Special Report: The Triumph of Populism 1971-1973

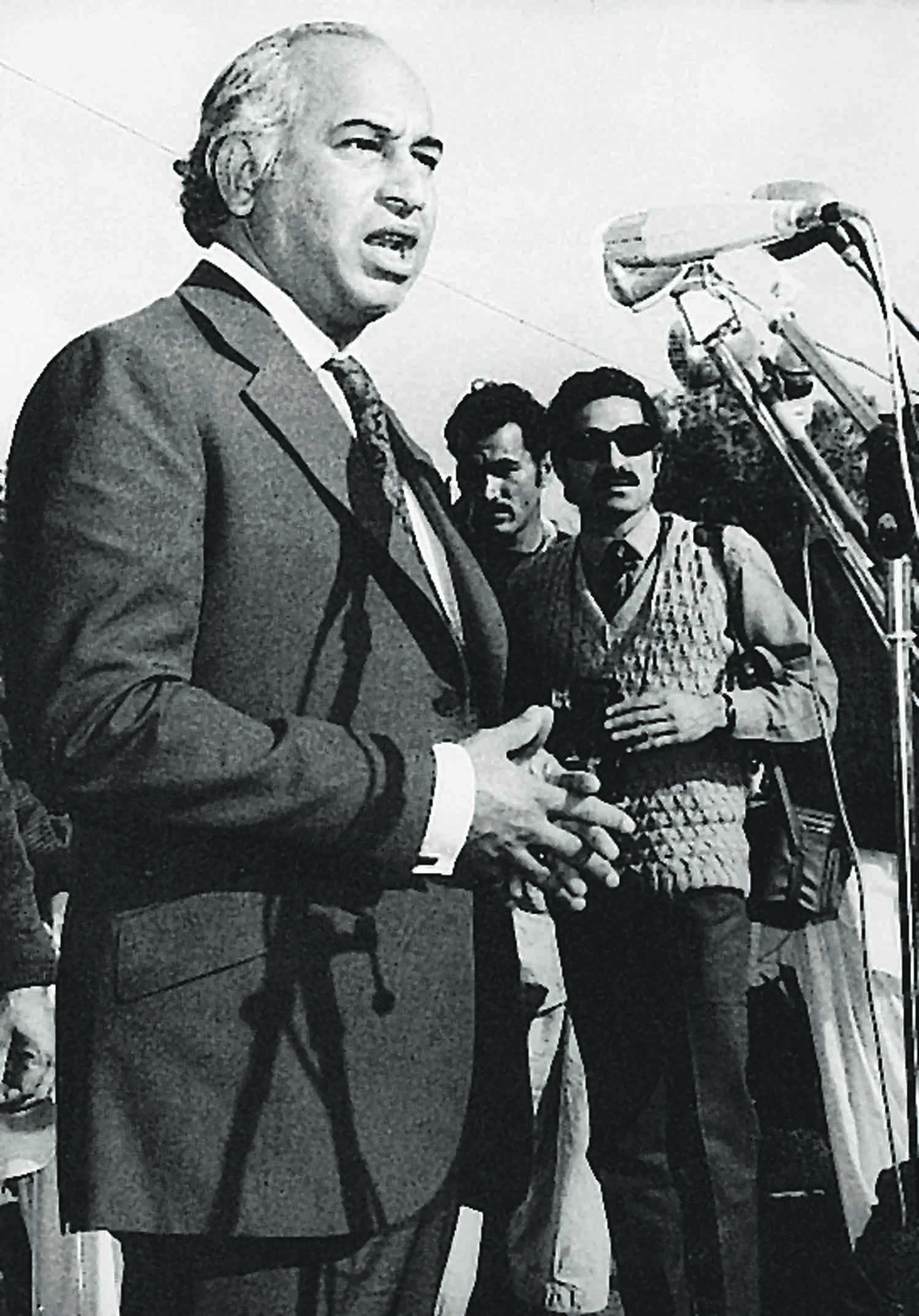

Wearing a Mao cap, Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto is seen in this undated file photo on the top sitting at a dhaba, a roadside eatery, giving seemingly complete access to the common man. It was forays like this that earned him the title of the Quaid-i-Awam – the leader of the people which, in many ways, he actually was.

The promise of democracy

By S. Akbar Zaidi

WITH the surrender of Pakistani troops on December 16, 1971, in Dhaka, Bangladesh came into being, and with that, the end of the Pakistan that Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah had originally created. It also resulted in the end of 13 years of military rule in what remained of the country. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was in New York at the time, flew in to Rawalpindi on December 20, and, with the assistance of a group of the military’s general officers who had been dismayed by Gen Yahya Khan and his core group over the defeat, forcing Yahya out, became the president of Pakistan as well as its only civilian Chief Martial Law Administrator.

Within a matter of days, Bhutto began to put into effect his mandate of the people, based on his electoral manifesto which had won him a majority in the elections in West Pakistan a year earlier. While economic and social reform was a key plank of the Bhutto promise, what needed pressing attention, among numerous things, was the return of the 93,000, mostly military, prisoners of war (POWs) in India.

In 1971, Pakistan had lost not just East Pakistan, but half its navy, one-third of its army, and a quarter of its air force. India occupied 5,000 square miles of West Pakistani territory. The military stood humiliated after the surrender, and this was the first of only two opportunities (the other was in 2008) when elected leaders could have established long-lasting democratic rule in Pakistan.

Bhutto even initiated a judicial commission, under chief justice Hamoodur Rahman, “to prepare a full and complete account of the circumstances surrounding the atrocities and 1971 war”, including the “circumstances in which the Commander of the Eastern Military Command surrendered the Eastern contingent forces under his command who laid down their arms”.

Bhutto outdid himself when he met Indira Gandhi at Simla in July 1972 and got the better of her through his persuasive negotiating skills, and secured the release of Pakistani POWs (who came home in 1974), with India returning Pakistan’s territory, and both countries accepting the ceasefire line in Kashmir as the Line of Control. Bhutto returned a hero, yet again, to Pakistan, not just for the people, but also for sections of the military.

On a parallel track, Bhutto’s leftist economic team was implementing promises that had been made during the election campaign of 1970. With roti, kapra aur makaan the key slogans of Bhutto’s electoral commitment of his notion of Islamic Socialism and social justice, the manifesto of his Pakistan People’s Party had promised the nationalisation of all basic industries and financial institutions.

It had stated that “those means of production that are the generators of industrial advance or on which depend other industries must not be allowed to be vested in private hands; secondly, that all enterprises that constitute the infrastructure of the national economy must be in public ownership; thirdly, that institutions dealing with the medium of exchange, that is banking and insurance, must be nationalised”.

ECONOMIC AGENDA

The economic policies of the Bhutto government rested on the premise that the control of the leading enterprises was to be in the hands of the state. It ought to be pointed out that while this policy of nationalisation has been much maligned by critics of Bhutto, his policies were a reflection of the times and of the age in which they were implemented.

Since Bhutto’s rise to electoral success was based on his populist critique of Ayub Khan’s economic policies of functional inequality resulting in the infamous ‘22 families’, issues of redistribution, nationalisation and social-sector development were fundamental to his economic programme. Literally within days of taking over power, in January 1972, Bhutto had nationalised 30 major firms in 10 key industries in the large-scale manufacturing sector, essentially in the capital and intermediate goods industry.

In March 1972, his government had nationalised insurance companies, and banks were to follow in 1974, as were other industrial concerns in 1976. In addition to nationalisation, extensive labour reforms were also initiated by the Bhutto government, giving labour far greater rights than they had had in the past.

With the need to break the industrial-financial nexus a pillar of Bhutto’s populist social agenda, in a country which at that time was predominantly rural and agricultural, the ownership of land determined economic, social and political power. Bhutto had promised to break the hold of the feudals (notwithstanding the fact that he himself owned much land) and undertook extensive land reforms in March 1972.

In a speech, he said his land reforms would “effectively break up the iniquitous concentrations of landed wealth, reduce income disparities, increase production, reduce unemployment, streamline the administration of land revenue and agricultural taxation, and truly lay down the foundations of a relationship of honour and mutual benefit between the landowner and tenant”.

The PPP manifesto laid the premise for this action by stating that “the breakup of the large estates to destroy the feudal landowners is a national necessity that will have to be carried through by practical measures”. The government had decided that the land resumed from landowners would not receive any compensation unlike the Ayub Khan reforms of 1959, and this land was to be distributed free to landless tenants. The ceilings for owning land were also cut from 500 acres of irrigated land to 150 acres in 1972.

Although a lot of propaganda was churned out about the success of the 1972 reforms, the resumed land was far less than was the case in 1959, and only one per cent of the landless tenants and small owners benefited from these measures. Nevertheless, like labour reforms, tenancy reforms for agricultural workers and for landless labour did give those cultivating land far greater usufruct and legal rights to the land than they previously had.

Along with these structural interventions in the economy which changed ownership patterns and property rights, an ambitious social-sector programme, consisting, among other things, of the nationalisation of schools and initiating a people’s health scheme providing free healthcare to all, was also initiated.

However, while economic and social reform was a key plank of the Bhutto promise and his energies were also consumed by the process of getting the POWs released, giving Pakistan its first democratic constitution was also high on his agenda.

Although 125 of the 135 members of the National Assembly voted for Pakistan’s Constitution on April 10, 1973, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto is given, and deservedly so, credit for making a large, discordant group of nationalists and Islamists to agree to the draft.

To get leaders like Wali Khan, who was the parliamentary leader of the opposition, Mir Ghaus Baksh Bizenjo, the sardars of Balochistan, Mufti Mahmud, and Mian Tufail, who had replaced Maulana Maudoodi as the Jamaat-e-Islami Amir, to build a consensus on a document that would determine Pakistan’s democratic trajectory was a major feat.

The Constitution came into effect on August 14, 1973, setting out a parliamentary form of government, with Bhutto as Pakistan’s first democratically elected prime minister. Since Bhutto ruled the Punjab and Sindh, he had made concessions to the nationalists in order to make them agree to his terms. Ayesha Jalal quotes Bhutto as saying that while Wali Khan “vehemently opposed” the Constitution, he skilfully manoeuvred the Khan and “smashed him into becoming a Pakistani”.

A key clause in the 1973 Constitution required members of the armed forces to take an oath promising not to take part in political activities and making it illegal for the military to intervene in politics. Clearly, the military did not read or care for the Constitution either in 1977 or in 1999.

NATIONALISTS AND THE MILITARY

While the PPP had its governments in the Punjab and Sindh, the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) and Balochistan were ruled by coalition governments formed by the National Awami Party (NAP) and the Jamiat-e-Ulema Islam (JUI) which gave a voice to Baloch and Pashtun nationalisms of the 1970s variety.

In February 1973, weapons were found in the Iraqi embassy in Islamabad that were supposedly meant for armed insurrection by the nationalists in Balochistan. On February 14, Sardar Attaullah Khan Mengal’s government in Balochistan was dismissed, and the next day, the NAP-JUI government in the NWFP resigned, while Bhutto’s governor in Balochistan, Sardar Akbar Khan Bugti, resigned in October 1973 as a political crisis emerged and grew stronger by the day.

Many of the sardars and their tribesmen had started a militant movement for a Greater Balochistan, joined in by many Cambridge-educated scions of elite households, largely from the Punjab. Bhutto called in the military, with General Tikka Khan, dubbed by many as the ‘butcher of East Pakistan’, to curb the armed uprising and for Tikka Khan to add another accolade to his titles, that of the ‘butcher of Balochistan’.

So soon after having lost political and public support, once again, a constitutional crisis slowly brought in the military into a position of increasing prestige and prominence. The lessons of just a few years ago, of giving nationalists their rights and accepting electoral outcomes, were once again being brushed aside by the same democratically-elected leader, and, indeed, by the military.

EARLY SIGNS OF AUTHORITARIANISM

As his rule progressed, we see clear signs of hubris and authoritarianism emerging in the political practices of Bhutto, but there were early signs which may have suggested what was to come, with Shuja Nawaz and many other authors seeing the rise of an eventual “civilian dictatorship”. One example of this was the decision to set up the Federal Security Force (FSF), a paramilitary organisation, so as not to rely on the military, as early as September 1972. The FSF, whose head later became a state witness in the infamous Bhutto trial, was once seen as ‘Bhutto’s private military arm’.

Furthermore, it is ironic that while Bhutto was a social democrat, giving numerous rights and powers to the downtrodden, to the labourers and to the peasants and landless workers, he also used the power of the state to undermine the force of the street, particularly in Karachi. In the summer of 1972, organised trade unions in Karachi took to the streets and initiated industrial action in the form of strikes, but were met by a brutal police force resulting in the death of a number of workers. Organised labour, which had supported Bhutto’s rise, was dealt a harsh blow about the reality of incumbent politics.

Like Jinnah, the Quaid-e-Azam, before him, 24 years later, Bhutto, the Quaid-e-Awam, was building a new country. Both had dismissed provincial governments and showed signs of an incipient authoritarianism and desire for centralisation and control. We do not know what Jinnah would have done had he lived, but Bhutto’s democratic and socialist credentials were soon to come undone.

Arrogance and clear signs of intolerance of dissent were emerging in the Pakistan of 1972-73. Many of the promises made in the late 1960s and the early 1970s by Bhutto were to be played out between 1974 and 1977, setting a stage for Bhutto’s regional and global aspirations and ambitions.

However, perhaps it was the same ambition and confidence that had led him to an electoral victory in 1970 which was to become a cause for his eventual downfall in 1977, and then death in 1979. He had also made far too many enemies along the way, and many of them were just waiting for their opportunity to settle scores. Between 1974 and 1977, Bhutto was to give them many such opportunities.

The writer is a political economist based in Karachi. He has a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge, and teaches at Columbia University in New York and at the IBA in Karachi.

This story is the sixth part of a series of 16 special reports under the banner of '70 years of Pakistan and Dawn.' Visit the archive to read the last 5 reports.

*HBL has been an indelible part of the nation’s fabric since independence, enabling the dreams of millions of Pakistanis. At HBL, we salute the dreamers and dedicate the nation’s 70th anniversary to you. Jahan Khwab, Wahan HBL.*

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

A FRESH START

DAWN December 21, 1971 (Editorial)

The change to civilian rule

IN deciding to lay down his office and transfer authority to the representatives of the people, President Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan has shown understanding of the country’s present mood and of the urgent need for political change. It was inevitable that the tragic events culminating in the political-cum-military debacle in East Pakistan should have created a grave crisis of confidence. The events of the last few days have shaken the country and given rise to an earnest demand for a wide-ranging review of the current posture of affairs and for a new supreme effort to enable the nation to tide over what probably is one of the worst crises the Muslims have faced since their arrival in the sub-continent.

The country is where it finds itself today after two successive military regimes have held unchallenged sway over it for over 13 years. This long period has been characterised by the virtual suspension of the political process, the usurpation of the policy-making functions by bureaucrats, the absence of accountability at almost all levels of government, and the loss or impairment of civil liberties and the freedom of expression. Our experience has amply shown that military government is neither more efficient nor stronger than civilian representative government. We shall be failing in our duty if we do not point out here that the grave situation the country faces today is in no small measure due to the persistent denial of freedom of expression.

***

BHUTTO ADDRESSES THE NATION

DAWN December 22, 1971 (Editorial)

Accountability and freedom

MR. ZULFIKAR Ali Bhutto’s first broadcast to the nation as Pakistan’s President has given the people some idea of the approach he intends to bring to problems of government and politics. What he has said about restoring true democracy at the earliest possible moment, ending the state of political suffocation which has lasted so long and making the Government accountable to the people is heartening. Mr Bhutto has also announced certain decisions which are in conformity with the spirit that informs his address to the nation. Our reference here is to the lifting of the ban on the National Awami Party, the annulment of the so-called by-elections held in East Pakistan and the decision to release all political prisoners except those charged with treason. These decisions are expressive of a desire to move towards the liberalisation of a political order which has for long been largely based on the containment of democratic urges and the negation of popular rights.

***

NATIONALISATION GETS UNDERWAY

DAWN January 3, 1972 (News Report)

10 basic industries put under people’s control

PRESIDENT Zulfikar Ali Bhutto announced last night [January 2] that he had placed control of 10 categories of basic industries in the hands of the state “for the benefit of the people of Pakistan”. He listed the 10 categories as follows: iron and steel industries; basic metal industries; heavy engineering; heavy electrical industries; assembly and manufacture of motor vehicles; tractor plants — assembly and manufacture; heavy and basic chemicals; petrochemical industries; cement industry; public utilities — electricity, generation, transmission and distribution; gas and oil refineries.

President Bhutto said that the industries taken over “bear upon the life of every citizen and form the base without which no industrial development in the real sense can take place.” The control of these industries now rests with the State of Pakistan for the benefit of the people of Pakistan”, he said, adding that the “people are now in charge of their own industrial development”.

The Central Finance Minister, Dr Mubashir Hasan, last night announced the takeover of 20 industrial units falling within the purview of the 10 categories.

***

INDUSTRIAL STRIKE CRIPPLES KARACHI

DAWN January 6, 1972 (News Report)

Rash of ‘gherao’

THE country’s biggest industrial complex – Sind Industrial Trading Estate (SITE) – came almost to a standstill yesterday [January 5] when over 20,000 workers belonging to about two dozen industries struck work and ‘gheraoed’ their respective top bosses for the fulfilment of their “just and genuine” demands.

Appeals by leaders of the ruling People’s Party did not wholly succeed in refraining the workers from the ‘gherao’ tactics which they thought was the only way to get their demands accepted. Their main demands were: reinstatement of retrenched workers, increase in salary, full medical facilities, and grant of two-and-a-half per cent share in profit. According to a conservative estimate, about 45,000 workers have been retrenched in Karachi alone under proclamation of Martial Law by Yahya Khan’s regime.

The workers of various mills in the SITE staged demonstrations before their respective mills the whole day, calling upon the owners and managements to come to some settlement. There were those who reacted favourably and the ‘gherao’ came to an end.

***

DESTINATION NOT KNOWN

DAWN January 9, 1972 (News Report)

Mujib flies to freedom

SHIEKH Mujibur Rahman flew out of here [Rawalpindi] at 3am today [January 8] by a chartered PIA plane. The destination had been kept secret in deference to his wishes. Freed from detention of nine months and 13 days, Sheikh Mujib was personally seen off by President Bhutto, along with the Punjab Governor, Mr Ghulam Mustafa Khar. Before the Sheikh’s departure, President Bhutto had nearly four hours of talks with him. President Bhutto said that he met Sheikh Mujibur Rehman twice yesterday prior to his departure. The first meeting was from 7pm to 9.45pm, and the second from 1am.

The President said this when he was surrounded by pressmen as he arrived to receive the Shah of Iran. The questions asked on the occasion all related to the release and departure of Sheikh Mujib. He did not say anything about the outcome of his talks with Sheikh Mujib.

***

NUCLEAR CAPABILITY VITAL: BHUTTO

DAWN January 22, 1972 (Editorial)

Science for progress

ADDRESSING the science conference in Multan, President Bhutto announced the creation of a separate Ministry of Science, Technology and Production. Mr. Bhutto has beckoned scientists to their vital role in redeeming national honour and contributing to the country’s progress. The setting up of a Scientific Pool to attract scientific talent and check the ‘brain drain’, and the creation of 10 Presidential awards for technological innovations are steps in the right direction. The Multan conference was primarily concerned with the question of developing nuclear science which the President described as vital for progress and defence. He recalled that while India had launched her programme of nuclear development in the early 1950s, it was Pakistan’s choice to initiate moves in the UN to keep Pakistan and other non-nuclear member nations permanently non-nuclear, “which in other words means remaining backward”.

Atomic research has brought about a fundamental revolution by which large sections of our civilisation will presumably be remodelled completely. Apart from engaging qualified and trained scientists in various Government undertakings, there is also need for building up a system of scientific thinking and evaluation. This can be immensely helpful to the Government in economic planning and in the appraisal of various projects.

***

ACTION AGAINST DAWN CONTINUES

DAWN February 6, 1972 (News Report)

Altaf Gauhar arrested

MR Altaf Gauhar, Editor-in-Chief of Dawn group of Newspapers, was arrested under Martial Law Regulation. No 78 from his residence in the small hours of yesterday [February 5] morning. Official sources said in Rawalpindi that the action against Mr Altaf Gauhar had been taken on grounds relating to his removal from government service during the 1969 round of screening and his activities thereafter.

***

NO GROUND GIVEN: BHUTTO

DAWN July 4, 1972 (Editorial)

The Simla Agreement

THE Agreement signed at Simla by President Bhutto and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi will meet with the approval of all men of goodwill as a sane beginning towards ending the era of futile – and sometimes foolish – wars between Pakistan and India. These conflicts have, since Independence, compelled both peoples to devote a disproportionate part of their energies and resources to the means of destruction, and have, thus, condemned themselves to continuing poverty and all the human suffering that it connotes. The most significant part of the Simla accord, therefore, is that it seeks to evolve a new pattern of relationship for the two States, based on mutual trust, acceptance of each other’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and a common desire to live in peace. With far-sighted wisdom, the acknowledged leaders of Pakistan and India have been able to exorcise the demons of past years and suspicions and have agreed that, henceforth, their Governments will refrains from the use or threat of force, and will seek to settle all their differences through bilateral negotiations or other peaceful means mutually agreed upon, in accordance with the principles of the U.N. Charter; and, with political good sense, they have realized that only through a correct response to their peoples’ urge for peace can their Governments fulfil the common man’s expectations for a better life. Apart from such joint declarations of future good intentions, priority has rightly been given to removing the effects of the last Indo-Pakistan war. The Agreement stipulates that, within 30 days of its ratification, the territories occupied by either country along the recognised international border will be vacated. This means that the large areas in the Punjab and Sind now under Indian occupation will be free in the near future, allowing many lakhs of our uprooted people to return to their homes. This partial agreement on the withdrawal of troops to the positions they held on December 3, 1971, leaves the status quo in Jammu and Kashmir unchanged. Another major issue that has been left for future determination is that of the repatriation of the Pakistani prisoners of war now held in India. Although this has not been stated in the Agreement, India has expressed its willingness to release all prisoners captured on the Western front; but it maintains its position that the disposal of the prisoners captured in the war in East Pakistan can be decided only with the concurrence of the Bangladesh Government.

***

RIOTS HIT KARACHI, HYDERABAD

DAWN July 9, 1972 (Editorial)

The language issue

THE tragic turn the language controversy has taken in Karachi and in other cities hardly redounds to the credit of the elected representatives of the Province. The reported burning of the Sindhi Department of the Karachi University should make every sane person in the Province, whether he speaks Urdu or Sindhi, hang his head in shame. In the last analysis, it is the people who will suffer for the shortcomings of those they had elected. The clashes between the demonstrators and the Police were bad enough on Friday [July 7], but on Saturday about 12 persons are said to have been killed, and the Army has been called in. There can be no rational explanation for the unjustified haste with which both sides acted or, probably, reacted. The protagonists of Urdu did not serve their cause well by their precipitate protest strike without fully ensuring that they had enough resources to keep the demonstration peaceful. The Ministerial party did not aquit itself of its duties any better. No harm could have been done to anybody if the Government had resisted the temptation to bulldoze the Bill through the House.

The most amazing thing is that in spite of the long and repetitive statements from both sides, it is still not easy for the common man to know how exactly the law will affect him. Confusion is worse confounded by the Opposition claiming that a certain provision of the new law “will strike a death blow to the non-Sindhis and will practically eliminate them from Government departments” and the Chief Minister’s assertion that there would be no discrimination between old and new Sindhis in the services. The Government spokesmen have also said that “Urdu would be allowed to flourish and grow at all levels along with Sindhi” and that “Article 267 of the Interim Constitution has fully protected the superior position of Urdu”. They have, however, neglected to state clearly the practical import and the operational effect of these assertions under the new law.

***

GOVT MOVES AGAINST MEDIA

DAWN July 24, 1972 (Editorial)

Drastic action

ONE week ago, the Government of Pakistan decided to invoke the draconian Defence of Pakistan Rules to cancel the declaration of a local daily, The Sun, forfeit its printing press and confiscate all copies of its last issue, dated July 17, in which it is said to have contravened the Censorship Order banning the publication of news and comments related to the language issue without prior approval of the censors appointed for this purpose. This drastic action has been deplored by all those who believed that freedom of the Press is an essential part of the democratic process, and that democracy cannot prosper unless the Press is guaranteed its basic rights and all suspicion of victimisation is eliminated by restricting Government action against newspapers to what is permissible under the ordinary law – and is carried out in accordance with the due process of the law.

With regard to the specific offence with which the newspaper is charged, the conclusion that this was deliberately done in order to fan parochial passions has to be proved before it can be accepted in fact. Copies of what was said to be a draft of that proposed Ordinance were being circulated among newsmen at the time, and it is difficult to believe that any newspaper would consider it appropriate to publish such an important document, in the context of prevailing circumstances, except in the belief that it was genuine. Further, it has now been shown that the version published by The Sun is not substantially different from the final text of the Ordinance amending or clarifying the Language Bill.

In any case the technical offence of a breach of the Censorship Order does not call for such harsh punishment. The seven days’ closure that the newspaper has already suffered is punishment heavy enough by any standards.

***

KARACHI NOT TO BE SEPARATED FROM SINDH

DAWN July 30, 1972 (News Report)

Bhutto decries Sindhu Desh

PRESIDENT Zulfikar Ali Bhutto today [July 29] categorically declared that Karachi was an integral part of Sind and none could separate it from the province. He also castigated those who raised the stunt of Sindhu Desh and added that it was an empty dream which would never materialise.

The President was addressing a citizens’ meeting at Tando Mohammad Khan. He said the turbulent state of affairs in the so-called Bangladesh should serve as an eye-opener to those who were dreaming of Sindhu Desh. He cautioned the people against disruptionists who, he said, were trying to create fresh trouble. He said the people’s Government was fully alive to the situation and was having a strict watch on such moves which, if developed into chaotic conditions, would be dealt with in the larger interest of the country.

He said that at Sanghar he was asked who would inquire for the welfare of Muhajirs in Sind in the manner it was done for Punjabis and Pathans for whom deputations were coming from the North. He replied to such queries that he (President) had himself come to look after the interest and well-being of the Muhajirs and would keep on doing so as and when necessary.

***

ASGHAR KHAN’S HOUSE UNDER ATTACK

DAWN August 3, 1972 (Editorial)

A vicious crime

THE mysterious fire which has destroyed the Abbottabad residence of Air Marshal Asghar Khan was, according to an agency report, started with some “explosive material”; and it was apparently employed with such deadly efficiency that the local fire brigade, assisted by volunteer helpers, could not control the flames, and the building was completely destroyed. Since the Tehrik Chief has for some time been the special target of the ruling party’s ire, for his blunt criticism of the regime and this is not the first strange happening affecting him, it is difficult to believe that this vicious and dastardly crime was merely the act of some mad arsonist. It will be recalled that a few weeks ago, the Sukkur farm owned by Asghar Khan and his wife was forcibly occupied, and it is alleged that the takeover was master-minded by local PPP workers; and, what is more disturbing, the district administration seems to have taken no effective action on the complaint filed by the Air Marshal’s representatives, compelling him to seek redress from the law courts. Going farther back, during Asghar Khan’s political tour in February, his meetings in a number of towns were deliberately disrupted, and, in Lahore, a fracas was provoked in a local hotel presumably by a group of PPP leaders.

It is the obvious duty of the local administration to investigate the latest case involving the Tehrik Chief so that if it is at all possible those responsible for the horrible crime should be brought to book and suitably punished. The seizure of his farm must also be investigated and dealt with in accordance with the law. However, in the circumstances, it is equally essential that the top leadership of the PPP should take effective steps to bring under control the party’s lunatic fringe who seem to imagine that, since the PPP has attained political power, they have somehow acquired the right to determine the extent and type of political activity that is permissible in the country. This intolerance of dissent, particularly when it is sought to be supported by violence, is a dangerous trend which must be suppressed before in leads to chaos in our political life.

***

CONSPIRACY AGAINST CIVILIAN RULE

DAWN August 12, 1972 (Editorial)

Army officers’ plot

THE startling disclosure made by the Special Assistant to the President that six senior Army officers had been found guilty by a military Court of inquiry of being involved in a “conspiracy to plunge the country into civil war” will be viewed with grave concern by every citizen. And since the vast majority of our people believe that the involvement of the Armed Forces in political affairs has already done the country a great deal of harm, they will expect that every necessary step should be taken to ensure that the Defence Forces are concerned only with their primary task of defending the country’s borders and are not, under any circumstances, allowed in any manner to influence political decisions. The timing of the plot by the officer named as its authors, including one Major General and two Brigadiers, is obviously not without significance; and it will generate speculation on whether it was aimed at the dying military dictatorship or sought to forestall the civilian rule. We would suggest, therefore, that the Government should re-consider its decisions and reveal the precise nature of the conspiracy. A certain measure of mystery surrounds the events of the crucial days of December when a demented military dictator led the country from one crisis into another and, according to widespread reports, tried till the very end to maintain his stranglehold over West Pakistan; and when he saw that this was not possible, it is said that he sought to appoint a trusted successor so that the power could remain with the junta that had already led the country to disaster. It seems necessary that a truthful account of the Yahya regime’s last days should be made known, so that rumour-mongers are not able to impose their versions on the people.

***

MEDIA-GOVT TIES HIT NEW LOW

DAWN November 23, 1972 (Editorial)

Attack on DAWN

AN official spokesman of the Central Government has, with as little regard for truth as for the norms of civilized discourse, made a vicious attack on this newspaper and its Editor. It would demean these columns to take serious notice of the foul-mouthed invective used on the personal plane; this can best be ignored except to point out that it is both false and malicious. However, the vague, unspecified allegations about the policy of this newspaper and its associates require refutation.

Ostensibly, the main purpose of this exercise in bad manners was to state that DAWN does not reflect official thinking on “some aspects of external relations”. No such claim has ever been made for this newspaper or its Editor.

With regard to the series of articles on the reality of Bangladesh, this position was made abundantly clear in a foot-note published prominently along with the first article. It was said that “the aim of our visit” to Bangladesh (and India) “was to seek interviews with their leaders”, and “to meet other people and understand their point of view”. And further, “when we gave an opinion there was no doubt in any mind that these were our views and that we did not speak on behalf of anyone”. However, if, despite this clearly-worded statement, some people have gathered such an impression, we agree whole-heartedly that it is not the truth; and if official thinking is reflected by this particular official spokesman, God forbid that it should be anything but “the opposite of the truth”.

The present policy of this newspaper is perfectly clear; it gives support to those Government policies which, in our opinion, merit support and serve the national interest, and criticises those actions or policies which, in our opinion, are misconceived or can do harm to the country. It is our intention to maintain this approach, no matter what the provocation. But if we have – without meaning to do so – deviated from this correct standard on any issue, for example, by not focussing sufficient attention on the follies or foibles of Authority, we owe an apology – to our readers.

Whatever the motives of the base attack made by Government’s spokesman, it is completely misguided and wholly baseless. We will not even attempt to explore the convoluted thinking behind the statement made by the official spokesman that criticism of the Generals’ Junta “might have had some justification after the surrender of Dacca” – or his clear implication that in respect of the actions which are known to have led up to this tragic denouement, we should bury our heads in the sand. We also wish to make it clear that it is absolutely untrue that this newspaper or its Editor has “assailed the honour and integrity of the Armed Forces of Pakistan”. Criticism of the military-bureaucratic combine which led the country to disaster cannot, and does not, cast any reflection on this vital institution. We whole-heartedly agree that the Government has a duty to safeguard the integrity of the country and the honour of the Armed Forces; and we firmly believe that this can best be done by ensuring that the democratic rights of the people of Pakistan are fully safeguarded, and that the Armed Forces are permitted to perform their primary role of being fully prepared to defend the country’s borders against possible foreign aggression and any other duties assigned to them by the democratically elected civilian authority.

We believe, and have clearly stated in these columns, that the best guarantee of the country’s unity and integrity lies in establishing a democratic system based on the assurance of a reasonable measure of provincial autonomy, as required by the circumstances of this country. It is relevant to point out here that the tribe of morons who parade as the sole defenders of the Pakistan ideology, and imagine that this can be preserved best by suppression of divergent opinion, have, since Partition, done the country a great deal of damage.

With regard to the threat of action against this newspaper or those associated with it, for the present Editor the experience of having unproved and unprovable charges levelled at the newspaper by Government functionaries, for easily discernible ulterior motives, is not a new one. It has all happened before; and in the name of some surrealistic concept of Press freedom, the Press has been smothered and emasculated. If certain elements in the present regime wish to march in Ayub Khan’s footsteps along this dangerous path, those who wield the scepter certainly have the physical power to do so, but they should not try to insult the intelligence of the people by seeking to create moral justification for a policy or action that may help some petty-minded official to overcome his frustrations – but can only do the country’s wider interests a great deal of harm.

***

MARRIS, BUGTIS IN TUSSLE WITH GOVT

DAWN December 5, 1972 (Editorial)

Trouble in Baluchistan

THAT Baluchistan’s transition to democracy should have been beset with difficulties is understandable. It is particularly unfortunate that some persons have done and said things which could only be intended to promote confusion and chaos. All previous attempts to upset the Ministry having failed, two moves have been made, more or less simultaneously, to stimulate conflict and create a law and order problem. In the first place, a number of villages belonging to non-Baluch settlers in the Pat Feeder area have been raided and their cattle and possessions taken away by a band of Marri and other tribesmen and one village has been forcibly occupied. The second tentacle revealed itself at Quetta. A group of Bugti tribesmen sought, by a show of strength, to force the Finance Minister to resign, because, according to them, his elder brother, the tribal Sardar, had refused to return to Pakistan unless his younger brother dissociated himself from the NAP Government. The Bugti tribesmen spearheaded what was perhaps intended to be a putsch of some sort.

It need hardly be said that the Provincial Government’s efforts to deal with the intrigues of megalomaniac Sardars or dissatisfied contractors, and to curb the impatient avarice of hungry tribesmen encouraged by elements bent on mischief, must get the Central Government’s fullest support.

***

LACK OF REALISM MARKS QUAID’S BIRTH ANNIVERSARY

DAWN December 25, 1972 (Editorial)

Mountains don’t cry

YEAR after year, as an impersonal routine, an assessment is attempted of the prevailing state of affairs on the Quaid-i-Azam’s birth anniversary. The exercise is intended to reassure ourselves with platitudes and homilies. The real questions are seldom raised. There are two dominant elements in the present situation; the first is fear and the second our spectatorial attitude. Everyone is so careful, so wary, watching and observing as if holding a quiet trial of others. The preoccupation is to ensure that no one should act or do anything. The more considerate advise, with varying degrees of urgency, to ‘lie low’, and add in hushed whispers, ‘or you will be laid low’. The assumption is that while we are a ‘great people’, as individuals we are inconsistent, whimsical, cowardly and of no consequence. A heavy cloud of silence and suspicion is overhanging. The second element is more difficult to describe. Our whole attitude has become Spectatorial. Since the ‘spectator oft times sees more than the gamester’, it is unnecessary to involve ourselves in the game.

All this will, of course, be rejected as cynicism or something more sinister and the language of rejection will be self-righteous and charged with emotion. We have developed a highly ornate and flamboyant expression to cover our fear and non-commitment. With the increasing lack of purpose, words are now used as an end in themselves, not to communicate but to create an impact with sound alone. It is never enough to say that “the offenders will be dealt with according to law”. It must be made known that ‘the offenders will be wiped out’. Since ideas are of little relevance, we tend to overwork the words. Having knocked all sense out of “ideology”, “integrity”, and “solidarity” we are now busy draining whatever meaning is left in “reality”, “principles”, and “the people”. It is supposed that if slogans are repeated often enough they will become ‘concepts’ and opinions voiced loudly and forcefully will be accepted as ’ideas’.

All kinds of skillful formulations are used to describe the situation resulting from the fall of Dacca in December 1971. It is claimed with considerable ingenuity that we have become ‘stronger than before’. Which is sufficient justification to double the size of the administration even though the country has been halved. That, in the meantime, all moral pride and sense of honour may be seriously impaired does not seem to be relevant.

It is in this perspective that Government-Opposition relations during the last 25 years should be viewed. The Opposition has always agitated, the Government has always advocated reasonableness. It has always been the people against the Government. The people have demanded, the Government has resisted; the people have agitated, the Government has suppressed. The Opposition promises, the Government fails. The people hope, the Government disappoints. It is time that we started owning the problems. A nation exists as a whole, not as Government and Opposition, which is merely an institutional arrangement for administering the affairs of the people in accordance with their wishes. That the present Government replaced a chaotic state of affairs by an orderly take-over of power in December last year is undeniable. That it was possible to get rid of Martial Law in four months’ time is something which everyone can justifiably feel happy about. That the present Government entered into negotiations with Opposition parties and was able to establish representative Governments composed of those parties in two of the Provinces showed political skill and vision.

More recently, the Government worked out a constitutional accord to which all parties are signatorles and this is a significant development. Finally, the withdrawal of forces as a result of the Simla Agreement is an important event and no one need hesitate to give the Government full credit for this.

This does not mean that the major problems are behind us. To claim that we have established democratic institution in the country is absurd. If anything, we have put these institutions, or whatever was left of them, under greater stress. To suggest that the reforms introduced by the government have even touched the real problem of the people is to delude ourselves.

The most unfortunate thing is that we have learnt no lesson from the disaster of December 1971. There is no sense of realism at all. the whole country has erupted into a frenzy over certain matters on which we do not have a decisive control. We continue to debate, declaim and harangue as if no structual or fundamental change has occurred in our situation. The Himalayas have seen many civilizations rise and fall. Let us not imagine that the furore we are creating will have any effect on their imperturbable serenity.

***

AMBASSADOR DECLARED PERSONA NON-GRATA

DAWN February 11, 1973 (News Report)

Huge arms haul from Iraqi embassy

IN a dramatic operation this [February 10] morning a party of Pakistan Government officials raided the Iraqi Embassy in Islamabad and recovered a large stock of arms and ammunition and guerrilla-warfare equipment – believed to be for distribution to “subversive elements” in Pakistan. Following the extraordinary step taken in the over-riding interests of state security,” the Government of Pakistan declared the Iraqi Ambassador and an Attache as persona non-grata. It also announced the decision to recall the Pakistan Ambassador in Iraq immediately, while preparing to lodge a strong protest with the Iraqi Government.

From the embassy premises, which, incidentally, belongs to Mr Ghiasuddin, Secretary-General, Ministry of Defence, 71 small and big crates had been recovered after three hours of search. The police had also cordoned the next house which serves as the Ambassador’s residence, and belongs to Mr. M.H. Sufi, Secretary, Cabinet Division.

***

ISLAMABAD AT ODDS WITH BALUCHISTAN, NWFP

DAWN February 17, 1973 (Editorial)

Disturbing developments

THE uneasy truce between the NAP-JUI associates and the PPP Government at the Centre, based as it was on arrangements that never seemed to work smoothly, has at last broken down. The NAP Governors of Baluchistan and the NWFP have been removed and the Baluchistan Government has been dismissed. The NWFP Ministry, finding that its position has become untenable, has resigned. These developments will not come as a surprise to observant students of the national political scene. The persistent propaganda drive started some time ago by the officially-controlled mass media against dissident political opinion in general and the NAP in particular was not after all an exercise in futility. When this campaign of denigration began to assume a very strident tone and to rise to an ever-higher crescendo, one could sense what was coming. The democrats with no party affiliations have to study the situation closely and dispassionately in order to be able to make an educated judgement on these developments. It is only thus that one can form an idea of where the country is heading for – an era of political consolidation in conditions of freedom and democratic tolerance or a period of political conflict in an environment of suspicion, distrust and petty-fogging about inessentials.

The removal of the two Governors, in the present context, will make sense only if it is followed by an effort to form alternative ministries. Now if such ministries are to enjoy a stable majority in the legislatures some members who were supporting the NAP-JUI Ministries will have to be seduced from their original loyalties. The process is unlikely to put a premium upon principled behaviour and the proprieties and decencies which sustain the parliamentary system.

With the traumatic experience of the political alienation and eventual secession of East Pakistan still fresh in our minds, we cannot exercise too much care in handling relations between the federation and the units and between one unit and another.

We do not count ourselves among the apologists of the NAP-JUI Ministries. We have often felt that they were more inward looking than they ought to have been. Also, we do not think that the adoption of the device of mobilising tribal lashkars was a proper thing for a government which was established by law and was sworn to uphold legality and the accepted norms of law enforcement. Nevertheless, we think the NAP-JUI Ministry could have been persuaded that the deployment of lashkars was neither proper in law nor necessary for its survival. The dismissal of the Ministry is an extreme step and does not augur well either for the development of healthy democratic traditions or for the growth of harmonious relations between the federation and the provinces.

***

THE NATION’S NEW CONSTITUTION

DAWN April 12, 1973 (Editorial)

Let’s turn a new leaf

THE National Assembly has gained universal applause and made the people’s hearts rejoice by giving the country a permanent Constitution which is based on the support of all parliamentary parties as well as on a consensus of the Provinces. The historic occasion marks the end of a tedious journey along a zigzag course, a journey marked by many a change of circumstances and quite frequent troubles. We were certainly unable to travel hopefully all the way, and indeed at times the caravan was in grave danger of losing its sense of direction and unity of purpose. But now that we have arrived, the hazards and troubles that we faced on our way are behind us and do not frighten us anymore. We have repeatedly emphasised in these columns the need for achieving the largest measure of agreement among the significant political forces on the foundational principles and the structure of the body politic and invited attention to the strife and divisiveness that could result from the enforcement of a Constitution adopted merely on the strength of majority support.

The Constitution that we have got after a lengthy process of discussion and disputation is not necessarily one which will produce ecstasies of joy all round. Neither is it absolutely necessary that it should. A constitution is not framed for the delight of the perfectionists. There are always people in every country who find that the Basic Law by which their country is governed is not the ideal document of their conception. In order to possess a reasonable chance of succeeding as the framework of government, a constitution must, as faithfully as possible, reflect the basic political principles by which a people wish to be governed and provide for institutions which can take care of the peculiar needs of the people of that country. Pakistan’s people have indicated their preference in unmistakable terms for a federal polity, a parliamentary cabinet system, appropriate safeguards of fundamental rights and an independent judiciary. The present Constitution contains features which can broadly be said to recognise those clearly stated preferences. The draft now adopted is certainly an improvement on the original one in several respects, particularly in regard to the quality of its bicameralism and in the safeguards that it offers of the citizens’ fundamental rights and the independence of the judiciary. To be sure democrats have clear and strong reservations about several features of the Constitution, such as the adequacy of its safeguards of individual liberty, the validity of the proposed concentration of powers in the hands of the Prime Minister and the protection against motions of want of confidence given to an incumbent of that office for a 10-year period.

Whatever its limitations, the Constitution has been acclaimed by a general agreement of opinion as providing a suitable framework for the organisation of our body politic. Now that this much is settled, our thoughts and energies must be directed towards ensuring that the Constitution proves a serviceable instrument for the realisation of liberty, stability and progress. The passing of the Constitution by a near-unanimous vote has dissipated the oppressive air of frustration that has hung over the country for the past many months. Here is a magnificent opportunity which both the Government and the Opposition must seize in order to end the suspicion and bitterness that cloud the political horizon.

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Editors and their policies

By Muhammad Ali Siddiqi

THE reaction to the so-called ‘Dawn leak’, which rocked the country last winter, amused Dawn staff members. Stung by Cyril Almeida’s scoop of Oct 6, 2016, the establishment thought it could fix the paper by bullying its owners. Little did they realise – in spite of having the services of a plethora of oafish intelligence agencies – that at Dawn things are not decided by the owners, and that news and views published in the paper are the sole prerogative of its editor.

From this point of view, Dawn is perhaps the only paper in Pakistan which has always has a professional editor, and the owners had not grabbed the editor’s slot – except once by force of circumstances – to make a mockery of editorial independence. Despite being a political family, the Haroons, owners of the Dawn media group, leave it to the editor to run the paper once the broad contours of policy are in place.

In my own little cosmos, and as a Dawn person who has cumulatively passed nearly half a century in the paper’s service, I do not recall a single time when the management bypassed the editor and called me directly to give me an assignment.

One reason for this clarity in the owner-editor relationship was the very personality of the man who founded Dawn. As Altaf Husain, the paper’s legendary editor, wrote, M.A. Jinnah “never issued any directive, never said ‘Do this’ or ‘Don’t do that’. In fact, he told me to study a given situation and form my honest and independent opinion on it, and then to write fearlessly what I thought – ‘no matter even if the Quaid-i-Azam is offended thereby’.” This tradition – of the editor and not the owner being the kingpin – has continued till this day, and the galaxy of editors we have had proved themselves worthy of the institution called Dawn.

Husain was a legend in his lifetime. His editorials jolted the government of the day, the ad denial making little difference to Dawn’s policy or to the panache of his editorials. The paper’s support for the Muslim League was categorical, and he harshly criticised non-ML governments. But, like sections of the political leadership, including Fatima Jinnah, he welcomed the military coup and supported the Ayub regime on a broad range of issues.

‘Ideology’ had no place in his scheme of things; his religion was Pakistan. For this reason, in foreign policy matters, he believed a close military alliance with America was in Pakistan’s interest, and despised the Left. However, when the US started pouring military aid into India following the war in the Himalayas, the national anger found an expression in his editorials. He then became a fervent believer in a strategic relationship with China, it being of no consequence to him that Pakistan’s north-eastern neighbour was communist.

In the presidential election, Husain supported Ayub and welcomed his election. But he did on occasion criticise the Ayub regime even when martial law was on. He joined the Ayub cabinet on the field marshal’s persuasion, but resigned after the 1965 war because along with Z.A. Bhutto he was among the hawks who disagreed with Ayub’s policies.

Between Husain’s exit and the assumption of editorship by Ahmad Ali Khan in February 1973, the paper saw four editors come and go, with designations changing under stress. Jamil Ansari was, of course, an excellent journalist and editorial writer, but, unlike his predecessor, his commitment to Ayub’s policies was total. While, unlike other newspapers, the news regarding Ayub‘s memoirs – Friends, not Masters – wasn’t a lead story, it was a page-one three-column affair, with extracts carried inside; the editorial was headlined, ‘The hero’s story of a heroic struggle’.

An indication of his policy was his instructions for us to be ‘cautious’ in writing headlines that could annoy the president even if it concerned Vietnam and reflected adversely on the American military. Ansari was sidelined when for the first – and let’s hope the last – time a Haroon became editor. The motive behind Yusuf Haroon’s assuming the office of Chief Editor was to thwart any government attempt to foist its own editor on the paper.

As a sub, I remember receiving instructions that appeared odd. The page layout was as dull as it could be, headlines became ridiculously small and we were told to avoid verb in headlines. So instead of ‘three killed in accident’ it was ‘death of three in accident’ or ‘passage of bill by NA’ rather than ‘NA passes bill’. In relaxed conversation with the newsroom staff Yusuf used to speak against Ayub, and ultimately had to flee the country. Ansari returned as editor and remained there till Altaf Gauhar became Editor-in-Chief.

As federal information secretary, Gauhar was the brains behind the draconian Press and Publications Ordinance, but suddenly he seemed to have discovered the virtues of free speech, as his criticism of ZAB’s policies show. Also adding to the Bhutto government’s discomfiture were two columns, more sarcastic than analytical, by S. R. Ghauri and Syed Najiulla. A versatile man, who later became an author also, Gauhar had to face prison, for the barbs in his editorials were too much for the government.

Unlike Yusuf and Gauhar, Mazhar Ali Khan was a dyed-in-the-wool progressive who knew journalism inside out and brought with him the valuable experience of being a former editor of the Pakistan Times. He abandoned Gauhar’s recklessness, and in his brief tenure ran the paper as a professional, and even though he differed with government policy on several issues, like his insistence on Bangladesh’s immediate recognition much to Bhutto’s annoyance, he did so by logic and reason. However, it was Ahmad Ali Khan’s quarter-century tenure that restored editorial stability to Dawn and gave a traditionally rightist paper a progressive thrust often branded ‘leftist’ by his critics.

Yet there was no seismic shift in policy, because Gen Ziaul Haq was a ruthless dictator, flogged journalists and used religion as a power tool. As Ahmad Ali Khan often told us, the challenge was to make use of such opportunities as were available and crawl rather than race. Thus, without frontally attacking the regime and challenging Zia’s usurpation of power, Dawn supported him on peripheral issues like Zakat and Salat, while opposing the pillars of his ‘ideological’ structure like Qazi courts; reminded the regime of Jinnah’s commitment to equality in law of all citizens and uncompromisingly stood for parliamentary democracy. The fact that Mahmoud A. Haroon, the paper’s owner, was Zia’s interior minister, made no difference to his policy.

A monumental decision on his part was to launch the weekly Economic & Business Review, which served as a forum for critically examining the regime’s policies, even if confined to business and finance. Gradually, as martial law gave way to ‘controlled’ democracy, Dawn opened its pages to a stunning variety of commentators ranging from Edward Said and Henry Kissinger from abroad to Dr Eqbal Ahmad, M. H. Askari, M. B. Naqvi, Omar Kureishi, Ayaz Amir, Ardeshir Cowasjee and Mazdak (Irfan Husain) at home.

His tenure also saw a technological revolution – from hot metal through photo offset to computerisation. By the time he bowed out, Dawn had emerged as an independent paper recognised for its critical yet sober journalism committed to a pluralistic society and statecraft. When he took over, Dawn was a six-pager; when he retired in 2000, it had four weekly magazines, with Dawn also having its Lahore edition. He also replaced the paper’s decades-old layout with a modified horizontal one.

Between Khan’s departure and Zaffar Abbas, the incumbent, we had three editors: Saleem Asmi, Tahir Mirza and Abbas Nasir. By no means should their contribution to Dawn be underestimated because of space constraints.

Saleem Asmi was the first Dawn editor from the news side, having served as news editor in Dawn and Khaleej Times, though like Mirza he too had a brief stint as a reporter. His grasp of the news was perceptive. One of his decisions was to publish Osama bin Laden’s interview by Hamid Mir, even though he was a non-staffer, because the interview contained hard news about nuclear technology. Gen Pervez Musharraf felt piqued because he was in America at the time. Asmi also paid attention to art coverage. Of the two magazines he left behind, The Gallery, as the name suggests, concerned art; the other was Books and Authors. Asmi also launched Dawn’s Islamabad edition.

Mirza had already made clear he wouldn’t be there for more than three years, because he was a writer and felt his talents circumscribed as editor. He was on his toes when the earthquake struck Pakistan and Azad Kashmir, and I think the quality of Dawn’s coverage and comments was better than that of any other daily. A man of principle he resigned his petrodollar job with Khaleej Times as executive editor because the owner wanted him to write a ghost column for him.

Abbas Nasir had to operate in a totally different Pakistan where a multi-media world of cyber journalism with 24-hour TV news, FM radio and websites were forcing newspapers to think afresh. He made dawn.com what it today is by overhauling what critics used to call ‘yesterday´s newspaper on today’s web’. He also made the Dawn team realise that it would be absurd to merely report what TV had told our readers 24 hours earlier. So the print version had to have a dug-out bit of cerebral background to give the breakfast reader something different from the electronic channels’ ocular coverage. Nasir also came out most categorically in favour of civilian supremacy, included new writers for op-ed pages and mobilised the reporting side to come up with investigative stories which TV channels later followed.

While I have in my humble way given a brief assessment of our editors, I cannot but remember those countless unknown soldiers whose names the readers never knew but who helped the editors make Dawn what it is today. They are too numerous to be mentioned. In natural calamities or man-made disasters, street battles or war zones, the Dawn person has been aware of the fact that he/she is serving a paper founded by the man who founded Pakistan.

There is charisma in the word Dawn. In April 1950, the paper’s name was changed to Herald, inviting public wrath. The moniker Dawn returned, and Altaf Husain wrote in a page-one double-column box in colour, headlined Dawn zindabad: “I give them back their Dawn. No one is happier today than I. [...] Dawn was never dead. It was not intended to die. It shall never die.”

The writer is Dawn’s Readers’ Editor

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature

Bhutto on the implementation of the Interim constitution of 1972

Bhutto and Indira Gandhi on the repercussions of the Simla Agreement (1972)

Abbas Nasir on the challenges of being the editor of DAWN

Click on the buttons below to read more from this special feature