Pakistan: The lesser-known histories of an ancient land

The first people

Long before the emergence of the great Indus Valley Civilisation on the banks of River Indus 5,000 years ago, the earliest known people to make present-day Pakistan their home were the Soanians.

They were hunter-gatherers who lived 50,000 years ago. Archaeologists gave them this name because their tools, pottery, and fossils of various wild animals were found in Soan Valley near Islamabad, the capital of present-day Pakistan.

Still standing

16 stones, believed to have been erected almost 2,500 years ago by a civilisation of sun-worshippers, still stand in the Swabi District of present-day Pakistan. Each stone is approximately 10ft tall. Archaeologists believe they may be pillars of an ancient sun temple.

Alexander attacked in Multan

After conquering the vast Persian Empire, the armies of famous Greek warrior-king, Alexander, entered what today is Pakistan. In 326 BC (or over 2300 years ago), his campaign received a severe blow when he was wounded by a poison arrow on the walls of a citadel in Multan. Though he did not die, he soon fell sick and had to abandon his Indian campaign.

The citadel where Alexander was wounded was being defended by the Brahmin Malli tribe. Today, on the site of the citadel stands the magnificent tomb of Sufi saint Shah Rukh-i-Alam. It was built in 1324 CE by Muslim king, Ghiasuddin Tughlaq.

Born in Swat

Padmasambhava, the founder of Tibetan Buddhism (also called ‘the second Buddha’), was born in the 8th century CE in an area which today lies between Lower Dir and Swat District in modern-day Pakistan.

After ruling as a Buddhist king in the area, he is said to have abdicated his throne and travelled to Tibet to introduce Buddhism there. He is still revered as a sacred figure in Tibet.

Barbarian rule in Sialkot

Huns were fierce nomads in Central Asia. In the 5th century CE they managed to conquer vast lands in Europe, Central Asia and ancient India. They entered India through present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province in Pakistan.

Huns were fire-worshippers. A Hun warrior, Mehr Gul (Sunflower), established himself as king here. He ruled from his capital in what today is Sialkot in Pakistan’s Punjab province. His rule was brutal and he was defeated and removed by a confederacy of Hindu Rajput rulers from Rajasthan (in present-day India) and Multan (in present-day Pakistan).

Qasim’s Landing

Armies of 8th century Arab general Muhammad Bin Qasim invaded Sindh from the sea. The army landed on the shores of Debal. Debal stretched all the way to the ancient city of Banbhore in Sindh from where Qasim’s forces defeated the armies of Brahmin king, Raja Daher.

Debal today is the Manora area in Pakistan’s metropolitan city, Karachi. An ancient Hindu temple can still be seen in the background.

A 5-star battle

Central Asian Muslim king Mahmud Ghaznavi invaded India from Afghanistan. In 1001 CE, he marched on to Punjab after defeating Hindu king, Jayapala, in a battle in what today is Peshawar in Pakistan. It was a fierce battle. Jayapala set himself on fire after his army was defeated.

In 1971, when a site in Peshawar was being dug up to lay the foundations of Hotel Intercontinental (now called Pearl Continental), workers found hundreds of old human, elephant and horse bones. Archaeologists believe that the ground on which the hotel was eventually built was the site of the fierce battle between the armies of Ghaznavi and Jayapala.

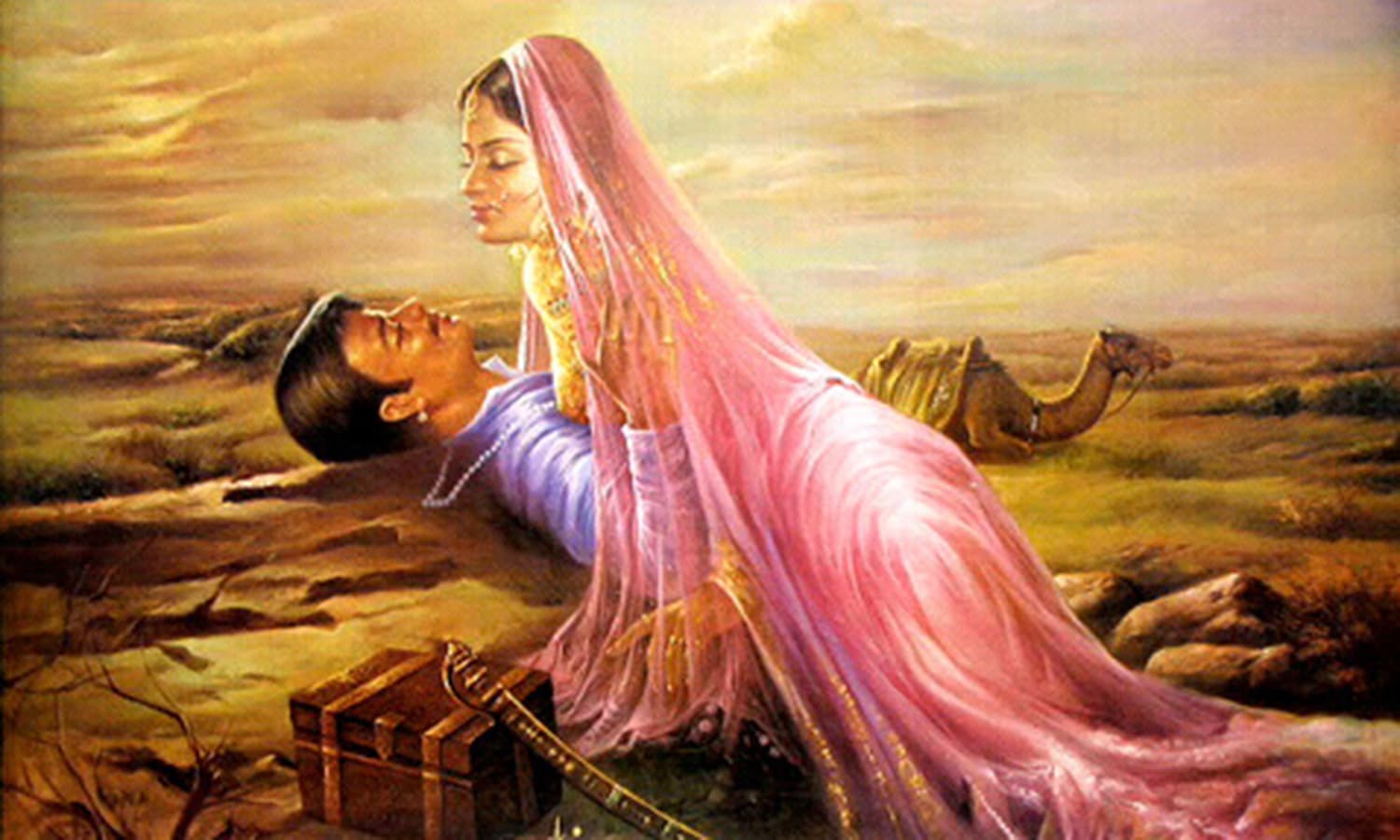

Sindh’s romantic rise

Famous romantic folk-tales Sassi-Punnu, Umer-Marvi, and Soni Mahiwal were all first conceived during the powerful Soomra rule in Sindh between 1024 and 1351 CE. During this period, Sindhi language and culture were greatly enriched. The Soomra dynasty folded in the mid-14th century when the last Soomra king was defeated by Allauddin Khilji, the second king of the Khilji dynasty ruling from Delhi.

Many of the folk-tales created by Sindhi storytellers during the Soomra rule inspired the famous 17th century Sufi saint, Shah Abdul Latif, who reproduced them in writing when he came and stayed in Sindh. It is through him that these tales also reached Punjab.

The war which ended the Soomra dynasty in Sindh was fought over a princess. Her name was Bilquees Bhagi. The Soomra dynasty had friendly relations with the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad. But when the power of the Caliphate began to weaken (due to attacks by the Mongols), the Soomras tried to rekindle their links with the Delhi Sultans.

Allauddin Khilji asked Soomra king, Doda, to send Bilquees to him as his bride. Doda refused and went to war with the Sultan. After Doda’s defeat, Bilquees is said to have vanished. Most believe she committed suicide. Her body was never found.

Medieval safari

Wild animals were aplenty in the region, which today is Pakistan, when Mughal king Babur invaded India from Afghanistan. A painting of him hunting rhinoceroses in the outskirts of Peshawar appears in his autobiography Baburnama. Babur founded India’s Mughal Dynasty in 1526 CE.

Rhinos, elephants, lions and cheetahs were common all across what today is Pakistan. Out of these, rhinos, elephants and lions became extinct here from 18th century onwards, mainly due to hunting, human encroachment and climate change. Cheetahs became extinct in the 1950s.

Paradise lost

Lahore’s famous Shalimar Garden was built in 1641 CE during the rule of fifth Mughal king, Shah Jahan. The land on which it was built belonged to ‘Mian’ family belonging to Punjab’s Arain tribe. The family was given the custodianship of the Garden by Shah Jahan.

The Mian Arian family retained the custodianship of the Garden for over 350 years until the site was taken over by the government of Pakistan in 1962 during the Ayub Khan regime.

Between 1965 and late 1970s, the Shalimar Gardens hosted a number of high-profile functions and receptions. It was also a favourite tourist resort. However, from the 1980s onward, the Garden began to deteriorate. Since 2001, it has been placed on UNESCO’s list of Endangered World Heritage Sites.

A flood of crocodiles

In a large pond adjacent to an old shrine of a Sufi saint in the Mangopir area of present-day Karachi are dozens of crocodiles. Legend claims that they have been staying and breeding here ever since a Sufi saint settled in this area in the 13th century CE.

19th century British colonialists, when they annexed Sindh, were fascinated by the phenomenon. They would go up to the shrine and watch the crocodiles being fed.

Scientists and archaeologists have found crocodile bones in the area which are actually older than 13th century CE. Scientists believe the bones may actually be 5,000 years old. They also added that the crocodiles were carried here in an ancient flood thousands of years ago that originated in what is called Hub and is situated in present-day Balochistan area. The crocodiles were stranded in Mangopir when the floods receded. They have been staying and breeding in this pond for centuries.

Even today, the crocodiles here are largely docile and are regularly fed by pilgrims who continue to visit the shrine.

The late blooming of Eid Miladun Nabi

Eid Miladun Nabi is celebrated on the birthday of Prophet Muhammad (Peace be Upon Him). He is said to have been born in Makkah in the late 6th century CE. Eid Miladun Nabi is a colourful and joyous occasion, which is observed by most Muslims - except for some Muslim sects and sub-sects. Eid Miladun Nabi is said to have first gained prominence in the 11th century CE in Egypt under the rule of the Fatimid dynasty. By the 13th century, it was being celebrated in Turkey during the rise of the Ottoman Empire.

In the subcontinent, Eid Miladun Nabi became a lively and boisterous occasion in the 16th century CE during Mughal rule. In the context of the area which is present day Pakistan, Eid Miladun Nabi was most actively observed in Punjab and Sindh during British rule. It was declared a national holiday by the government of Pakistan in 1949.

The Africans of Karachi

Lyari is one of the oldest areas of Karachi. The area grew from a community of fishing villages and began to expand in the 18th century CE. Lyari has always had a large community of Sheedis or Sidis. They are also known as Afro-Indians and/or Afro-Pakistanis.

The Sheedis were first brought from Africa to South Asia as slaves by Portuguese traders in the 16th century CE. After they gained their freedom during the start of British rule here, most Afro-Indians settled in Gujarat (in present-day India) and in the Makran area of Balochistan, and in Sindh in present-day Pakistan.

Sheedis who have lived for generations in Lyari were brought from Central and Southern Africa. According to some recent DNA tests of Lyari’s residents, scientists suggest that a majority of Sheedis once belonged to the Bantu-speaking tribes of Africa. Most of them converted to Islam.

Lyari has always been a working-class area. It started to become a slum in the 1940s. Crime and drug addiction began to increase in the area from the late 1960s. Lyari then became a hotbed of anti-government activism during the Ziaul Haq dictatorship in the 1980s. In the 1990s, violent gang warfare erupted here which lasted until 2015.

Unlike the rest of the country where sports such as cricket, hockey and squash have been popular, Lyari has produced some of the best Pakistani boxers and footballers.

The first cinema

One of the first cinemas in India was built in Karachi, Star, which was erected in 1917. It lasted until the 1940s before being pulled down.

In the 1970s, another Star cinema was built on the site where the original one had stood. The new Star cinema stood adjacent to Bambino cinema.

When Pakistan’s film industry collapsed in the 1980s, this Star too was closed down.

Bruce’s Quetta

When Quetta came under British rule in 1877, a British architect called Mr Bruce designed a street in that city which was said to be one of the most beautiful in the region. Called Bruce Road, it was lined up with high-end shops. It also had a pub simply called Bruce’s Inn which had Mr Bruce’s image on its signboard. The pub was often frequented by the British and local elite of the city.

The older buildings here were destroyed in an earthquake which razed the city of Quetta in 1935. However, until the early 1970s, there was still a tailor shop and a liquor store here both named after the enigmatic Mr Bruce.

Once upon an oil field

In 1915, oil was discovered in Khaur - an area which today is in the Attock District of Pakistan. British drilling companies believed that the area had huge reserves of crude oil. In fact, in 1938, when vast reserves of oil were discovered in Saudi Arabia, the British were sure that the oil fields of Khaur would be able to produce as much.

The oil fields of Khaur did produce oil but not as much as expected. When the area became part of Pakistan, the Pakistan government continued to drill more oil wells in Khaur. The last such well was drilled in 1954. But by then the oil in the grounds of Khaur had been exhausted.

Cleaner days

In the late 19th century when a plague struck Karachi, British colonialists (who had annexed the city in 1839), devised a hectic plan to cleanse the city. By developing the city’s creaky infrastructure and building a complex sewerage and garbage-disposal system, the British were successful. By the 1920s, Karachi was being described as ‘the Paris of Asia’ and it became one of the cleanest cities in South Asia. The roads were regularly scrubbed with water.

Even after Karachi became part of Pakistan in 1947, the practice of cleaning the streets and roads of the city with water continued. The practice stopped sometime in the mid-1960s.

Overcrowding in the 1970s created larger slums and by the mid-1980s, the city’s old infrastructure (which had not been improved) began to break down. The city fell into a crime-infested, frenzied mass of chaos.

Karachi also began to face a serious garbage-disposal problem from the late 1980s. This problem has continued to worsen.

The forgotten tides

One of the main threats faced by all cities by the sea are tidal waves generated by an earthquake or a raging storm. Over the years, Karachi has been lucky to have only received the fading tale of storms. However, the lesser-known fact is that the city has actually been hit twice by deadly tidal waves.

The first one hit the city in 1944 due to an earthquake in the waters of Makran coast. Newspapers of the time reported that as the earth shook, a 40ft tidal wave smashed the shores of the city. Over 400 people lost their lives. The water also made its way in the more populated areas of central Karachi.

In December 1965, an abnormal winter cyclone developed in the Arabian Sea. It generated massive waves which crashed into Karachi and completely submerged the entire southern end of the city. Newspaper reports suggest that over 10,000 people lost their lives. The cyclone which created this devastation was called Cyclone 013A.

A tent regime

When Pakistan gained independence in 1947, it was extremely short on land and other resources, especially when millions of Muslims migrated to the new country from India. Vast refugee camps were set up to accommodate the refugees. But the refugees alone did not live in the tents in these camps. Open fields in Karachi and Lahore were covered with tents which were also used by government officials and bureaucrats as offices.

Many government officials, including some ministers, and bureaucrats worked from these tents until new office buildings were built or acquired in the early 1950s. Pakistan’s first stock exchange in Karachi was also situated in one such tent.

Angry wives

When the 1956 Constitution declared Pakistan an ‘Islamic Republic’, many newspapers reported that the wives of most parliamentarians accused their husbands of hypocrisy. Cartoons began to appear in the papers satirising the situation.

In 1958, when military chief Ayub Khan and President Iskandar Mirza imposed the country’s first Martial Law, they suspended the Constitution, claiming that it had been used by cynical politicians ‘to peddle Islam for political gains'. The country’s name was changed to Republic of Pakistan.

The name was changed back to Islamic Republic of Pakistan in the 1973 Constitution.

A Little Israel in Karachi

Jews in South Asia first arrived in the 19th century. Most of them came to cities such as Karachi, Peshawar and Rawalpindi to escape persecution in Persia. By the 1940s, Karachi had the largest concentration of Jews, with most of them living in the city’s Saddar and Soldier Bazar areas.

Most Jews living in Rawalpindi and Peshawar began to leave after the creation of Israel in 1948. The last Jewish family to leave Pakistan was in the late 1960s. It had been living in Karachi for decades and its members were all registered Pakistanis who had supported Mr Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan.

The drowned town of Azad Kashmir

In 1967, the government of Pakistan completed the construction of the Mangla Dam. It remains to be the 7th largest dam in the world. Built on Jhelum River in the Mirpur District of Azad Kashmir, the dam’s construction caused the ‘controlled flooding’ of some villages and one major town. They were completely submerged underwater.

The inhabitants were all evacuated and compensated well before the submergence. For years, some structures of the drowned town would slightly emerge during low tide. Some of these structures can still be seen, but today they appear a lot more rarely than before. Curious folk still dive in this section of the river to investigate the remains of the drowned town.

The phenomenon inspired the finale of the popular Pakistan television serial, Waaris (1979). In the final episode of the series, a conservative and traditionalist feudal lord, Chaudhry Hashmat, decides to remain inside his ancestral house as his vacated village begins to submerge under water due to the construction of a dam.

The national dress

The shalwar-kameez (for both men and women) is often considered to be Pakistan’s national dress. The fact is, this wasn’t always the case. Until the early 1970s, Pakistan’s national dress (for men) was actually the shervanee.

Until the late 1960s, urban white-collar Pakistanis and politicians were expected to turn up to work either in a shervanee, a three-piece-suit or in shirt and trousers. Shalwar-kameez was not allowed.

Even college and university students were expected to turn up in a shervanee or a three-piece-suit during special occasions and functions.

The shalwar-kameez only got traction in urban Pakistan when the populist Prime Minister, Z. A. Bhutto (1971-77), began wearing it at mass rallies. Even though he was also known for his taste for exquisite and expensive three-piece-suits, he almost always appeared in shalwar-kameez at large public gatherings. The shalwar-kameez became a populist political statement of sorts and was then labeled as awami libaas (people's dress).

In the 1980s, however, during the conservative dictatorship of Ziaul Haq, the shalwar-kameez somehow began being associated with the Muslim faith. This was strange because, according to famous archaeologist and historian, Ahmad Hasan Dani, the first ever variants of the shalwar-kameez were actually introduced in this region almost 2,000 years ago during the rule of Buddhist king, Kanishka, in present-day Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

The tikka inventors

Most Pakistanis when they order a chicken tikka outside Pakistan get small boneless barbecued pieces of chicken. In Pakistan, a chicken tikka means either a whole barbecued leg piece (with thigh) or a chunky chest piece of a chicken.

Very few know that this version of the chicken tikka is available in Pakistan alone. In fact, it was invented by the chefs of the once famous Cafe de Khan in Karachi in 1960. The cafe offered this unique version of the chicken tikka which it then encouraged to be had with a paratha and a chilled Coke or a pint of beer.

People loved it and ever since 1960, this version of the chicken tikka has been popular all across Pakistan - and, for decades, only in Pakistan.

The casino

On the site where Pakistan’s largest shopping mall stands today (in Karachi’s Sea View area), there was once a stylish building erected between 1975-76. It was a widespread structure which was supposed to be the country’s first major casino.

The land for it was allotted by the Z.A. Bhutto regime to an entertainment business tycoon, Tufail Sheikh, who already owned a hotel and a nightclub in the city. The idea was to construct a giant casino to attract rich Arab sheikhs to Karachi after a civil war had broken out in Beirut. Beirut, before the war, had been a favourite haunt of rich Arabs and Americans frequenting its casinos.

The casino was completed in April 1977. It was an impressive and imposing structure with a huge hall where gambling tables and machines were placed. The casino also had bars, restaurants, guest rooms and a nightclub. The Bhutto regime was expecting a windfall of foreign exchange and a booming entertainment and hoteling industry to emerge around the casino.

In March 1977, the Bhutto regime got cornered by a violent protest movement by a right-wing alliance of opposition parties. In April, he agreed to their demand of closing down nightclubs, gambling at horse racing and the sale of alcoholic beverages (to Muslims). Ironically, these sudden bans were imposed on the day the casino was to be inaugurated.

Karachi already had the most number of luxurious hotels in Pakistan. Anticipating a flood of visitors from oil-rich Arab countries, Europe and the United States after the emergence of the casino, a huge hotel too began to go up in the city’s Club Road area. It was to be the Hyatt Regency and was one of the biggest in the region.

There were already two 5-star hotels on Club Road (Intercontinental and Palace) and two nightclubs (Playboy and Oasis). But as the casino’s inauguration was halted, the construction of the hotel too stopped.

In July 1977, the Bhutto regime fell to a reactionary military coup. The doors of the casino were locked, even though Mr Sheikh still owned the land and the building. In the 1990s, the casino building was turned into a recreational spot for children, with rides and all. In 2011, the building was bought over by real estate developers. It was finally torn down and a massive shopping mall was erected in its place. Many believe that had the casino survived and functioned as planned, Karachi would have become what Dubai is today.

Pakistan’s Polish soldiers

As the situation in Poland got worse during the Nazi occupation and then after World War-II, 45 Polish officers and scientists flew to Pakistan in 1948 and signed a 3-year contract to serve in Pakistan’s nascent armed forces.

The most prominent was a brilliant aeronautical engineer, Władysław Józef Marian Turowicz.

Turowicz joined the Pakistan Air Force as chief scientist and helped set up technical institutes to train fighter pilots and develop new aeronautical technologies. In 1952, he was made Wing Commander in the Pakistan Air Force and in 1959 he was promoted to Group Captain. The very next year he became Air Commodore.

In 1966, he convinced President Ayub Khan to develop Pakistan’s space programme. He was teamed up with future Nobel laureate, Dr Abdus Salam, to develop rocket technology for Pakistan. Salam and Turowicz’s work lay the foundation of Pakistan’s missile technology.

Turowicz stayed in Pakistan with his wife and two daughters, while rest of his Polish colleagues returned to Poland. His third daughter was born in Pakistan and became a gliding expert. She trained the cadets of Shaheen Air in the 1990s.

Two of his daughters married Pakistanis and the third one married an East Pakistani (now Bangladesh). Turowicz died in a car crash in Karachi in 1980.

He was given a number of state and military awards in Pakistan: Sitara-i-Pakistan (in 1965); Tamgha-i-Pakistan (1967); Sitara-i-Khidmat (1967); Sitara-i-Quaid-e-Azam (1971); Sitara-i-Imtiaz (1972); and the Abdus Salam Award (1978).

All photos are taken from Archives 150