Swat: an unquiet calm

|

On September 12, 2014, the Pakistani army claimed the arrest of all 10 Taliban terrorists involved in the attempted assassination of teenage activist Malala Yousafzai and her friends, Kainat and Shazia. The arrests were announced some two years after the incident, which happened on October 9, 2012 while the girls were returning from school; all accused are said to hail from Malakand, with military spokesman Major General Asim Bajwa promising they would be tried under anti-terror laws.

Three days later, on September 15, Malik Zahir Shah, head of peace committee of Gul Jabba village of Kabal sub-division, was killed by unknown militants in broad daylight. He was murdered near a check post manned by security and police personnel.

Another two peace committee members — Muhammad Zaib Khan and Fareed Khan — were gunned down the same day in Bara Bandai area of Kabal sub-division, as they were heading home from a local bazaar. After their killings, locals say the army imposed a curfew in various villages of Kabal sub-division and started a search operation.

Between the military and the Taliban forces, the joust for power and control over Swat is ongoing — security remains in a state of flux despite five years having elapsed since the army first launched an operation in late 2007 to reclaim Swat.

In the beginning of 2007, Taliban militants led by Maulana Fazlullah, now central chief of the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) took control of the Swat district and waged a campaign of attacking schools, killing policemen, and beheading opponents.

An apparent crackdown on Fazlullah’s militia started in July 2007 by the paramilitary Frontier Constabulary (FC) force and the police on orders issued by then provincial government of the Muttahida Majlis-i-Amal (MMA) — an alliance of six religio-political parties — but it failed to establish the writ of the state.

|

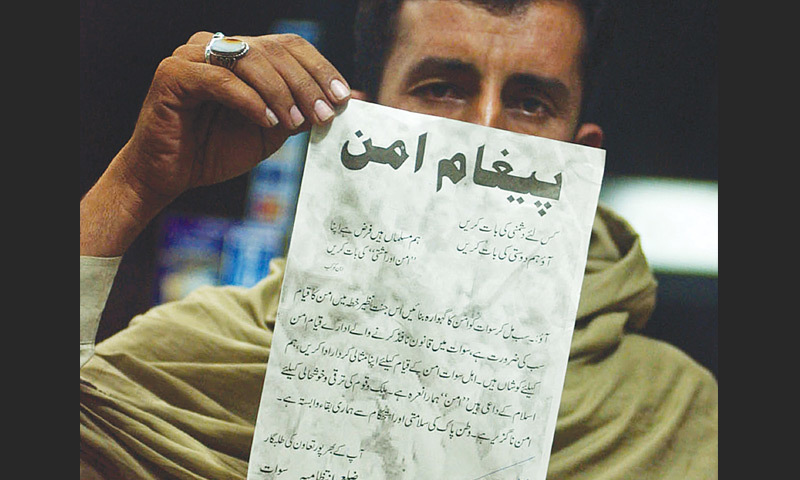

| October, 2007: A citizen shows a leaflet dropped by the government from helicopters in Imamdehri, a village of Swat valley, urging them to support security forces in tracking down militants.—AFP file photo |

As a result, Taliban militias became more powerful and more areas came under their complete control. Residents of Swat saw several small-level military operations and a peace deal between Fazlullah’s militia and the newly elected Awami National Party (ANP)-led provincial government in May 2008.

But even this pact could not deter Taliban militants from their subversive activities, including suicide attacks and attacks on state installations and security forces. Almost all organs of the state, including the police, the local administration, public schools, banks and courts retreated, closed down and disappeared.

However, in May 2009, Pakistani army carried out an operation against the Taliban militants which wrested control of the valley from their grasp, displacing around 1.7 million people in the process. But the remaining Taliban changed tactics and incidents of targeted killing of anti-Taliban figures and other subversive activities continue, whipping up fear among the local residents, especially those who supported the army in the operation.

Resurgence of Taliban activities

Omar Hayyat, an influential elder from the Takhta Band area of Mingora, was offering Isha prayers in the first row at a local mosque on July 23. As he prostrated, unknown militants climbed over the worshippers and shot Hayyat dead. The assailants escaped without any resistance.

“Jihadi groups such as Hizbul Mujahideen and Jaish-e-Mohammad which re-surfaced recently after 2007, are openly carrying out fund raising and recruitment campaigns in Swat.

In the last three years, a number of members of Village Defence Committees (VDCs) or peace committees — which are being organised at village-level in entire districts with the army’s support — have been targeted by unknown militants. Hayyat was one among them.

|

| November, 2007: A militant stands outside the local police station in Matta, with a signboard announcing that it the station is now under control of the local Taliban.—AFP file photo |

Feroz Shah, central leader of a committee formed at Kabal sub-division level, argues that political leaders and members of peace committees of Swat, who resisted the atrocities of Taliban militants and supported the army operation instead, are key targets of TTP militants. According to the police and media reports, at least 30 peace committee members have been gunned down in Swat in the last three years. In the same wave of targeted attacks, Taliban assailants attempted to kill Malala Yousafzai, the well-known teenage education activist, in 2012.

The killing of peace committee members is an ongoing process of retaliation, explains Sartaj Khan, a social researcher who has worked extensively on insurgencies in the Pakhtun and Baloch regions. “Most of these men have been instrumental in helping authorities arrest militants, destroy their houses, and even assisting in finding them in other places, such as Karachi. By killing the peace committee members, Taliban militants are trying to warn the others to keep distance from security forces.”

In recent days, militants also targeted army personnel. Two army soldiers on patrol were injured in an attack in Nazarabad area of Matta sub-division on August 15. After the attack, the army carried out a search operation in the area and detailed around 10 suspects. In another incident in May, an army vehicle was targeted in Malam Jabba.

Traders in Swat also complain that they have been receiving letters with the reference of Taliban leaders, text messages and phone calls asking them to pay extortion money. “We are getting phone calls with Afghanistan codes and Karachi numbers demanding we pay extortion money,” a traders’ leader in Matta said. While some local activists believe that local criminals are using the TTP name to extort money, a number of traders are silently paying up because of fear and very few traders have registered complaints in local police stations. In Ramazan, leaflets purporting to be from the TTP were distributed in Madyan bazaar, warning local women not to visit the market and bazaars.

“It would be good if the army allows the local administration and police to handle the security and administrative situation in Swat,” argues Yousafzai. Whether the local administration is up to that task is another question, however.

Great fatalities: Nepkikhel

Villages of Kabal sub-division situated to the north of Mingora (the main business hub of Swat) across the River Swat are inhabited by the sub-clan of the Yousafzais, the Nepkikhel.

The area was the birth-place of the Swati Taliban and Fazlullah is from one of its villages, named Mamdehrai. The majority of the assassinated Taliban militants and peace committee members both are from the region. “Only from the Nepkikhel region, with a population of around 500,000, more than 700 people who were associated with or sympathisers of Fazlullah, are still absconders,” Shah said.

|

| December, 2007: Pakistani troops capture Maulana Fazlullah’s sprawling Imam Dehri complex in Mingora.—AP file photo |

Background interviews with tribal elders and local residents suggest that security forces have detained a number of suspected militants from the region and that hundreds of them have died in military’s custody since 2009. Zama Swat, a Mingora-based news website, which regularly compiles such statistics, says that more than 300 detainees have died since 2009 and that the majority of them are from Nepkikhel.

The wives and children of the detained men hold regular protests in Kanju Bazaar, outside the army’s local headquarters and the residence of local MNA Murad Saeed.

“Security forces have arrested their relatives and now they are ‘missing’. We demand to show their whereabouts and present them in the courts,” said Jan Saba, a leader of the families of ‘missing persons’ from Nepkikhel region.

Swat connections with Afghanistan and Karachi

Although the government confidently claimed that militants were wiped out from the Swat valley in a successful military operation, local tribal elders and commentators say that while the lower militant cadre was arrested or killed, Fazlullah and his key lieutenants, along with a number of armed fighters, managed to flee into the Kunar and Nuristan provinces of Afghanistan during the operation. “The military operation has destroyed the command-and-control of Swati militants but it has not finished them,” asserts Khadim Hussain, a security analyst and author of The Militant Discourses.

Fazlullah, who was made new chief of the TTP after the killing of Hakeemullah Mehsud in a drone strike on November 1 in North Waziristan, declared that his organisation will continue to fight the Pakistani state until his version of Islamic law is implemented across the country. In a rare video message released on May 19, he directed suicide bombers to prepare to fight against the tanks and artillery of what he called ‘evil forces’.

As analyst Hussain describes it, the TTP has smaller cells in Kabal, Matta, Charbagh and Miadam areas of Swat, which, after the appointment of Fazlullah as TTP chief, have become active and are killing peace committee members with hit-and-run tactics.

Fazlullah and his fighters now carry out cross-border attacks in the bordering areas of Dir, Bajaur and Mohmand districts from Kunar and Nuristan provinces of Afghanistan. On June 4, seven security personnel were killed in Mamond area of Bajaur in a cross-border attack claimed by the TTP. In October last year, the TTP also issued a video of September 15 bombing that killed two senior Pakistani generals, Maj. Gen. Sanaullah Khan Niazi and Lieutenant Colonel Touseef, who were commanders in Swat, near the Pak-Afghan border in Dir district.

During the military operation, a number of Swati militants moved to Karachi, where they brought their fight to the streets of that city. Working in collaboration with Mehsud and Mohmand militants, Swati militants have killed a number of Swati pro-government elders travelling to Karachi for personal and business reasons, leaders of Awami National Party and now police personnel in the city.

Police officials believe that TTP Swat chapter in Karachi is led by Azizullah alias Baba Shamzai and Qari Shakir in Karachi. “Fazlullah, current chief of TTP, is personally ordering his Karachi group directly from Kunar province of Afghanistan to carry out subversive activities and kill policemen in the city following the killing of a number of militants in police encounters,” said Irfan Ali Baloch, a senior police official in Karachi.

Local residents in Swat are also concerned over re-emergence of Jihadi organisations, which mainly focus on Indian-administrated Kashmir, in the valley. “Jihadi groups such as Hizbul Mujahideen and Jaish-e-Mohammad, which re-surfaced recently after 2007, are openly carrying out fund raising and recruitment campaigns in Swat,” said Sardar Ahmed Yousafzai, a political analyst and president of Kabal Tehsil Bar Association in Swat. He said that supporters of Fazullah could join these Jihadi outfits and could deteriorate security situation in region again.

Withdrawal of troops and establishment of cantonments

During the Taliban reign, armed militants used to stop and search residents at checkpoints in different parts of Swat. But after the military operation, security forces now man such checkpoints. Residents say that the number of army checkpoints has been reduced now, although the army is also stationed on peaks of mountains surrounding the valley.

The Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI)-led Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government, after winning polls in May 2013 in the Swat valley and all of KP, worked towards a plan for the withdrawal of army from Swat. But according to a PTI parliamentarian elected from Swat the security situation, especially the assassinations of pro-government elders and the killing of Niazi, made pulling out the army impossible.

|

| November, 2011: Rebuilding carries apace at the Government Girls Degree College in Kabal, which was destroyed by Taliban militants.—Online file photo |

Now, the Pakistani military is constructing three cantonments in the Swat district to prevent attacks from the Taliban militants. Swat’s residents are divided over the presence of the army and the construction of cantonments in the valley. “After the withdrawal of the army, Taliban militants could again try to regroup in the area,” says Shah, adding that the army’s presence and construction of cantonment was necessary for maintaining peace in the valley.

However, some analysts and residents think differently and say that security check posts and search operations in different parts of Swat have frustrated the local community. “It would be good if the army allows the local administration and police to handle the security and administrative situation in Swat,” argues Yousafzai. Whether the local administration is up to that task is another question, however.

Local residents have their own conspiracy theories over the construction of cantonments in Swat. “It seems the emergence of Taliban in Swat and resultant military operation all was a drama just to acquire prime land in Swat for the construction of cantonment,” says Shah Hussain, a 60-year-old resident of Khwaza Khela. Villagers also complain that the prices they get from the government for their fertile land is far below the actual rate.

Civil society and environmental organisations have also expressed their concern over the construction of the cantonment in Swat. “Construction of three cantonments poses a serious challenge to the ecosystem and biodiversity of the entire region and violates international biodiversity and human rights declaration and conventions to which Pakistan is a signatory,” said an alliance of civil society organizations in Peshawar.

Implications

In June, the Pakistani army started a new operation in North Waziristan and analysts say that there are still a set of questions about the apparently incomplete job from the army’s first major operation against the Taliban militants in Swat valley.

Although terrorist activity in Swat is still less as compared to the rest of the country, analysts say that continuing attacks are belying the military’s claims of securing the area from militants. Military officials and experts say the resurgent Taliban will not be able to regain the hold it had over the valley from 2007 to 2009, but are likely to restrict their fight to hit-and-run tactics, an ideal guerrilla warfare approach in Swat’s rugged terrain. In the words of Yousafzai, “there is calm in the valley, not peace”.

The writer is a journalist and researcher. He tweets @zalmayzia

Harvesting deserts

Building cantonment areas on fertile land may irreversibly impact the traditional food basket of Swat, further weakening an already threatened ecosystem

Fazal Maula Zahid

The rich Gandhara heritage, the variegated history, and romantic folklore of the Swat valley is what once distinguished it from other tourist destinations. Located in the north of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, about 250km from Islamabad, Swat provided sustenance to its over two million-strong population through an economy centred around agriculture. But of late, authorities have decided to build three cantonments in the fertile, food producing lands of Kabal, Khwaza Khela and Barikot — a decision that threatens to irreversibly impact the traditional food basket of Swat, rendering many without subsistence or sustenance.

More than 75 per cent of the population, or 1.5 million people, is rural and directly dependent on farming for its survival. Landless farmers are also an important category. These “gujjars” traditionally keep animals such as buffaloes and cows for their livelihood. Women in Swat play an important, but often overlooked, role in agriculture in both crop and animal production. The land normally under cultivation is about 0.1 million hectares or roughly 0.25m acres and more clearly 2m kanals, out of which about 50 percent is rain-fed.

The 2010 floods devastated more than 40,000 acres of fertile land, around Swat valley bordering Kalam valley towards the Malakand agency. Considering a population of around two million and the productive land around two million kanals, the average land holding of under-cultivation land is less than one kanal per person. These farming systems require a high level of management practices and approach to technological advancement.

|

| Low-tech innovation at work |

The farming system in Swat is certainly a model for the rest of Pakistan, having a blend of both traditional and non-traditional cropping patterns, in fruits, cereals, vegetables, non-timber forest products (NTFP), medicinal herbs, honey, silk and nursery production and so on. It emerged, in a short span of time, as a hub of a variety of fruit growing orchards, off season vegetables and cereal crops with an excellent production, value addition and supply chains.

Given that traditional Swat farmers receive little or no water and have almost no access to agricultural inputs such as fertiliser and pesticide, the farmers are praiseworthy for their indigenous enterprise and for sustaining their families through just small tracts of land.

The farmers in Swat not only grow crops and vegetables but they also rear and keep livestock and poultry. The main crops of the valley are wheat, maize, onion and rice, while livestock includes cows, buffaloes, sheep, goats and domestic poultry birds. Swati rice commonly known as ‘Begamai’ is renowned for its quality, with its lore travelling all the way to Karachi as well. Because of its quality and flavour, the maize grain cultivated in Swat has an edge over its competitors in the Pakistani market.

Amongst horticultural crops, the valley is famous for apple, persimmon, peach, pear, apricot, plum and citrus etc. During the harvest season, market players, industrialists, transporters and multinational firms all establish their effective networks in the valley. Skilled labourers from southern districts and even from Punjab arrive in Swat to work in the fruit-growing areas of the valley; it employs 56 percent of the local labour force throughout the year.

Swat is also a centre of soybean cultivation. This is a multi-utility crop having many positive considerations as compared to other competing crops. Seeds of soybean meant for use in other parts of the country are also produced in upper Swat.

Honey from Swat is perhaps among the most famous products exported by the valley, often distinguished by both price and demand. Delegations of farmers from across the country used to visit Swat and would learn from the agriculture system here. Similarly, many experts from around the globe also worked here and appreciated the role of the local farmers in the development of agriculture.

“People of Swat are an extremely good looking people, and of a much more demure nature than most Pakhtuns, who are known to be boisterous”, writes an academic Fasi Zaka on February 12, 2009 who visited the Swat valley in connection with a study in the area during the peaceful times before the conflict.

The writer says, “Several years after the completion of my education I went to Swat on a research project for the first and last time looking into the value chain of apple growers for the export market. I met many farmers, intelligent family men who were seeing hard times in agriculture but were optimistic about the future. Despite their hardships, they conformed to the gentleman farmer mould. If you had asked me at the time what would be the main concerns of Swat several years into the future, I would have said it was the decimation of the population of bees due to pollution that was affecting the pollination of fruit-bearing trees.”

The region that is spread in 100 aeronautical miles is almost, a summary of the universe. It is the food reservoir, not only for 2m of its populace, but for diverse kinds of plants, wildlife, birds, bees and micro organisms. This rare and precious natural resource is now under severe threat, owing to a rapid and highly unsustainable development model. Fertile green land is being converted into roads, homes, townships schemes and so on.

The forests and mountains of Swat act as water reservoirs for districts in the south. The irrigation of large parts of land depends on the Swat River, which is replenished with yearly snowfall on the hilltops. The hilltop snow in turn depends on the dense forests and the biodiversity of this enchanting snow valley. Both of these critical resources have been declining in recent years.

The above facts reveal that such precious but limited resources require proper land-use planning. Climate change threatens the fertility and food production of the entire region owing to changing crop production patterns. Pakistan, experts argue vociferously, is destined for desertification by both man-made and climatic patterns by 2025. If traditional “green growth” is replaced by “brown growth,” Pakistan’s slide into a more fragile ecosystem will be much quicker. Thus, the construction of large cantonments must take into account the effects on the ecosystem, or all that will be left to defend is an infertile desert.

The writer is an agriculture expert and has also served as the secretary of the Rotary Club Swat. email: fmzahidswat@gmail.com

The nine-year wait for a jail

|

| A view of debris piled up at Saidu Sharif Jail in Swat - Photo by author |

Swat lost its district prison to the 2005 earthquake, forcing common criminals to share space and facilities with hardened militants in Timergara and Buner.

Irfan Haider

**Almost every three minutes, 52-year-old Hajra Bibi knocks on the main gate of Timergara’s district jail, situated on the main road along the Panjkora River in the Lower Dir district of Malakand Division.

The clock has just struck three in the afternoon and Hajra has just reached Timergara after a 80-kilometre long journey from Tehsil Kabal, District Swat. Locked up inside is her 28-year-old son, Jamal Khan* — apprehended and tried in Swat. Hajra makes this tiring trip all the way from Swat to meet Jamal once every month, but sometimes, she must make the journey back without being able to see him. Today is one such day.**

“I have been requesting the sentry to allow me inside, but he is refusing since inmates’ family members can only meet them until 1pm,” says a distraught Hajra. “My son Jamal was a labourer. Security forces arrested him during the Swat operation back in 2009, on charges of having some alleged links with the Taliban. It is difficult for me to hire a good lawyer to secure his release because I don’t have the money to do so.”

Unlike Hajra Bibi, 55-year-old Nazir Khan, a resident of Matta area in District Swat, walks out of the prison a tad more content. He was successful in meeting with his 24-year-old daughter, Shabnam Bibi, who is on trial for allegedly murdering her husband four years ago. “I met my daughter after 20 days; I woke up early morning to reach Timergara, because the management is very strict about their 1pm deadline,” he says.

Both Jamal and Shabnam were booked back in Swat, their hearings too are held back in their district, but they are detained in Timergara’s district jail since there is no prison left in District Swat after the 2005 earthquake. But the Timergara jail also serves another purpose: it is where the army sends the prisoners of the operation against militancy.

|

| A view of the dilapidated Saidu Sharif Jail in Swat |

Per national security practices and protocols followed today, nabbed high-profile militants are first taken to army-run detention facilities, where investigations are held as is some re-education to undo what officials described as “militant brainwashing”. Prisoners are then either let go or shifted to the district prison in Timergara or to Dagar jail in Buner district of Malakand division. “Dozens of terrorists are present in the prisons of Timergara and Dagar who were captured by the security forces since the start of the militants’ activities in Swat in 2007,” admits Malik Qasim Khan Khattak, advisor to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa chief minister on prisons.

Even today, the military continues to send prisoners to Timergara. If his mother’s belief is well-placed, Jamal might well be innocent but he is nevertheless imprisoned along with “dozens of terrorists” captured by the military since 2007.

War on ruins

Timergara’s district jail assumed greater significance after the earthquake in 2005: the prison in Saidu Sharif (district headquarters of Swat) became unusable as a detention centre after the quake, and prisoners from Swat were shifted to Timergara. “It is the largest and most secure facility that is currently operational,” says a jail official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Even today, the military continues to send prisoners to Timergara. If his mother’s belief is well-placed, Jamal might well be innocent but he is nevertheless imprisoned along with “dozens of terrorists” captured by the military since 2007.

In a sad twist of fate, the Saidu Sharif prison was in fact renovated and its capacity increased from 200 prisoners to 700 back in 2005. “The jail was constructed in 1950, during the era of the first wali of Swat, Miangul Golshahzada Abdul-Wadud Badshah Sahib. In 1971, its capacity was 200 given the population at the time; its expansion was completed as recently as 2005 but it was also ruined the same year,” recounts Munir.

Nine years on, as conflict rages on in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the Saidu Sharif jail still remains in a state of disrepair.

|

| The abandoned lockups of the Saidu Sharif prison. — Photo by author |

“The Communication and Works (C&W) Department of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa declared the Saidu Sharif prison inoperable after the earthquake,” explains Akhter Munir, the superintendent of Saidu Sharif Jail. “The provincial Awami National Party (ANP) government then directed the authorities concerned to completely vacate the prison and move the prisoners to Timergara so that repairs could be arranged in Saidu Sharif. Funds for the reconstruction of jail were allocated in 2007.”

Before the renovation plans could materialise, the army moved in on Swat to clear the area of militants.

“Security forces took over the Saidu Sharif prison for the operations, and many of their personnel resided inside jail premises. The prison therefore became a target of many attacks, as militants would target any and all buildings they thought were being used by the security forces,” narrates Munir.

With the entire jails’ burden now transferred to Timergara and Dagar, much overcrowding began to take place in the two operational prisons. Mian Mohammad Anwar Khan, the superintendent of Timergara jail, says that the prison’s capacity is 240 but the number of prisoners totals around 550, including 22 females.

“The prisoners mostly belong to Swat district; it is difficult for the police to provide basic facilities to everyone in jail due to the lack of resources and the additional burden of the prisoners,” claims Mian Mohammad Anwar.

Likewise in Buner, the jail’s capacity is around 250 but around 300 prisoners are locked up. “Most of our prisoners belong to the Swat and Shangla districts of Malakand Division. But it is now very difficult for the jail administration to manage local Buner prisoners due to the shortage of space in our jail,” contends Murad Khan, the deputy superintendent of Dagar Jail.

Transporting trouble

“Court hearings are all held in Swat because the courts are located in Mingora, the divisional headquarters of Malakand Division,” complains Nazir, based on his troubles of reaching Timergara. “It is challenging for me to travel due to my old age while it is also difficult for me to spend almost Rs500 to 1,000 for each visit to my daughter’s prison.”

|

| A view of the entrance of the courts in Swat |

But as the district police officer (DPO) of Swat, Sher Akbar Khan, explains, the torment is not of common citizens alone. “The sufferings of the police department have also increased because it very challenging for the police to move prison vans on a daily basis from one district to another district for the hearing of cases,” he argues.

At least six prison buses, along with additional police vans for prisoners’ protection, are employed every time prisoners have to be shifted from the jail to the courts. “There is always a threat for the police authorities; any terrorist group can attack the buses to secure the release of their associates,” explains DPO Sher Akbar. “This happens especially during the winters, when the days are short, and it becomes a challenge for the police to return the prisoners to their jails before sunset.”

Much expense is therefore incurred on shifting prisoners to and fro. “I don’t have an exact idea but the police department is spending around one million per month for the transportation of the prisoners while the police are also providing separate transport to women prisoners,” says the DPO.

“It is unfortunate that the expenses of the police department have increased due to increased fuel costs, maintenance of buses being used, and the added human resource to protect police vans from any attacks by terrorist groups active in FATA,” Sher Akbar laments.

Tardy is marked absent

Despite the expense incurred on transporting prisoners from one district to another, it isn’t always the case that they would have a hearing before a judge. If they are tardy in reaching the courts, hearings are often cancelled.

“It is very common in courts that judges cancel the hearing of the cases due to the unavailability of the prisoners in the court on time. The police are often delayed due to the long distances they have to travel from Lower Dir and Buner,” explains Mohammad Zahir Khan, president of the district bar association in Swat.

“How can it be possible to continue proceedings of a trial regularly if a prisoner is not present in court by 3pm?” he asks rhetorically. “Sometimes, prisoners reach after court hours, at other times it is necessary to get the signatures of the superintendent on a bail application to guarantee bail of any accused in criminal cases. It is difficult for lawyers to use extra time and additional money to visit jails in other districts to meet with their clients and discuss their cases.”

Zahir says that the bar association also staged a protest against the lack of jail facilities in Swat, while lawyers’ representatives also requested local parliamentarians to allocate funds for the reconstruction of the jail, but there has been no progress as yet.

Double sentence

Thirty-five-year-old Zeenat Bibi*, a resident of Saidu Sharif, waits for her bus to Buner at the Mingora bus stop along with her 12-year-old son. She is going to visit her husband, who is behind bars in the Dagar prison since April 2012 on charges of corruption.

“It is impossible for me to visit the jail alone to meet my husband due to our family norms; my husband told me to visit the jail only with my son, who studies in class 6 in a local government school in Saidu Sharif,” explains Zeenat said.

“I know that I will return from Buner by evening and not earlier, because the buses take almost six to seven hours from Swat to Buner and then back from Buner to Swat because of the damaged highway. I told my son to take leave from school, as it was the only option for him to go with me to meet his father,” she adds.

In Mingora city in district Swat, 42-year-old Ahmed Khan* is also preparing to reach the Dagar jail to meet with his younger brother, incarcerated for the past year due to charges of murdering a relative over a land dispute. He complains that each leg of the 90-kilometre journey costs Rs360, and the bus takes almost six hours from Swat to Buner and then back to Swat.

“My mother wants to meet my brother in jail but it is difficult for her to travel in a local bus because she is a heart patient and has blood pressure issues due to her age,” says Ahmed. “Although, my mother did meet my younger brother a few times during the hearing of his case in Swat, it will be easier for inmates’ families to meet them if the government takes some steps to reconstruct the jail in Swat.”

Then there is the family of 55-year-old Ziarat Gul*, a resident of Swat who is imprisoned in Dagar. He meets his family usually in court premises, since it is very difficult for his whole family to travel all the way to Buner. “My brother likes to meet with me in jail, but sometimes, he has to stay the night in Buner due to the long journey back to Swat,” says Gul.

The incumbent provincial government is not interested in taking immediate measures to rehabilitate the existing jail, claims an official of the KP C&W Department, speaking on condition of anonymity. He maintains that the government has instead decided to construct a central jail in Swat.

When contacted, Malik Qasim Khan Khattak, advisor to the KP chief minister on prisons, and Salim Rehman, the local member of the National Assembly from Swat, told Dawn that the KP government is aware of the sufferings of prisoners, their families, police personnel and even lawyers.

“The provincial government has allocated funds in the budget for the construction of a jail in Swat but it is difficult for me to tell you the exact amount allocated,” says Khattak said. This was echoed by Rehman, who adds that it is necessary to construct a jail in Swat so as to counter any possible terrorist attacks.

Meanwhile, Hajra Bibi returns home from Timergara with only the hope that one day, her son will be released from jail. She wants to fulfil her dream of fixing his marriage and seeing him wed in the near future.

*Names changed to protect privacy and anonymity

Irfan Haider is a Dawn.com correspondent in Islamabad.

Connect on Twitter at @IrfanHaiderr or email him at mihader321@gmail.com

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, September 21st, 2014