not only essential in character development and as a means for exploring the character’s emotional states, but are also crucial in defining the story’s progression, particularly its spatio-temporal placement.

Atmospheric metaphors utilising scorching winds, harsh sunlight, and pouring rain are frequently drawn in order to express the state of the beloved (the primary subject of the poet) and the intensity of their circumstances.

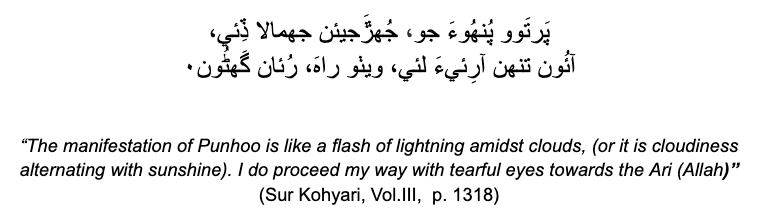

As described in the verse:

Where weather is conventionally understood as scientific, Risalo’s ability to express emotional capacities through various weather elements, and its exploration of how such elements become associated with emotive states are tell-tale signs of locally grounded human-nature interactions, particularly how this dichotomy is understood. Anthropological study of weather tends to establish clear boundaries between what is social and what is ecological, often focusing on humans as subjects that actively interact with a dormant environment, i.e. the object. However, when Bhitai writes:

And further, when he expresses:

Bhitai not only observes the receptiveness of people to nature and vice versa, he builds an image that considers humans in nature, foregoing ideas of defining the two in terms of objectivity and subjectivity, and focusing instead on building exchange and dialogue between the two.

Human-nature synergies in Bhitai’s text thus play an active role in breaking down binaries, suggesting more nuanced approaches to understanding how people position themselves in relation to nature.

In Risalo’s weather stories, we find descriptions of salubrious seasonal rains, intense winds during the summers, and distressing droughts, all of which are expanded on through story arcs of characters such as Sassi and Punhoo, and how their internal states paralleled the environments they inhabited — something that Anderson (2005) described as “weather wisdom”.

Sasui and Punhoo’s characters are also manifested through descriptions of light and shade, darkness and overcast clouds, and most prominently, the sun.

In many verses, shade refers to darkness and light refers to sunshine. Sasui’s emotional state during her struggle to find Punhoo is articulated through the intensity of the weather which leads to the destruction of mountains and burning of trees, rendering the environment uninhabitable.

Among the most prominent themes that emerge in Risalo’s text is that of struggle and hardship, and how those are negotiated using metaphors of heat.

Sasui’s character in particular epitomises struggle, particularly in her quest to find her love Punhoo.

Bhitai elaborates on her agony through descriptions of the prevailing topography of Sindh in the 17th century — the resounding echo of the arid Baloch mountains; the dry, hot, sandy air wafting in the Thar desert; and the suffocating smoke in the city of Bhombore, which he likens to hell.

Sasui’s overarching emotional state throughout her contests are elaborated through her perceptions of the weather that surrounds her, one characterised by the harshness of the sun as it strains her body, blurring distinctions between internal and external perceptions:

While the journey of hardships continues, Sasui musters her strength through her connection with the weather. As her tortuous expedition continues, she fortifies herself with the thought, “you have to keep moving all the time, be it bitter cold or blazing heat”.

In Sur Sasui, the sun is shown as a significant source of the hardship; the sun’s heat exacerbates the beloved’s experiences by making her exceedingly sweaty.

From the heat released from the burning ground, to the feeling of suffocation resulting from the hot winds, for Sasui to cope with the loss of Punhoo, she must prevail through the distress she is subjected to by her environment. Her struggles of love are inseparable from her struggles with the heat.

Sasui lays down in the grove and waits for the perspiration to dry up, just as she tries to remain patient in her search.

On her struggle, Agha writes in his analysis of Shah jo Risalo: “Sasui feels that life without the beloved is gratuitous. Nay, it is a prison worse than hell. She must, therefore, seek reunion with her beloved Punhoo. She is undoubtedly oppressed by the love’s fire, the sun’s heat, the arduous and perilous journey”.

Sasui expresses:

Beyond expressing emotional states through metaphors of heat and weather, Bhitai’s poetry discusses assiduously the economic implications of weather patterns, laying particular emphasis on monsoon rainfalls — a longstanding symbol of hope and prosperity in Sindh.

Aside from experiential understandings, weather is established as a geographical agent, binding spaces across continents under its directional and non-directional movement.

Bhitai especially considers the unequivocal importance of water in his descriptions of economic security:

Rather than making forced attempts to define and patronise weather, these descriptions offer on the ground interactions with the environment that were commonplace in the region. In terms of everyday human experience, weather takes expression through practices, habits, routine, and conversations.

Notably, the only reference to fear in Sur Sarang is made in reference to rain, and it is from the perspective of widowed women.

Widowed women’s helplessness during the rain is compounded by the lack of aid and support from male guardians.

Risalo’s engagement with the gendered implications of monsoon rains shows the use of weather imaginations to address wider cultural norms and concerns, simultaneously complicating the season’s assumed role as a driver of prosperity:

How weather is spoken about has evolved drastically, not only in terms of long-lasting atmospheric changes, but also in the way that people position themselves in their environments, oscillating between conversations about its mystique and mundanity.

It is curious that a strong interest in weather has only now reemerged — under discourses of fear and disasters — in the age of the Anthropocene.

Revitalising stories and narratives of weather that centre around embodied experiences of atmospheric conditions might, we propose, be a starting point for reexamining our fears, and understanding where we stand now, in our weathered environments.

Acknowledgements: This blog is the output of a 3-year project, Cool Infrastructures: Life with Heat in the Off-Grid City, funded by the United Kingdom’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) as part of the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF). The publication can be accessed via the Edinburgh Research Archive. We thank Professor Nausheen H Anwar and Professor Jamie Cross for their suggestions and comments that helped improve the blog.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.