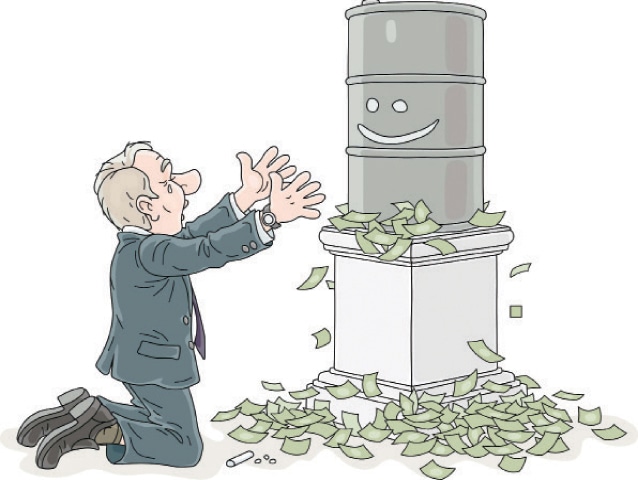

A debtor that defaults faces consequences. But so do other companies that operate in the same industry — especially if the defaulter in question is Hascol Petroleum.

The oil marketing company defaulted on its loans of roughly Rs54 billion last year. It sent a jolt of panic through the banking system. Lenders became wary of the energy sector, assuming that all companies were prone to default.

Banks immediately froze — if not reduced — their credit lines to oil companies. And the result has been catastrophic for every player, barring government-backed entities in the oil value chain.

Take the hypothetical example of an oil marketing company that had a credit line of, say, Rs50bn back when the oil price was $60 a barrel and the exchange rate was Rs100 a dollar. Now the oil price has doubled to $120 a barrel while the dollar rate has climbed to Rs200. Yet the credit line is frozen at the previous level, effectively sucking the liquidity out of the oil value chain. Most refineries currently have idle capacities while their CFOs run from pillar to post to arrange financing for the import of crude oil.

Liquidity shortages force refineries to reduce throughput as banks look the other way

“We need working capital lines of at least Rs100bn if we have to produce about 75,000 barrels per day (bpd),” said Zafar Shahab, CFO of Cnergyico PK Ltd, the largest of Pakistan’s five refineries with a production capacity of 155,000bpd.

Currently, it’s refining only 55,000bpd mainly because banks have capped its credit lines to a total of just Rs43.5bn.

In contrast, the government-backed Pak Arab Refinery and PSO-owned Pakistan Refinery have working capital facilities of Rs144.5bn (120,000bpd capacity) and Rs51.2bn (50,000bpd capacity), respectively.

Other private-sector refineries face equally constrained working capital lines. With a 70,000bpd capacity, National Refinery’s credit lines are capped at Rs105.8bn while those of Attock Refinery (53,000bpd capacity) have a ceiling of just Rs3bn.

Sources in the banking industry say even the largest of banks have turned their backs on the oil sector. “Banks wonder why they should bother arranging $75 million for opening just one letter of credit (LC) when they’ve already learned their lesson the hard way,” said a banker requesting anonymity.

Law enforcement agencies rounded up over a dozen officials from a government-owned bank in the aftermath of the Hascol default. Teams from the regulator have visited commercial banks to look into their loans to the oil industry.

It didn’t help matters that the central bank governor reportedly accused bank treasuries of “currency speculation” leading to a hike in the interbank exchange rate late last year. Banks don’t like when they get thrust into the limelight for arranging credit for oil imports given the sheer size of a typical transaction.

“The rupee depreciates the day any oil payment is due. Oil trade is about a quarter of the total market. The depreciation is automatic,” the banker said.

This problem has now spilled over to the international banks as well. They too find it risky to “confirm” LCs opened by their Pakistani counterparts. Oil suppliers require international banks to back up the LCs from Pakistani lenders to ensure protection against payment failure.

“Global banks have capped their exposure to our oil business despite the overall doubling of prices in the international market. Every private-sector company is struggling,” says Mr Shahab.

So what’s the net impact of the oil industry’s liquidity crunch in layman’s terms? For starters, the throughput of refineries has gone down because they don’t have access to working capital to arrange crude oil imports.

Yet the “product” imports have gone up given the rising demand amidst the availability of subsidised fuel at petrol pumps.

“If the banks extend credit lines for crude oil, the country will save more than $700m a year by cutting down its imports of finished petroleum products,” he said.

Finished petroleum products are typically more expensive than crude oil. But the Russian-Ukraine war has resulted in the unprecedented widening of this delta.

The price difference over crude, including premium, in the case of diesel is over $51 per barrel. It’s more than $38 per unit for petrol.

“If the refineries operate at their full capacity, the country will save more than $200m a month or $2.5bn a year in foreign exchange,” he said.

Published in Dawn, The Business and Finance Weekly, June 6th, 2022

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.