Newborns: Unknown. Abandoned. Unwanted

|

| Photo by Muhammad Umar |

By Atika Rehman

Newborns dumped in trash piles have little chance of survival — and no record of death

In the dimmest of alleys in the City of Lights, something gory happens every day as a normalised reality: infants are dumped in a putrid heap of broken bottles, discarded sanitary items and household trash. The first caress against soft skin is that of a wild animal; a hungry feline or crazed dog pawing through a pile of trash for a meal. There is no anxious mother to answer the wretched child’s cries — is it cold? Wet? Hungry? Is it in pain? Soon, none of it matters. The pile of waste is set alight to become an unmarked smoky grave.

But talk to any first responders or a government agency about how many children perished in dingy alleyways, the answer is always the same.

“We are not sure; it could be hundreds or thousands,” says social worker Ramzan Chippa, whose eponymous centre provides shelter for abandoned children and homeless people.

“Ask Edhi, maybe they have numbers,” replied an official of the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef).

“Ask Edhi, people usually call them, not us,” responds an official of the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC).

“We don’t know how many babies are dumped this way,” admits Bilquis Edhi, the nationally respected matron, lovingly called ‘Mummy’, who has made her husband’s Edhi centre home to thousands of abandoned children.

The number of unnamed infants who die a brutal death are many, we are told, but nobody knows how many. News reports of children abandoned at trash sites around the city each year clamber into the hundreds, but there are no official records that can serve as an indictment. Unicef has no authentic statistics of such cases in the country, while the Edhi Centre and Chippa Welfare Association have no mechanism that regulates or records the exact figures of children recovered from trash sites, or given away for adoption. Both, however, provide estimates.

“Often, unwanted babies are thrown into the trash with their umbilical cord still attached,” says Bilquis Edhi “Sometimes midwives are paid by a couple to throw the child in the garbage for a sum of money.”

Chippa puts the number of such cases at “15 to 20 per month”. “We rarely find children alive from trash sites,” says Chippa. “Out of the scores recovered, at most four are found alive per year.”

According to Bilquis Edhi, the prematurely born infants die soon after they are thrown out. “They are thrown in the night and discovered wrapped in plastic bags or paper by garbage pickers the following morning. They are nearly dead,” she says, her steady voice betraying a hardening from years of beholding such horrors.

|

In a country of approximately 200 million people (we can’t be sure, no one counts the living either), the absence of the state from its obligation of social security and welfare allows civil society organisations such as Edhi and Chippa to plug the gap. These philanthropists work tirelessly, almost mechanically, to provide shelter, rescue services and food to scores of at-risk individuals.

And yet, organisations Edhi and Chippa are typically bound by their finite resources and outreach, their workers often occupied by the immediacy of the everyday. They cannot match the outreach of the state in coordinating and compiling numbers of all children who perished or who have been abandoned. No one is bothered with tabulating any numbers either, because it is not their job or their remit. Meanwhile, those who should be concerned with these statistics — the government — remains absent from the picture.

If it isn’t bad enough that there is no documentation of the dead, statistics for children who have run away from home in childhood are also vague. “Sometimes, people say 1.5 million children are runaways. At other times, these estimates go as high as 10 million. There is no confirmed statistic either way,” explains Lahore-based journalist Maryiam Pervaiz, who has worked extensively around the issue of street children.

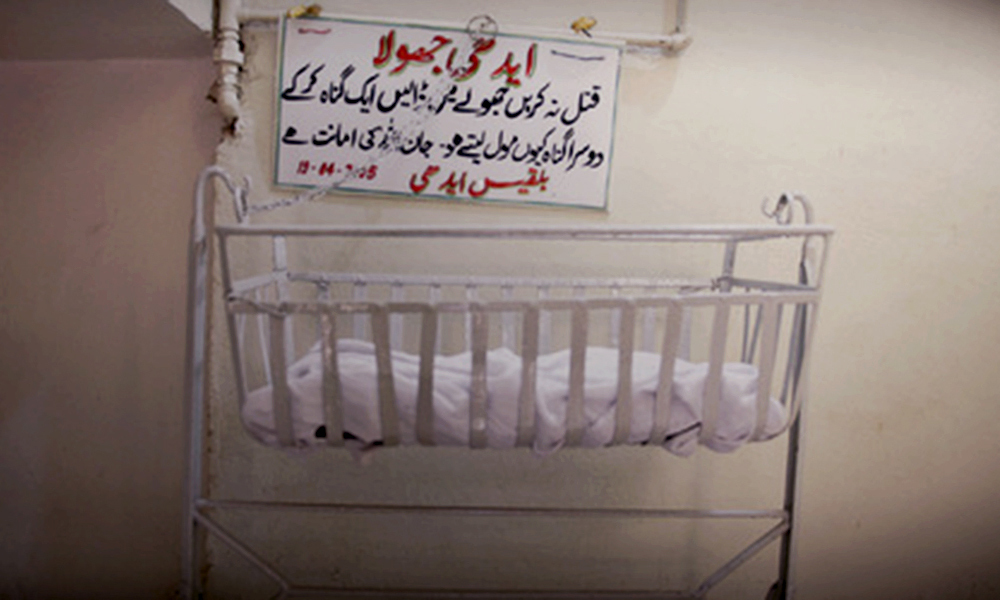

Despite the decades she has spent providing shelter to abandoned babies, Mrs Edhi is baffled when asked what compels couples to leave their flesh and blood at the mercy of wild animals. “Only God knows what their circumstances are,” she says. “The cradles at our Edhi centres clearly carry this message: ‘don’t throw your children in the trash, give them to us, leave them in this cradle’. After all, even a sickly child left in the Edhi cradle has a chance at survival. The ones thrown in the trash will most likely die.”

Dr Murad Moosa Khan, Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at AKU, says that while there is no study on these cases of abandonment, the speculation is that these children are born out of wedlock, are unwanted owing to pressure for a male child or are abandoned due to economic reasons.

“It is certainly a difficult act for any mother to do,” says Dr Khan. “But in some cases, the woman may be suffering from a psychological illness and may not have developed compassion or bonding with the child.”

Chippa’s account of the occurrence is harrowing. “These children are mauled by eagles, crows, dogs and cats… wild animals basically. They are found with eyes, ears or the nose missing – even if they survive, who will take these children [for adoption]? Parents who are adopting babies want healthy babies,” he says.

An ambulance driver working with the Chippa Welfare Association for 26 years narrates how some women told him about a child found in a manhole. “It was wrapped in a cloth and thrown in. I jumped in and picked up the shopper, I cleaned it with a towel. It was a boy. He was crying out, with its tiny arms open … if I was a few seconds late, the child would have died. It was floating in the shopper like mince meat. It was a beautiful child….What were those people [who discarded it]?… I had tears in my eyes. We have children of our own. It hurts so much [to see this]. My body starts to shiver,” he says. He adds that most children recovered from trash sites are girls.

Want of a son

Chippa says that among the cases of abandoned children, only a small number are born out of wedlock. “Nearly 98 per cent are [abandoned] because of poverty or the want of a son. Many couples have daughters but wish for a male child; when another girl is born, they feel compelled to get rid of it.”

At the Edhi Centre, Zohra Baji, who has been training mid-wives for nearly 35 years, says most of the abandoned infants recovered from trash sites are dead females. “This is our society,” she says. “I, too, was divorced by my husband because I could not give birth to a son after five daughters. My mother also had five daughters.”

The simple, elderly woman describes the sentiments of family members when a girl is born at the humble maternity ward at the Edhi Centre’s Meethadar unit. “When a daughter is born here, they [the family member] just leave,” she says, pointing to a stairway in the corner. They don’t check to see how the mother is doing; did she even eat? They don’t care. ‘Chalo’, they say, and are off in a huff.”

But if there is a son, there is fanfare. “The husband will bring halwa puri and press the wife’s feet. I tell them that daughters are a blessing of God but there are certain ethnicities that are overjoyed at the birth of a boy even if he is the tenth son,” she says.

Dr Murad Khan says the issue is not just limited to lower-income groups. “I have come across many patients who have given up a female child to a close family member, an infertile sister or another family member,” he says. “There are many such cases and the child given up is invariably female.”

|

He adds that foremost on the explanatory model is the pervasive idea that boys will carry the family name. “The idea is that the boy will carry the family name, look after the parents and be economically viable. He is ‘stronger’. There is a feeling that he will achieve more. The girl by default is perceived as a burden — someone who has to be educated or looked after and eventually will leave. They don’t see her as a continuity of family. This leads to the want for male and perpetuates the idea behind a patriarchal society.”

But without a mass, state-led awareness campaign about a child’s right to life or an emotional plea to the public that shows the dark fate of children abandoned at trash sites, there is little to persuade a mother against abandoning her unwanted infant in the garbage.

Due to an absence of state involvement in the provision or promotion of children’s welfare — with the job left largely to unregulated private charities — there is no knowing how many of these children are abandoned to meet a lonely death.

The writer is news editor at dawn.com and tweets @AtikaRehman

Abandoned

Unless rehabilitated, street children’s lives will remain at risk

By Irfan Aslam

|

In Lahore’s Liberty Market, nine-year-old Mujahid and eight-year-old Ali sell boiled eggs from evening until midnight. The sons of a menial labourer, they attend a private school during the day and earn a pittance at night, simply so they can take Rs200 home with them. Faizan, 10, sells children’s books on The Mall, where many families do their shopping from. He left school a year back, to help his elder brother earn a livelihood for his family. In the humdrum of Lahore’s markets, it is easy to lose the whereabouts of these children.

Were it 1999, they could have easily fallen prey to Lahore’s version of Jack the Ripper, a man named Javed Iqbal, who sodomised and murdered innumerable children, leaving behind no trace of their bodies as they were strangulated, cut into pieces and then dissolved in acid drums. His horrendous criminal activities continued until he was arrested the same year; most of his victims were runaway boys or street children, aged six to 16.

“There are three categories of street children; street-living children, street-working children and street children living with families,” explains Nazir Ahmed Ghazi of Grass Root Organisation for Human Development (GODH), which works on the rehabilitation of street children. “These children are vulnerable to many kinds of abuse, including drug and sex abuse — if not by anybody else, then certainly by other street children elder to them.”

Indeed, Iqbal’s accomplices included 17-year-old Sajid, 15-year-old Nadeem and 13-year-old Sabir — boys who had turned into abusers after being at the receiving end of abuse. Iqbal was convicted in 2001, and awarded a death sentence along with Sajid. After a few days of being convicted, Iqbal and Sajid were found dead in their cells inside Kot Lakhpat jail. Jail authorities termed the deaths as suicide, but Iqbal’s lawyers and media reports suggested it was murder.

|

Iqbal’s case should have shaken the conscience of the nation and the powers that be, but despite 13 years having elapsed since the incident, the on-ground situation regarding street children remains abysmal. According to some reports, there are about 1.5million children on the streets of the country, mostly in urban centres.

“In Lahore, the main centres of street-living children are Data Darbar, the railway station, its surrounding markets as well as Thokar Niaz Baig,” explains Ghazi. “A great number of street children are found in posh locality markets too, such as Defence. In fact, children found from Defence are often kept in bondage at the houses of the affluent.”

Despite the high numbers of street children in Lahore and how intractable the situation may seem, incremental efforts to redress the situation have also taken root.

|

| Photo by White Star |

Per the law, children are defined as “destitute” or “neglected” if they have “a parent or guardian who is unfit or [too] incapacitated to exercise control over the child.” The Bureau receives calls and complaints through its helpline, 1121. After rescuing any runaway or missing child, the CPWB takes them under its protection and asks a court to provide “clearance”. With these formalities out of the way, a child’s rehabilitation starts in earnest.

“In Lahore, we have more than 350 kids at a time; sometimes the figure can go beyond that,” says Rizwan Ahmed, the child protection officer at CPWB-Lahore. “The bureau has taken 27,000 children under its care since it started working in 2005 and facilitated many others. Our issue is more about what to do with these children after they turn into adults.”

Indeed, 17-year-old Mobeen Ali* is a young man on the cusp of adulthood. He has been with the Bureau for the last five years. “My father went missing, and I came here after the death of my mother. I have a grandmother and an uncle living in the city, but I would not want to live with them,” he says.

|

Ali is pursuing an FSc degree at a private college; he spends his mornings on campus and goes to an academy for further classes in the evening. He aspires to be an engineer but he does not know where he would go after he turns 18.

“Some children have been living with the Bureau since the past seven or even more years,” narrates Ahmed. “They are going to turn 18 soon, but there is no policy on how to integrate them into society after that point. There is a need to make a clear-cut policy in this regard.”

As it is, the weight of pending requests is already very high at the CPWB. “We get children mostly from police stations, hospitals and the trader’s community whenever they find someone in need of help. But poverty here is so crippling that even parents sometimes approach us to ask if they can leave their children with the Bureau. Sometimes, providing for the entire family becomes almost impossible for these parents.”

In the absence of strict laws for the protection of children, there is always a chance of authority being misused. In 2012, two cases were registered by the then CPWB- Faisalabad district officer against 11 employees of the Bureau for mistreating children and sexually abusing them.

The inquiries conducted by police and commissioner’s office termed the cases as motivated by personal vendetta but there are still an ongoing inquiry into that episode by the provincial home department. The CPWB’s internal inquiry had found some truth in allegations made from both sides.

|

There is a proposal to turn the CPWB, currently working under the Punjab Home Department, into a subservient part of the Social Welfare Department, but Rizwan Ahmed argues such a step would reduce the Bureau’s effectiveness. He says that to control the number of street children, the government should start a fund to help families keep children with them.

“There should be some fund like Benazir Income Support Fund to help the poor and destitute families raise children and stop them considering the children a burden or using them to increase income,” Ahmed suggests.

Meanwhile, Ghazi argues says that there should be legislation on compulsory schooling of children and punitive action for the parents who don’t send children to schools. “All the out-of-school children naturally turn into street children or become a part of bonded labour, living in conditions where they become vulnerable,” he says.

But there is consensus among all on one fact: saving these children from more Jawed Iqbals needs a lot more from society than is currently seen.

'Unwanted'

Abandoned by her birth parents, Lillian had to face another betrayal as well...

By Shameen Khan

|

| 67-year-old nurse Lillian Marjorie— Photo by Muhammad Umar |

In an alternate world, social worker Lillian Marjorie would still have been living with her “Mama,” finding solace in her lap, and safety in her shadow.

“I am 67 years old, but inside I am a child, I am lonely,” a pensive Lillian says.

Sitting comfortably on her mustard couch at her home in Karachi, she sinks deep into her thoughts. Dismayed by the images of the past that come to her mind, though, she snaps out of the moment instantly.

“I wonder where I came from and why my parents left me wrapped in a green swaddle, all by myself, near death. Why was I unwanted? I guess I’ll never know.”

Her story begins in 1947 when Mary Marian Sen, the director of nursing at the Lady Dufferin Hospital in Hyderabad was making her daily rounds. Sen stopped in her tracks upon overhearing the hospital guard talking about a newborn baby left just outside the premises.

It did not take Sen any time before she decided to give this child a name and make her a part of her family; this baby girl was named Lillian.

Together the mother and daughter spent two beautiful years, and soon after, the Sens welcomed another baby girl to their family; they named her Phyllis Merlon.

Lillian and Phyllis grew up in the same house and were raised as sisters. Mrs Sen made sure there was no difference in their upbringing. The sisters both had distinctive personalities; while Lillian was strong-headed and outspoken, Phyllis was an introvert and kept to herself.

“I was always very protective of Phyllis, to the extent that when her husband asked for her hand in marriage, it was me he had to please first,” chuckles Lillian.

In the 1960s, Mrs Sen decided to construct a house in the name of their daughters, and called upon the bishop to lead a prayer at the house blessing ceremony. During the service, the bishop stepped forward and said, “Mrs Sen is a kind woman, she has built this home for her daughters. One is her natural born while the other one is adopted.”

The bishop’s revelations stunned the girls, who were hearing about it the first time. Completely perplexed, they stared at their parents in disbelief, all the while as their mother’s expression changed from contentment to horror.

Wanting to know which one of them was adopted, the girls pushed their mother to tell the truth. But Mrs Sen kept the secret buried for weeks.

After much persuasion, it was disclosed that Lillian was the one who was adopted. Needless to say, the vivacious Lillian lost her spirit, and though she spent many nights crying, inside she knew that her mother, the woman who had raised her, loved her profoundly. Lillian was barely 18 at the time.

“My mama showed me the green floral swaddle she found me in, and the following days I could not help but wonder where I came from. I had countless questions on my mind; who are my parents? Why did they not want me?” recalls Lillian, wiping away her tears.

|

Her friends and family told her it was a bad idea to go in search of her biological parents, “What if they try to hurt you?” some of them said.

Gradually, Lillian recovered from having her world turned upside down for there was no wound in this world her mother could not heal.

In 1995, soon after Mr Sen departed from this world, Mrs Sen too passed away peacefully, and Lillian, according to her mother’s wishes, had her buried in a graveyard in Karachi. Her mother wrote a will and gave one copy each to the daughters.

But how things transpired from here onwards were to once again shake Lillian’s world. And this time there was no one she could run to.

“My mama didn’t get the will registered as she was unaware of the protocol,” explains Lillian. She says her mother was a simple woman and didn’t think about it much.

Upon Lillian’s return to their family home in Hyderabad, her brother-in-law greeted her at the door and said, “Why are you here? The woman who brought you into this family is now gone, so go live in the graveyard with her, we have nothing to do with you anymore.”

Lillian’s sister, brother-in-law and the rest of the family, all turned against her. The house too was taken from her. Even when Lillian took them to court, it didn’t help at all. In Pakistan, an adopted child has no legal right to inheritance regardless of which religion they belong to.

This episode altered Lillian’s life in ways she never imagined. She did not only lose her parents, but she also lost contact with her only sister. The family she once considered hers was now refusing to accept her.

In her childhood, Lillian recalls, Mrs Sen advised her on several occasions to hold back from being so giving with her sister. She said that when the time came her sister may not be able to reciprocate. After all those years, her mother’s words rang true.

Devastated, Lilian walked her own path and chose not to relive the pain of her past ever again. “I never got married because I didn’t have the courage to tell anyone where I came from and how I was abandoned, again,” she says, clearing her throat and gathering herself.

“I don’t want my children to ever turn around and question my identity. I don’t want them to question why I was unwanted.”

Though Lillian was alone, what she gained throughout these years was the affection of a woman who became her mother. She gave her a name and an identity and for that Lillian will be forever grateful.

Her mother’s love and kind words are what keep her going each day. The other main support systems in her life are her friends.

Lillian was baptized as a Christian, but in her heart she says she is a sufi who has given herself to others.

A nurse by profession, Lillian has dedicated her life to serving the less fortunate. Travelling across Sindh to remote villages, she has worked with numerous agencies and NGO’s providing necessitating nutrition to infants.

She has also served multitudes of people; both young and old, as a home care nurse in addition to establishing her own nursing centre.

“I only have one thing to say to the people who plan to adopt a child. If you make them yours once, don’t ever abandon them.”

As she walks in her garden, she lights a diya (lamp) for Ghaus-i-Pak, the sufi saint she reveres. Above the altar at her house, the four quls inscribed. She gets ready to say a prayer and whispers, “I will die a thousand deaths, just to have your arms around me, mama.”

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, December 14th, 2014