WRITING about writers is not easy as it requires some peculiar qualities: a love of literature and arts, vivid imagination, tender soul, fascination for the printed word and — above all — empathy with those who write.

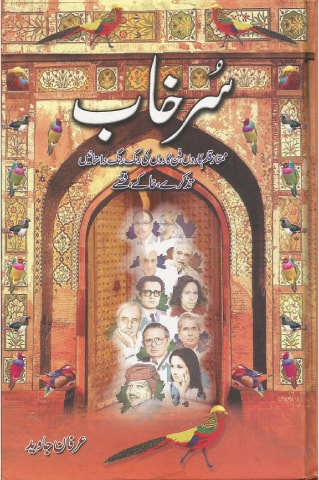

Irfan Javed has been endowed with these qualities in abundance as is evident from his book Surkhaab. Narrating the lives, traits and quirks of some writers, poets and painters, he has lovingly recalled some fond memories of the time he spent with these renowned creative geniuses. The book also remembers the ones he could not meet, like Sa’adat Hasan Manto, but narrates their life in a passionate manner, bringing them to life with vivid imagery.

With a touch of imaginative thoughts and a generous sprinkling of romanticised notions, Irfan Javed has weaved together some tales, events and impressions about writers, poets and painters and these pieces are dripping with colours. Aptly named Surkhaab — alluding to something drenched in colourful splendour — and subtitled Tazkire, Khake, Qisse (remembrance, pen sketches, tales), the book, true to its name, weaves together some colourful pieces that make absorbing reads.

Published by Lahore’s Sang-i-Meel Publications, the book is a collection of pieces that can either be called biographies or critical evaluation or even pen sketches dotted with anecdotes, giving it a touch of memoir-like descriptive writing that defies all definitions. However you describe them, these pieces are indeed a good read as they are peppered with strange events, literary references, wisecracks, interesting reminiscences, anecdotes, eccentricities, foibles and idiosyncrasies. The personalities remembered are: Khalid Hasan, Parveen Shakir, Ustaad Daaman, Sa’adat Hasan Manto, Joan Elia, Mansha Yaad, Tasadduq Suhail, Gulzar, Amjad Islam Amjad, Muhammad Ilyas, Ayoob Khawar and Iftikhar Bukhari.

Before the present volume, Irfan Javed has published Darvaaze, a collection of pieces that fall in the same, indescribable genre which is yet to be named. This is not to say that what Irfan Javed has penned is not attractive or appealing, but it is indeed a kind of cocktail made with the ingredients used in different genres. What has made these pieces interesting yet tangential at times is the writer’s tendency to drift away and sharing his memories or views that are apparently irrelevant, however interesting. Though they are not totally irrelevant and add to the impression the writer wants to create. But such diverging points sometimes either sound like writer’s personal memoir having little relevance to the subject or they seem pedantic. The excessive details, however interesting, make the book drag at times.

But one has to admit that Irfan Javed’s hugely vast reading has made him so erudite that allusions to English literature, Urdu poetry and philosophy make the book a companion that can be very soothing for tender and romantic souls.

While it is all authentic, there are some minor lapses that need some correction. For instance, while referring to Jagan Nath Azad in the piece on Ustaad Daaman Irfan Javed says that Jagan Nath Azad had written Pakistan’s first national anthem (page 51). This is absolutely incorrect and this writer had written a piece on the issue (Dawn, July 4, 2011) to repel this misconception with reference to Aqeel Abbas Jafri’s book. Pakistan’s first national anthem was written by Hafeez Jallandhri and Jafri has proved this in his book with authentic references. The fact has been established beyond any shadow of doubt and one did not expect an erudite writer like Irfan Javed to make such a mistake.

In the piece on Manto, he says that a law suit was filed in Karachi against Manto’s short story Thanda Gosht on the charges of obscenity (page 87). This needs some correction, too. Mehdi Ali Siddiqi in his autobiography Bila Kam-o-Kaast has described the case in detail (Karachi University, 2002, page 162-164). According to Siddiqi, the case was against a short story by Manto titled Neeche Ooper Aur Darmiyaan (though Manto was sued for Thanda Gosht too, but that was another case). After Manto’s death in January 1955, Siddiqi wrote a piece, describing the case. This piece, Manto’s own account of the case and Manto’s letter addressed to Siddiqi, too, were made parts of Siddiq’s book as appendices (pages 351-361).

Aside from such minor issues, the book is packed with some pieces of information on literature, arts and shed light on some hazy corners of the lives of writers and intellectuals. One of the most notable aspects of the book is that Irfan Javed has everywhere tried to defend the writers and has found some justifications for their behaviour, always showing empathy. This is quite contrary to what some of our writers and critics have been doing all along: scandalizing everything. This empathy shows his love for literature and those who create it.

Published in Dawn, October 5th, 2020

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.