FIGHTING FOR DEMOCRACY

The old woman sat on her haunches, native style, under a tree in the compound of Central Jail Karachi. I was sitting under the same tree, on a stone, waiting for the tiffin carrier to be returned to me. She was a small woman, poorly dressed, with teeth stained by paan and tobacco, her uncombed hair twisted into a tiny plait.

Just as in hospitals and clinics, patients in waiting rooms are curious about one another’s illnesses, the relatives of prisoners are also inquisitive. She had come to visit her son and had apparently lost another son to crime. After pleading before the ‘sahibs’ running the prison, she had managed to meet him across a grilled window.

Unaware of the procedure for getting permission to see her son, like most marginalised persons, she could only beg and plead. Rubbing the palms of her hands together, she said: “When I finally met him, he asked me, mother, have you brought roti salan for me? And when I answered no, I haven’t, he burst into sobs.” In despair she wailed, “How would I know that he wanted roti salan?” How could she have known, really, that the food served in prison was inedible?

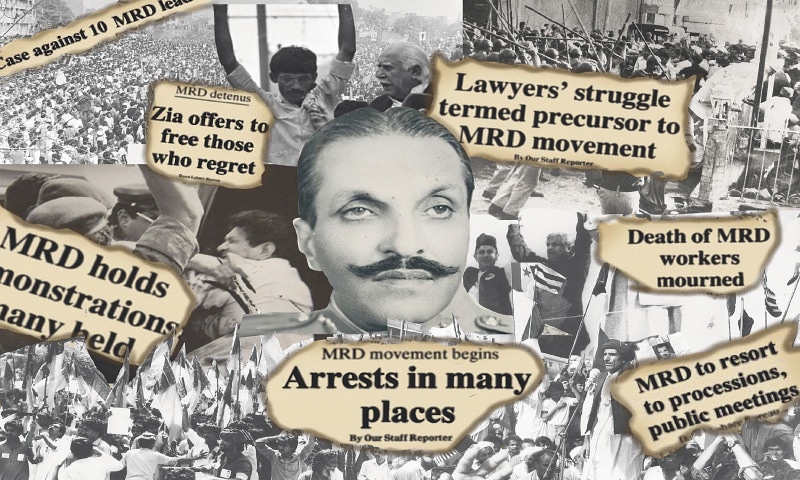

Her anguish broke my heart because I had gone to the prison to take roti salan for Fatehyab [husband and politician Fatehyab Ali Khan]. The Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD) had been launched.

Many politicians have taken credit for inspiring the movement after it became evident that [Gen] Ziaul Haq’s appetite for power was unrelenting. They met him when he called them, received his messengers, attended banquets he hosted for foreign visitors, and tried to ‘persuade’ him to hold elections. They could hardly have manoeuvred a showdown with the army under the brutal terms of martial law.

Ziaul Haq easily found collaborators among the parties which could not resist the lure of power. Members of the Muslim League, Jamaat-i-Islami (JI), Mufti Mahmood’s Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam (JUI) and Nasrullah Khan’s PDP [Pakistan Democratic Party] were sworn into his cabinet on August 23, 1978 and sent packing eight months later, on April 21, 1979.

Two prominent politicians, Sherbaz Khan Mazari and Asghar Khan, have written their memoirs and both used this ‘lull’ to go abroad on holiday. The former records several meetings with Ziaul Haq and participation in state banquets for the British prime minister James Callaghan, the Shah of Iran and president Sardar Daoud Khan of Afghanistan in 1978, and his surprise at finding other politicians such as Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi and Kausar Niazi also present.

He often received Lt Gen Fazle Haq in “his unofficial capacity as one of my oldest friends” [as Mazari puts it in his book A Journey to Disillusionment], who briefed him on political happenings and tried to convince him to join Ziaul Haq’s nominated cabinet, which he refused. However, on February 4, 1978, he attended Ziaul Haq’s special conference on national issues, as did others, which he described as “a grand and artful exercise.”

Asghar Khan, who had long aspired to become the prime minister and considered his Tehrik-i-Istiqlal as the real opposition — and it was, indeed, studded with many famous names in public life — also met Ziaul Haq, in the fantasy that he could be persuaded not to hold the local bodies’ elections or tinker with the Constitution.

Ziaul Haq, on the other hand, found one excuse after another for postponing the elections he had promised for October 1978, and told him that his own PNA [Pakistan National Alliance] colleagues had “begged” for this postponement [as Asghar Khan details in his book My Political Struggle]. Asghar Khan dined with Ziaul Haq, attended banquets for foreign dignitaries, and flew with him for the opening of the Thakot Bridge on the Karakoram Highway. He liaised with Ziaul Haq through lieutenant generals Faiz Ali Chishti and Fazle Haq.

It is difficult to assess what turn events would have taken if the leading politicians had refused to have any dealings with Ziaul Haq. Both Mazari and Asghar Khan had close friends in the army and hoped, no doubt, that their own parties would gain in a future political dispensation.

However, the Jamaat-i-Islami was firmly behind Ziaul Haq and so was Pir Pagaro; [Nawabzada] Nasrullah Khan had collaborated, and Wali Khan openly cooperated with Ziaul Haq and advised him not to hold elections. He and his wife had “a good understanding with Ziaul Haq” [as he describes it in My Political Struggle].

In his ‘real’ martial law, Ziaul Haq banned all political activity, imposed strict censorship and cruel punishments for even minor acts of a political nature. He had already terrorised the people with his regime of whipping, lashing and fear of amputations. The people of Pakistan had never been subjected to such systematic savagery.

In desperation, these politicians turned to one another and to [Zulfikar Ali] Bhutto’s widow to form a common front against martial law. It took many months and the process can be followed in the memoirs of Benazir Bhutto, Sherbaz Mazari and Asghar Khan. Fear of martial law and lack of courage had, as Asghar Khan said, prevented them from sinking their differences.

They were probably encouraged by the first lawyers’ movement, which started in August 1980, and led to the arrest of many lawyers who were tried by military courts. Asghar Khan even considered accepting an interim government in which Ziaul Haq could continue as the ‘constitutional president’ until elections were held.

According to Mazari, the first step towards the formation of the MRD was the initiative his National Democratic Party (NDP) took to contact other parties for a joint programme for the revival of democracy in August 1980. They proposed that the movement should have four basic demands: lifting of martial law, restoration of the 1973 Constitution in its original form, elections under this Constitution and greater provincial autonomy.

The PPP, which had given the first draft agreement through Pyar Ali Allana in December 1980, tried to hang on to Bhutto’s controversial constitutional amendments but had to give in. On February 5, 1981, Mazari received Nusrat Bhutto’s signature on the document and affixed his own and so, he writes [in A Journey to Disillusionment], “the MRD was formed.”

In the meeting on February 6, 1981, at Bhutto’s residence in 70 Clifton, Nusrat Bhutto requested that Fatehyab Ali Khan of the Mazdoor Kissan Party and Mairaj Mohammad Khan of Qaumi Mahaz-i-Azadi should be allowed to participate. They had “to sit outside all through the duration of the meeting while their case was argued” [according to Mazari’s A Journey to Disillusionment]. After the leaders affixed their signatures on MRD’s declaration, Mazari writes dismissively: “Even Mairaj Muhammad Khan and Fatehyab Ali were now invited to sign the document.”

The Central Jail Karachi was established in 1899. Many prominent leaders had been held there, the most famous being Mohammad Ali Jauhar of the Khilafat movement. Today, a ward is named after him in the prison. Bhutto was imprisoned there and, later, many MRD leaders, including Bhutto’s wife and daughter.

Having failed to motivate or bribe her party members to launch a popular movement against Ziaul Haq, Nusrat Bhutto turned to the men who had not lifted a finger to save her husband’s life. Indeed, they had scant respect for him and many of them had been victims of Bhutto’s oppression.

As we have seen, the choicest epithets are used for Bhutto in Mazari’s memoirs. Asghar Khan’s views about Bhutto were no less flattering. Apparently they did not doubt the fairness of the death sentence handed down to Bhutto by the Lahore High Court. Asghar Khan had met Ziaul Haq on March 12, 1979, three weeks before Bhutto was hanged, but did not plead for his life. He did, however, on one occasion, have the grace to attend Bhutto’s trial in the Supreme Court.

The senior politicians who signed the MRD declaration did not have much love lost for one another either. Mazari considered Nasrullah Khan as an expert in the intrigue of backroom politics with “an abundant store of political guile.” He [Nasrullah] had met Bhutto clandestinely during the PNA movement and always had “a personal agenda” [as Mazari writes in A Journey to Disillusionment].

Asghar Khan thought that, if left alone, Nasrullah Khan would have agreed to all Bhutto’s conditions for an agreement with the PNA. He had no real party, survived on political alliances and parleys, was not politically reliable, suffered from complexes and was a reactionary.

On the other hand, Mufti Mahmood of the JUI was not strongly opposed to Ziaul Haq, was flexible in his approach and would stay with any grouping so long as he was made the leader. Asghar Khan wrote [in My Political Struggle] that although Mazari was anti-Zia, his party would play to the tune of the military government.

Benazir Bhutto mentions [in her autobiography Daughter of the East] the feelers sent by the PNA leaders to her mother, who had become chairperson of the PPP. It was a difficult decision for Nusrat Bhutto to take. How could she forget Asghar Khan’s words at a PNA rally: “Shall I hang Bhutto from the Attock Bridge or from a Lahore lamp post?” The senior leaders of her own party had deserted her. “Today it is Jatoi,” she told her daughter, “tomorrow it will be somebody else.”

Although her rigid handling of the initial PPP movement against Ziaul Haq has been criticised, joining the MRD was a resolute act as well as a bid for survival, even if the PPP was just a “rabble” [as Raja Anwar writes in The Terrorist Prince]. The irony was not lost on Benazir, who watched the politicians drinking coffee out of her father’s china, sitting on his sofa, using his telephone. The PNA was riven by internal fissures and ‘betrayals’ by its leaders who were deeply suspicious of one another and talked only through emissaries.

Whatever these differences, the MRD charter was signed on 6 February 1981 on a four-point programme: lifting of martial law, restoration of the 1973 Constitution, holding of general elections, and release of all political prisoners.

There were nine signatories to the declaration: Nusrat Bhutto for the Pakistan Peoples Party, Sherbaz Mazari for the National Democratic Party, Mahmud Ali Kasuri for Tehrik-i-Istiqlal, Nasrullah Khan for Pakistan Democratic Party, Fatehyab Ali Khan for Pakistan Mazdoor Kissan Party, Fazlur Rahman for Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam, Mohammad Abdul Qayyum for Azad Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference, Mairaj Mohammad Khan for Qaumi Mahaz-i-Azadi and Khawaja Khairuddin for one faction of the Muslim League.

Following the hijacking of a PIA aircraft to Kabul on March 2, 1981, by Salamullah Tipu, the Al-Zulfikar agent, there was a severe crackdown on the MRD and thousands of people were arrested across the country.

However disdainful the old guard may have been about the leftist parties in the MRD, Fatehyab’s signature on its declaration brought the Pakistan Mazdoor Kissan Party (PMKP) (popularly known as MKP) into mainstream national politics for the first time.

A word about the party itself. It was founded on May 1, 1968 by Afzal Bangash, after he quit the National Awami Party. In 1970, Major Ishaq Mohammad of the Bhashani NAP faction in West Pakistan merged his group with the MKP. Its mobilisation focus was the peasantry, which had risen in armed revolt in the 1960s and 1970s in [the then] North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) against the private armies of landlords and the repression of successive governments in that province.

The confrontation in Mandani in July 1971 is regarded by the party as its glorious defining event. Although it led to the death of 20 peasants in a day-long pitched battle against 1,500 armed police, the peasants were victorious.

The party gradually enlarged its base among the peasants in Peshawar and Mardan districts, Malakand Agency, Swat and Dir and in parts of Kaghan and established links with peasants in southern and western Punjab. It participated in the movement against Ayub Khan in 1968-9.

Its first national congress was held in Shergarh in Mardan District, where 5,000 delegates assembled, in spite of the presence of armed security forces. It considered the PNA movement as reactionary and warned that it would lead to a military takeover.

But soon internal differences arose on strategy and the party split into three factions, led by Afzal Bangash, Sher Ali and Ishaq Mohammad. However, its continuity was best represented by Afzal Bangash’s group, which was generally recognised as the MKP.

The second or unity congress, also held at Mandani in July 1979, was a historic event in which over 5,000 delegates again participated from all over the country, in spite of martial law restrictions. Earlier, the PWP [Pakistan Workers Party], led by the veteran trade unionist Mirza Ibrahim, had merged with the MKP. By this merger, the MKP became a real peasants’ and workers’ party. The Mandani congress was attended by observers from numerous leftist parties and a message was also received from Benazir Bhutto.

At this congress, Afzal Bangash was elected as president, Fatehyab as vice president and Sardar Shaukat Ali as secretary general. Fatehyab had joined the PWP when it was established in 1972. Eventually, other leftist groups, such as the Mazdoor Majlis-i-Amal, Punjab Jamhoori Front and the Muttaheda Mazdoor Mahaz, merged with MKP in Punjab, further broadening its base.

The MKP had a genuine grassroots base among the peasantry, different from that of liberal parties whose following in NWFP consisted mostly of landlords. Its political programme called for a “people’s democratic system in Pakistan”, leading to socialism.

It viewed Pakistan as a federation of provinces which had come together in an equal and voluntary union, and in which the provinces would have complete autonomy. Its economic programme, with respect to landholdings and industry, was similar to that of other socialist parties. Different nationalities and ethnic groups would be given equal rights and fundamental rights would be universal, irrespective of nationality, religion, sect, caste, race, colour or gender.

Women had a special place in its programme, although the party’s base in NWFP was among very conservative peasantry. Women would have equal rights with men and no political or official position, employment or profession would be closed to them.

The MKP published extensively in Urdu and the regional languages. The popular struggles led by the party gave birth to a large volume of literature, song and music. No other party paid so much attention to political education as the MKP. Under its leadership, the peasants won many battles against the state machinery and landlords, against evictions, rent-racking and unpaid labour, and hundreds of its leaders, cadres and supporters laid down their lives in this struggle.

After the clampdown on the MRD, Fatehyab was arrested near Naudero on 4 April 1981, travelling with my brother Arif and our friend, Aftab Manghi, and brought to the Central Jail Karachi. He had gone underground in interior Sindh on March 9, 1981 and proceeded to Garhi Khuda Bakhsh for Bhutto’s death anniversary at a mammoth gathering.

The Central Jail Karachi was established in 1899. Many prominent leaders had been held there, the most famous being Mohammad Ali Jauhar of the Khilafat movement. Today, a ward is named after him in the prison. Bhutto was imprisoned there and, later, many MRD leaders, including Bhutto’s wife and daughter.

The social ostracism which I encountered after Fatehyab’s arrest was incredible, but not unexpected. My friends stopped contacting me and inviting me to their homes. Even if they were concerned about my welfare, it was not in their interest to be seen in my company. Their husbands had jobs, property and business interests to protect. They saw no reason to expose themselves to harassment for the sake of friendship. Gradually, but surely, they moved me out of their lives. Some even advised me to leave Fatehyab for good. The situation in my office also changed dramatically. My colleagues stopped recognising me.

Except for my private secretary, Rahmatullah Baig and my peon, Mannu, who were perturbed but caring, for the others I had ceased to exist. My colleague Amjad Ali Saqib, to whose friendship I owe a great deal in life, was cautious in the office but met me often at home. There was, I have heard, a barrage of anonymous and not-so-anonymous letters to the establishment in Islamabad, about my complicity in the movement against Ziaul Haq when, in truth, I was so busy trying to hold my family together that I was quite unaware of the outside world.

Matters came to a head on March 31, 1981, when I was sitting with the director, Iftikhar Ahmad Khan, in his office. He was blessed with a sense of humour and often discussed political issues with me. A few minutes later, there was a telephone call from Islamabad from Ijlal Haider Zaidi, the establishment secretary.

The expression on the director’s face changed and he asked me to leave the room. Shortly afterwards, he summoned me to say that Zaidi was furious and could no longer deal with the stream of complaints pouring into Islamabad against me. He asked me to apply for leave. I believe this was called ‘forced leave’. He insisted on six months’ leave but I did not agree to more than three months.

Some of my most vivid memories of those days relate to the time I spent at the prison gate, waiting for the tiffin carrier. In contrast to the attitude of my friends, colleagues and neighbours, the ordinary people were kind to me.

My removal from the official scene may have eased the tension that Zaidi claimed he suffered on my account. He hailed from Shahbad which was close to Panipat and had formed part of the constituency from which my father [Khwaja Sarwar Hasan] contested the elections in 1937. As establishment secretary, he was trusted by Ziaul Haq but he also held my father in great esteem.

Although making me inconspicuous may have played its part, I was probably not dismissed from service because of the regard which [politician and lawyer] A.K. Brohi, who was Ziaul Haq’s trusted adviser, had for me. Brohi was closer to Ziaul Haq than Zaidi. And, in any case, a faculty position in a training institution was hardly an important job.

In a sense, the ‘forced leave’ gave me respite, more time to spend with the children and look after Fatehyab from outside the prison. Our lives settled into a regular pattern. After the children went to school, I bought provisions and cooked for Fatehyab and some of his fellow prisoners. It was improper to send food for only one person, as all the political prisoners took their meals together.

I took the food to the prison gate and waited for the tiffin carrier from the previous day’s delivery to be returned to me. In the beginning, I prepared both lunch and dinner but, later, an agreement was reached among the prisoners’ families to divide the task.

Some of my most vivid memories of those days relate to the time I spent at the prison gate, waiting for the tiffin carrier. In contrast to the attitude of my friends, colleagues and neighbours, the ordinary people were kind to me. Shopkeepers and tradesmen in our neighbourhood enquired about Fatehyab, and the owners of Gharib Nawaz Hotel, where I purchased food when I was too tired to cook, always asked about his health, although they blasted their employees if the portions handed out to me were large.

The police guards at the prison were Sindhis who were all sympathetic to the PPP. Nusrat Bhutto was also detained in prison at that time and her staff drove with her food right up to the main gate. A really stylish constable oversaw the movement in and out of the compound, twirling his thick moustache and frequently blowing his whistle.

“Why,” I asked him one day, “do you let Nusrat Bhutto’s car drive straight to the main gate, while I have to walk all the way from the road?” “Because,” he answered, “her husband was a badshah [king], when your husband becomes a badshah, I will let in your car also.” I understood his simple logic.

My sons, Hasan and Asad, and I lived in a rented house in KDA Scheme One. The house opened on an unpaved dirt street, along which ran a deep stretch of water full of weeds which the odd angler frequented. In winter, Siberian cranes rested on the water. It was the darkest path in the entire neighbourhood. There were no street lights and people were afraid of entering it after dusk, but we had got used to its spookiness.

Often we had no domestic help because the police harassed our employees so much that they ran away. The chowkidar of the neighbouring house knew that Fatehyab was in prison and the children and I were all alone. He told me not to worry and that he would patrol the street a few times during the night. Often, as I lay awake, I could hear him thumping his heavy stick on the ground as he made his rounds outside. Whoever he was, I am grateful for his kindness.

In those times, so treacherous for my sons and me, my mother’s house was a haven of peace and tranquillity. She provided the stability in my children’s lives which I could scarcely muster in running around to look after Fatehyab’s welfare. She loved Fatehyab, his decency, cultivated manners, restraint and integrity, and she believed in his political mission. Never once did she suggest that he should give up his political engagements. She was the mainstay of our lives. Never failing in his affection and care, my brother Arif was a formidable source of strength and became a father figure to my sons.

My in-laws made some appearances, although they were so numerous that, if they had only taken turns, my life would have been easier. Other relatives were either scared or unable to express their concern, except my cousin Asima and her husband, Naqi Zamin Ali, who stood by me through it all. There was also the sympathy of some of my father’s friends, such as Ali Maqsood Hameedi, who were anxious about Fatehyab’s welfare.

Political prisoners were allowed visits from family members or friends once in two weeks, other prisoners could be visited once a week. But this facility was not automatic and permission had to be obtained from the home secretary each time.

During Fatehyab’s detentions and imprisonments, I dealt with a number of home secretaries, including Mazhar Rafi, Nazar Abbas Siddiqui and Ahmad Sadik. I was fortunate that they met me and were courteous to me. The relatives of less-known and poor prisoners were not so lucky; it was not easy to get past the bureaucratic barriers in Sindh secretariat, but they persisted. One person whose kindness touched me was the deputy home secretary, Ghulam Husain Soomro, who always granted permission ‘according to rules’ immediately and assured me that I was his ‘sweet sister’.

The first time the children and I met Fatehyab after he was arrested was in Bahadurabad police station and later in the prison on April 9, 1981. We went into the outer portion of the prison, or mari, with our small parcels of provisions and the cigarettes he could not do without.

A warden sat in the meeting room with us as Fatehyab came from the inner prison. Fatehyab entered with a smile on his face and addressing me said, “Now don’t unload yourself here.” We had to smile, there could be no complaints, no tears.

The writer is a scholar, former diplomat and top-level bureaucrat who retired from the civil service as Pakistan’s Cabinet Secretary in 2001. She is currently Chairman of The Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, President of the Board Governors of the Aurat Foundation, and Syndicate member and Selection Board member of the University of Karachi. Her book Pakistan In An Age Of Turbulence will be published by Pen & Sword Books

Excerpted by permission of the author

Published in Dawn, EOS, March 6th, 2022