Enabling the differently abled

From schooling to finding reliable healthcare and then searching for a job that provides dignity as well as decent pay, persons with disabilities often find the deck stacked against them

Blinding indifference

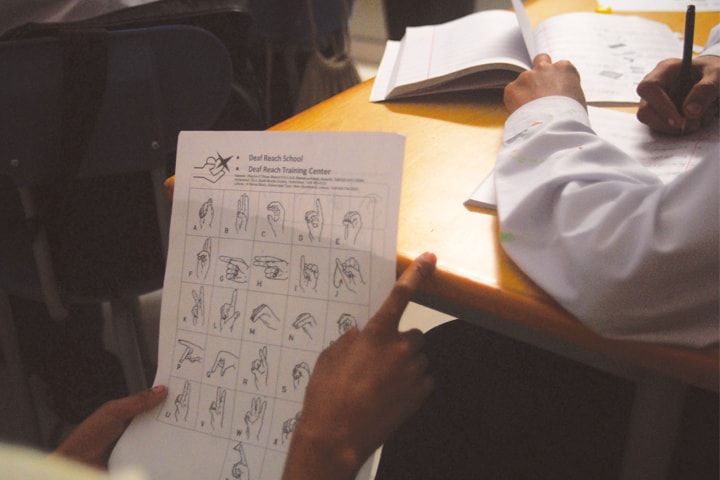

Despite being the preserve of the government, public-sector education for special people is conspicuous by its absence

|

| Photos: Pakistan Disabled Foundation |

Despair often overwhelms Ataullah when he looks at his young son Gul, who lags far behind in all developmental milestones a child is supposed to achieve very early in life.

The young boy, the eldest of the four siblings, spends most of the day lying on a charpoy and all his personal needs are taken care of by the family.

“At times, I cry when I see that he hasn’t even learnt to feed himself in 11 years. I still remember how happy I was when he was born; I thought he would share my burden and help the family. But now, it seems that he wouldn’t even be able to support himself,” he regrets.

Working as a driver in the small town of Kunri, part of Umerkot district in Sindh, Attaullah tried his best to seek treatment for his mentally and physically challenged son as soon as the family realised that he was not behaving normally.

|

But the doctors he consulted in Hyderabad and Karachi neither offered the family a picture of what the future holds for Gul nor guided them about any facility that could offer help to their child. “They couldn’t diagnose his illness and only told us that he suffers from some kind of muscular weakness that might affect him for life,” he recalls.

According to Ataullah, he is not alone in having a special child in his neighbourhood and there are a few families that he knows who are facing similar predicaments.

“All these children miss out on peer activities and are kept within the confines of the home all day. Poverty coupled with illiteracy and ignorance leave us with hardly any option,” he laments, adding that though he has heard of schools meant for special children, there is no such facility in his district.

It’s not just the rural areas where parents have absolutely no support available for their children who are facing mental and physical challenges. Similar stories exist in the country’s urban parts that are neglected and plagued with poverty, while the conditions at most special schools, especially those operating in the public sector, leave much to be desired.

|

“In Sindh, there is no facility in the government sector to help the mentally-challenged children improve their lives and learn skills,” claims Riaz Memon, who heads the Sindh chapter of the Pakistan Association of the Blind and is posted as a Braille instructor at the Chandka Special Education Centre for Visually Handicapped Children. “As for the blind, no Braille books are available for them in Sindh, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Punjab is the only province that has a press for printing books in Braille.”

Memon argues that mentally challenged children were the most neglected in government priorities, and there were only a handful of facilities for them in the entire country. According to him, there are more than 80 government schools for special children in Sindh, but most of them are in poor condition facing a dearth of trained teachers, often appointed on political basis.

“Most government special schools either offer education till class five or eight. Hence, those children wanting to pursue studies have to face a lot of hurdles,” he says, adding that there is no institution to train teachers in special education in the province.

|

Sindh has a department for special education, but none of its officials were available for comment despite repeated attempts.

Meanwhile, conversations with parents of special children show that one of their biggest challenges is to accept the fact that their child is special and then to find the support on how to handle him or her.

“The frustration and stress parents go through during the initial years is huge and there is no help available to them in most cases.

“A lot of time is wasted in late diagnosis, delayed acceptance by parents and due to lack of awareness and absence of support groups and networks for such parents in our society.

|

“Then, there are parents who wonder why they should spend money on a disabled child who has no future? ” says Sidra, mother of a teenage girl with Down’s Syndrome.

In her opinion, finding the right school according to the needs of the child (as he or she could have one or multiple disabilities of varying levels) and parents’ financial position is a major problem. Facilities in the government sector are limited and are known to offer poor quality services while private schools are being run like a money-making business.

“For instance, I can’t let my daughter having slight-to-medium level learning issues go to a school where most children have severe intellectual disabilities. I would fear that she would also become like them instead of building on her abilities,” she argues.

|

On the other hand, Dr Jamal Ara, an endocrinologist presently serving at the United Medical and Dental College, Korangi and mother of the renowned painter with Down’s syndrome, Mariam Khan, says that the world has moved away from the concept of building separate facilities for special children, and the focus now is to help such children attain knowledge and skills at regular schools.

Most special children, she contends, have mild to medium form of mental and physical disabilities that could be easily managed by trained, resourced teachers posted at regular schools.

“This is an age of inclusive education as it helps special children develop confidence and skills at par with their abled peers who also learn to be kind, to help and share at an early stage of life,” she says.

Such notions seem fanciful if not a distant dream to those who have no other choice but to turn towards public-sector education for their children’s schooling.

Parents, among other things, complain of an acute shortage of trained teachers especially at government-run schools, lack of specialised learning equipment for the disabled, and the absence of transportation that could pick their kids from home and drop them back.

|

“My daughter has severe muscular weakness and can’t bend her knees but she, along with other children, is deprived of a comfortable sitting area. There is no rest area at the school and children with different disabilities are forced to sit for hours,” says Fatima having a mentally and physically challenged teenage daughter enrolled to a government school for special children in Gulistan-i-Jauhar, Karachi.

Her troubles don’t end here. According to Fatima, the government school has male-only attendants that are hired by parents at a monthly fee of Rs3,000 to facilitate their children.

“Not every parent can afford that. Second, being a mother of a teenage girl, I have reservations over having male attendants that are also required to carry disabled children, including girls, in their arms to take them to the washroom or help them get into the van,” she says, voicing her concerns.

The government schools for special children, she believes, are as ill-equipped as any other school being run in the public sector. “Children are given long breaks so teachers can spend their time gossiping. There is no female staff to change children’s pampers and mothers are called from homes to do that., What about mothers living at distant places?” she asks.

Fatima, a resident of North Karachi, couldn’t find a school for her visually impaired daughter, also affected by autism, for two years. Her problems, as well as of the child, were compounded since she had no understanding of how to handle her special baby.

“For a long time, I used to feed Tooba diluted food as she wasn’t able to chew or suck properly. Later, I hired a girl trained in special education who helped my child learn how to eat solid foods,” she says, adding that now her daughter was now in a private school where teachers could handle students with learning disabilities.

The Disabled Persons (Employment and Rehabilitation) Ordinance, 1981

The “Disabled Persons (Employment and Rehabilitation) Ordinance” was enacted in 1981 as a presidential ordinance. This law was promulgated during the “International Year for Disabled Persons” in 1981 to provide support to the disabled persons in finding employment in government as well as commercial and industrial establishments. Government of Pakistan has also ratified ‘ILO Convention on Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment of Disabled Persons’. It has also ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

The Ordinance provides to create Funds and establish the National Council for the rehabilitation of Disabled Persons; and it made mandatory to employ two per cent disabled persons in public sector. The National Council’s Rules were notified in 1983. The National Council for the rehabilitation of Disabled Persons: The Council was mandated to formulate a policy for the employment, rehabilitation and welfare of the disabled. Additionally, it has the mandate to conduct the medical examination, treatment and survey on persons with disabilities.

Section 10: The “Disabled Persons (Employment and Rehabilitation) Ordinance 1981: (DPO-1981): Is applicable to any establishment, whether government, industrial or commercial, in which the number of employees at any time during the year are at least one hundred (or to simplify it; which employs at least 100 workers for the whole year).There must be two per cent quota for disabled persons in the above mentioned organisation.

Section 11. Establishment to pay to the Fund: An establishment which does not employ a disabled person as required by Section 10 shall pay in to the Funds each month the sum of money it would have paid as salary or wages to a disabled person had he been employed.

Source: www.accesstojustice.pk

The special parts of our lives

By Fawad Hasan

Mehtab Fatima blames herself for the everyday struggles of her 24-year-old son, Hasnain Rizvi, who developed cerebral palsy soon after his birth. “Let me be straightforward: it is my punishment for having laughed and teased special children and their families when I was young; God has put me in testing times now,” she argues.

Hasnain was born very healthy, narrates his mother, but due to a lack of oxygen, he developed cerebral palsy. He cannot speak, but he understands when people come to see him and pretend to sympathise with him. Some even have the audacity of saying, “God bless us all; please save us from this disability” before Hasnain and his family.

|

| File photo by White Star |

“What irritates me is that people do not understand that even if Hasnain is not ‘normal’, he does understand when people act in such disgusting ways,” says Fatima.

“Hasnain not only understands if the guests say anything horrible about him, he also reacts aggressively. Sometimes he cries, and it always breaks my mother’s heart,” adds 20-year-old Askari Rizvi, Hasnain’s younger brother.

|

As Hasnain rests in an adjacent room, Askari narrates that it was only as a conscious adult that he began understanding Hasnain for who he is. “In my childhood, I used to make fun of special people, including my brother. But now I understand that persons with disabilities are also human and have every right to live. It is our responsibility to help them with their living,” he says with regret in his voice.

Mehtab Fatima has done everything possible for her special child, now a grown-up man, who can only lie in bed all day long. She takes care of everything; from feeding her special son to bathing him, even keeping troublemakers away from him.

“I have provided him everything he needed; he has a separate room with air conditioning, uninterrupted power supply, just to ensure that he does not get aggressive, uncomfortable or irritated by anything,” she says.

Beyond making these arrangements, there isn’t much else Fatima can do. “My husband often says to me jokingly that when you die, your coffin will be followed by your son’s coffin, because your life is intertwined with his. I am Hasnain’s lifeline and when I die, Hasnain will die with me too.”

“My child was two when I finally got to know that he is not normal. By the time he was four, all he could say was Mamma, Papa, Hello and Allah,” says Tehmina Ahmed*, a 45-year-old government school teacher and mother to four.

“Farrukh was my third child. He was born normal. When he was about to turn two, he had had extreme fits. That damaged his brain which now couldn’t function properly. He is unable to understand things well. He can’t speak much,” she narrates.

Farrukh always looks down when he walks, which makes him vulnerable to falling or tripping over things, but it is in part to never have or maintain eye contact with anyone else. According to Tehmina, much of this is due to a lack of confidence — bred not by the family but reinforced by ideas and attitudes around him. This low self-esteem has been eating at him from the inside for years.

Tehmina admitted her son to a renowned school for special children, but in her opinion, their administration did not really put in much effort with the children enrolled. “All they would teach my son was alphabets and numbers,” she says. “That did not help my child grow up mentally. And that is why I decided to change schools.”

|

But getting her son admitted to a regular school, and then keeping him there, was an exhausting experience. After two years of persistent complaints by the school administration, Tehmina was asked to stop sending Farrukh to school, as he was unable to grasp things other pupils could easily do.

“I then decided to admit my child to the same school where I work so that he could remain in sight,” says Tehmina. By that time, Farrukh was already eight years old. Five to six years of his life had been wasted because he did not receive the education that he should have or needed to.

But when Farrukh started going to school with his mother, she started meeting with stiff resistance at the hands of friends and colleagues.

“When I asked a colleague to take extra care of Farrukh in class, since other students might not be able to understand him or his condition, she retorted that a special child couldn’t possibly study in this school and that I should remove him. I simply asked her a question: what would you have done had Farrukh been your child?”

Today, when Tehmina makes her child sit with her and study in class, other students surround them, peeping in from the windows of the classroom, and making a cheeky or offensive remark or two. She prefers sitting in after school hours to avoid any nastiness. “After all, these kinds of children come from the same society which does not accept children like mine. What else can I expect?”

Tehmina is hopeful that her child will one day begin learning things fast. Farrukh’s doctor has imbued her with immense hope, which strengthens her determination to carry on living.

“No one understands that these kids, such as mine, are a lot more sensitive who want to love and be loved,” says Tehmina, with a heavy voice, yearning for a world where her child is accepted with all his weaknesses and sensitivity.

But will that day come when society accepts her child?

“I think before society, such kids need be accepted by their own family, their siblings and parents. As for Farrukh’s case, he was considered a burden by my husband. What do I expect from other people?”

In such circumstances, it is only human for a mother to break down.

“Farrukh is always the first one in the family who comes to me, cuddles me whenever I am giving up on life. He always stutters: ‘Mama, tell me what happened? Who made you cry?’”

For Zain Ali respect, or lack of it, is at the heart of the matter.

“I lost my eyesight when I was 14. Life changed drastically, I thought it had ended,” says Ali, now a 24-year-old student at the University of Karachi’s English Department.

As he keeps talking, sitting on the stairs of his department, people peep with inquisitive eyes, appearing surprised as to what he is discussing with such sheer concentration. Ali fortunately cannot see their intrusive curiosity.

When asked what worries him about the future, he says that the pursuit of a livelihood after graduation keeps his mind engaged.

“Lately, a private bank and a fast food chain company have introduced jobs for visually-impaired persons. This is indeed a laudable initiative. At least, they are doing their bit. But tell me, once we have completed our Masters, are we expected to go and apply for a waiter’s job?”

Indeed, the options for dignified employment are far and few.

“Kenneth Jernigan of National Federation of the Blind was right in saying that the themes which have been imbued in literature and thus in society about blind people are blindness as total tragedy; as foolishness and helplessness; as punishment for sin; or as an abnormality. It is for these varied reasons that society never accepts us. Even in literature we, the blind people, have been portrayed as persons who are not normal,” laments Ali.

Perhaps it is because of the everyday struggles of the differently abled that young mother Neha* was squeezed in the trickiest of dilemmas: to give birth to a child already diagnosed with microcephaly or to abort the process. It was her first pregnancy, and that too, after a lot of years spent in prayer.

Neha knew this dilemma would shape her life for many years; it was a decision that was going to be uncomfortable either way. She eventually chose the latter option, to abort, in part because she didn’t have the strength of bringing that child into the world and caring for him, and in part to save the unborn child from a life of misery.

“I was not as strong to live my life raising that child,” says Neha. “It would have meant living and dying at the same time, in the everyday struggle of raising a child with an abnormality. I was not that strong.”

The writer tweets @FawadHazan

Dignity and a dime

Job opportunities for differently abled people are few and far between, but that may be changing ...

By Ahmed Yusuf

|

| PARKED IN: Fayaz Khan gives the thumbs-up to a colleague |

It takes 45 minutes for Fayaz Khan to hand-peddle all the way from Keamari to Sea View on his tricycle. He does not drive nor can he take a bus to work; Fayaz was hit by polio when he was just a year-and-a-half. So peddle he must, all 12 kilometres, because at Sea View lies happiness — a job that gives him dignity of labour, a decent dime to take home, and a sense of belonging.

“I am part of something big. I belong here, you know, I don’t feel out of place,” says Fayaz, who is now a watchman with Valet Solutions, a parking management company, and is deputed in the parking lot of Dolmen City Mall.

His job is simple: to keep an eye out for any miscreant or petty thief in the parking lot, and to blow his whistle if someone is there to steal or tamper with someone’s car. “It’s all about memory; I memorise faces quickly, and so I know who parked their car where. If someone else is messing with their car, I am the first one to know,” he explains.

While Fayaz’s tricycle had become his able support system for many years, transporting him around without anybody’s help and enabling him to explore on his own, it suddenly became an essential tool at his new job — on some days, Fayaz has to chase away miscreants and thieves; on other days, he must peddle fast to catch a thief red-handed. It’s a noon to midnight grind on some days, but Fayaz wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I completed my matriculation and became an apprentice with a tailor. But since electricity supply was always irregular in our area, tailoring work did not make ends meet for me. Afterwards, I set up a grocery store, and ran it for some seven years, but there was little fulfilment in that. A cousin then told me about this company, and here I am for the past six months,” he says.

Born in 1989, the wrinkles on his face and scars on his feet would have you believe that Fayaz is much older.

“I come to work because it gives me a sense of self; there is some satisfaction and some thrill too,” he says, explaining that most people who look at him peddling away his cart assume that he is some kind of beggar. He has been hearing such taunts since childhood but it is only now, at this job, that he has been able to use this perception to his benefit. “Sometimes, a miscreant or thief will think a beggar is passing by, when suddenly, they realise that I am actually a watch guard. Then they try and flee,” he smiles.

But beyond the miscreants and thieves, what is it that makes this job worthwhile?

“My colleagues’ attitudes,” he replies. “Never have I been made to feel different or teased about my disability. They are more likely to protect me than to hurt me, it wasn’t like this at the tailoring job or in my neighbourhood. I feel human.”

Much of this is because the other staff receives disability sensitisation training — how to behave around differently abled colleagues, how to ensure that they are not being mistreated, how to ensure that they never feel out of place.

“There is zero tolerance for harassment against the differently abled in our company,” says Omer Sheikh, chief executive officer of Valet Solutions. “We have a number of differently abled people, and we don’t tolerate any kind of misbehaviour towards any of them.”

Before starting Valet Solutions, Sheikh was in fact a banker for many years. When he was setting up his company, he wanted to help the differently abled in some shape or form. What he then wove into his business model was a number jobs that the differently abled could perform; most of his differently abled employees are deaf or dumb.

|

Another layer of the business was to ensure that there is theft and damage coverage in the event of any of his employees, including the differently abled ones, mess things up for the client. At present, there are 14 differently abled persons employed with Valet Solutions.

“We handle about 1,100 cars every day. In most situations, we don’t depute handicapped people to drive cars; they are there as service wardens, helping people carry their bags or trolleys. Most of these differently abled staff have been sourced from an organisation named Family Educational Services Foundation. Together, we try and create a difference to their lives,” says Sheikh.

It was while working with differently abled staff that Sheikh found some of his most-trusted staff.

“With such a high volume of cars being handled every day, at multiple locations in three cities, I needed someone to enter data of all receipts collected on a daily basis. I handed this job to Mohammed Arif, who had also joined us as a helper in the parking lot,” he narrates.

Arif is a 34-year-old deaf man, who now works part-time with the company. In the morning, he goes to work at an army base on Drigh Road as a data operator. By 3pm, he reaches his evening job with Sheikh, and stays at work till about 9pm.

“I used to work at a factory in Korangi,” Arif scribbles on a paper. “But people there were abusive and misbehaved often. They’d say I am deaf and can’t work, even though I would always do my job well They’d curse at me, blaming me for things that I didn’t do. It was in their body language.”

Now a father to two kids, a boy and a deaf girl, Arif works two jobs because both jobs have greater dignity of labour.

“I incurred heavy loans from my father since my daughter needed to be operated upon. My wife is deaf too, she loses her sight every now and then during the evenings. Doctors said that she needed to be taken abroad for treatment, but I don’t have enough money for that. We all do what we can just to survive,” he says.

“I admit that I cannot do everything for these people,” says Sheikh, “but what I wanted from the very beginning was to create a sustainable model for their employment, health and education. Even now, two days after many of them receive their salary, they’d come back asking for loans and advances. The company helps those in urgent need there and then, while we schedule when to help the others accordingly.”

In the case of 26-year-old Abid Arif, for example, employed in the company since the past one year, the company helped him find temporary residence on an urgent basis.

“Abid Arif turned up one day with a nail drilled into his hand by his father. He didn’t have enough money to give to his father for his drugs and alcohol, and the father beat him up, beat his wife up, and threatened to hurt their child too,” explains supervisor Mohammad Abid.

Arif’s story is one of a broken household. His mother passed away when he was 14, and ever since the father remarried, he was relegated to a non-entity in the house. Arif married out of choice, and his father didn’t approve of his partner, a deaf woman. Theirs has been a story of domestic abuse and suffering in silence.

|

| Service wardens greet customers upon their arrival to the shopping mall |

“I can breathe at work,” says Arif. “I feel suffocated at home. I need to leave behind the intense cribbing and fighting when I leave for work. When I am here, I put on my best smile and get to work.”

Smile and serve is also on the agenda for 27-year-old Shafqat Ali Khan. He proudly shows his t-shirt that reads: “The deaf can do anything except hear.”

Shafqat completed his undergraduate studies and applied to various jobs, but wherever he applied, the answer was rather discouraging and humiliating. He too tried his hand at the tailoring business, but things just didn’t work out.

“Shafqat now leads a six-member team at Ocean Mall, tasked with valet and support services. One day, the owner of the mall called in his staff and told them to learn better customer relationship techniques from Shafqat. He told them to learn how to serve with a smile from Shafqat, supposedly a man who is different from us. He got a cash reward too!”

Slowly but surely, the toil and triumphs of men like Shafqat are changing attitudes. Gone are the days when differently abled people could be brushed to the margins on the pretext of them being incapable of working. Along with this one, there are many other examples showing how running a profitable business is possible when you employ differently abled people. If the same model is extended into other public and private domains, meaningful change for the differently abled is not far away.

The writer tweets @ASYusuf

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, June 7th, 2015

On a mobile phone? Get the Dawn Mobile App: Apple Store | Google Play

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.