Rediscovering forgotten Indo-Persian works on Hindu-Muslim encounters

In the 1680s, a Safavid embassy en route to Southeast Asia stopped briefly in Madras, where several of the Persians attended a memorable party hosted by Franks (Europeans). The evening proved to be magical, if almost unimaginable, for Muhammad Rabi‘, a member of the Iranian diplomatic team.

Writing about the soiree, Muhammad Rabi‘ compared the unveiled white women at the gathering to huris, virgins of the Islamic paradise. He further developed the analogy by comparing their beauty with the “apparent heresy” of Indian Muslim ascetics conversing openly with Hindu Brahmins. The Safavid author speculated that even the most celebrated Muslim imams would renounce their faith in the face of such wonders and join these alternative forms of worship.

The forgotten Persian works on Indian traditions

This enchanting narrative rests strongly on the language of marvels, perhaps in part because the author – a foreign Shia Muslim – just landed in southern India and had little to no knowledge about the things he encountered there. His ignorance of European women’s fashion is understandable.

More striking, however, is his ignorance of the robust history of Muslim and Brahmin interactions, including the hundreds of Persian texts on Hindu knowledge that were circulating in South Asia in the late seventeenth century. Most people today are equally ignorant of this vast corpus of Indo-Persian materials.

Indo-Persian texts – works written in Persian within premodern India – are what one scholar has dubbed ‘homeless texts,’ falling between the cracks of Indian and Iranian nationalisms. In Iran, few people know or care about Persian literature produced elsewhere. In India, the focus often remains on premodern Sanskrit texts while Persian traditions are ignored.

Within this broader trend, Persian works on classical Indic traditions are especially neglected, in part, because of the now-rejected thesis that Muslim political and cultural hegemony in South Asia was the main reason for the decline of Hindu knowledge in the pre-colonial period. Still, few scholars and even fewer non-scholars are aware that between roughly 1200 and 1900 CE, Muslim and Hindu intellectuals in South Asia wrote literally hundreds of Persian texts on Indic traditions and sciences.

In 2009, we began Perso-Indica, an Analytical Survey of Persian Works on Indian Learned Traditions, a transnational research project that recovers how Hindu culture was represented and understood in Persian-medium texts composed between the 13th century CE and the 19th century CE.

Both Muslims and Hindus wrote these texts, which generally feature Sanskrit-based knowledge in a wide range of subjects, including astronomy, astrology, the epics, Ayurveda, popular stories, language, philosophy, and more. Altogether, this huge corpus of works easily constitutes one of the largest attempts to translate knowledge systems across linguistic boundaries in world history.

To analyse such a robust translation movement, we brought together dozens of leading specialists across the world who have participated in numerous conferences and are actively writing articles on individual texts. With nearly 150 articles are already available online, far more are still to come. The project’s articles will also ultimately be published in multiple volumes by Brill.

Perso-Indica is already radically changing our perspective on South Asian intellectual history, long viewed through a Sanskrit-centric lens, by introducing Persian as one of the main languages for the expression of Hindu culture in pre-20th century India.

The project also reverberates across Islamic Studies. It challenges the dominant Euro-centric perspective on the history of translation in the Muslim world, especially its narrow focus on Arabic-medium interactions with Greek and Latin textual cultures.

Perso-Indica uses digital humanities tools by producing metadata on each text that indicates its genre, author, era, location, and so forth. The website can then create charts and indexes using various parameters that enable researchers and casual users alike to discern trends that have, until now, gone unnoticed.

Neglect of manuscripts and monetary hurdles

Notwithstanding such progress and promise, Perso-Indica has encountered serious modern impediments to our ambitious aims. One major issue is that few scholars possess the linguistic and intellectual capacity required to work through many Indo-Persian texts. This is perhaps unsurprising given that our project emphasises texts that have been overlooked. The upshot is that we are cultivating scholarly skills while uncovering an under-investigated field.

In addition, we face obstacles while accessing specific texts. Many of the Persian texts included in the project are preserved only in manuscript form and have never been printed. But many South Asian collections of Persian manuscripts are closed off to researchers. Some lack even catalogues of their holdings, such as the important library of the Nawab of Murshidabad.

Even when we can locate texts, many Indo-Persian manuscripts have been left to moulder in neglected conditions. One of us was once shown a state museum library in India where Indo-Persian manuscripts were stacked, literally, floor-to-ceiling and visibly damaged. Many of us have had the painful experience of picking up an Indo-Persian manuscript only to have it begin to crumble in our hands.

Once, one of our researchers attempted to visit a private collection of books that belonged to a family of scholars in the northern Deccan. The family patriarch was willing to show the researcher the collection but required a week in order to dig up the texts that, facing space constraints, he had buried in plastic bags in his garden.

Many manuscript collections that ostensibly allow scholarly work, in fact, enforce anti-photography policies that prohibit it. Some libraries flat-out refuse to issue digital reproductions of manuscripts, which blocks work from being conducted by a team of international scholars situated across multiple continents, like the one working on Perso-Indica.

Some archives only allow photography of a limited number of pages or a certain percentage, 10% or 30%, of a given manuscript. Given that we are writing an analytical survey about full texts, we can hardly consider 10% of a given text and then break off. In theory, digital tools such as photography could create wider and freer access to primary sources and texts. However, recent attempts across India to digitise manuscript sources and then refuse to share those images are instead creating a potent means to control scholars’ access to primary sources.

Also read: Can Urdu and Hindi be one language?

Perso-Indica has also been hindered by the prohibitive costs that some libraries charge for digital reproductions of manuscripts. For instance, one of the earliest versions of the Blawhar wa Buzasf, a tale on the life of Buddha, exists in a sole copy in the Library of the Institute of Oriental Studies in Tbilisi, Georgia.

A humanities project like Perso-Indica cannot afford the library’s stated price for photographs of the manuscripts, more than one thousand USD. As a result, the Blawhar wa Buzasf will only be treated cursorily in our survey, and its sole copy in Tbilisi will likely continue to sit on a shelf, unknown and unread.

Perso-Indica aims to change peoples’ minds, about the depth and range of Hindu-Muslim encounters in premodern India, the contours of premodern Indian intellectual history, and the virtue of bringing together serious philology and digital humanities tools.

But to do so we must confront numerous modern problems, including attempts to control access to knowledge and a modern inability to imagine such a large-scale cross-cultural project in Indian history. Our hope is that, despite these obstacles, premodern Persian texts on Indic knowledge will change what we think we know about India’s complex past.

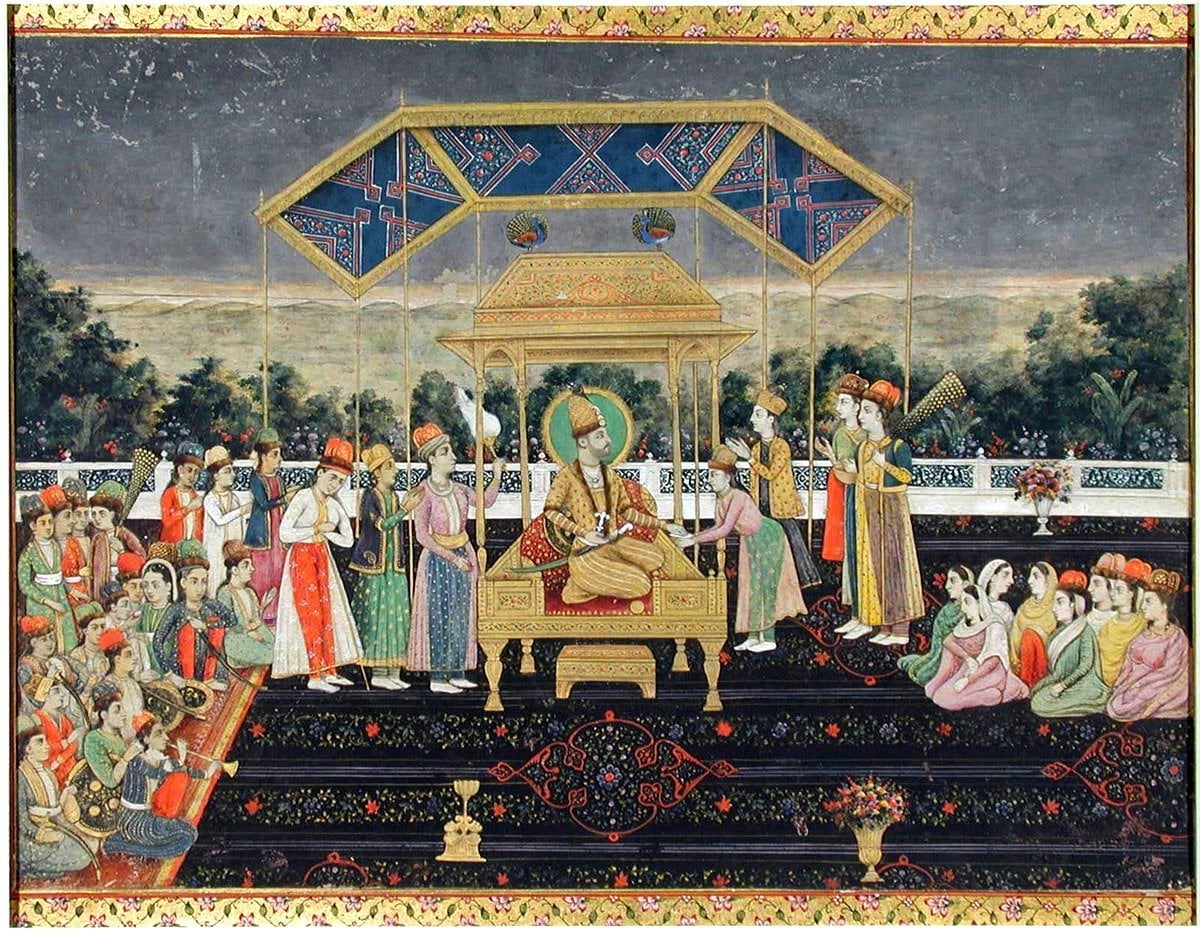

Header photo: Persian king Nader Shah on the Peacock Throne with members of the court.—Wikimedia Commons

This piece originally appeared on TheWire.in and has been reproduced with permission. The articles of Perso-Indica are available as an online publication and will be printed in chronological volumes by Brill.