Between 15 to 35 people end their lives in Pakistan every day.

That's as high as one person every hour.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that in 2012, the rate of suicide in Pakistan was 7.5 per 100,000 people. In other words, around 13,000 people killed themselves that year.

In 2016, the estimate was 2.9 per 100,000 i.e. over 5,500 ended their lives. Experts say the number of people dying is likely somewhere between the two figures, but the truth remains hidden.

This project hopes to end the silence by giving those who have suffered space to share their stories; by providing expert commentary and by providing access to a few resources the country has to offer those seeking help.

Trigger warning: The content that follows contains stories of suicide and suicide attempts, which may trigger some readers. Please proceed with caution and contact your mental health advisor in case of a crisis.

Suicide survey

To better understand the trends and context surrounding suicide in Pakistan, Dawn.com published an online survey in December 2018, asking respondents to anonymously share their views and stories about suicide. The non-scientific survey was published on the website and shared on social media, reflecting views of a segment of Dawn.com's readership, as captured in the respondent demographics outlined below.

The responses — 5,157 in total — provide a unique starting point to exploring the issue.

A few findings include:

38% of respondents said they personally know someone who has taken their own life.

43% said they personally know someone who has attempted suicide.

45% said they have thought about suicide but never acted on it.

9% said they have tried to end their lives.

1. Respondent demographics

A majority of those who took the survey are between 18-40 years old, male (72%), and from the three major cities.

2. Do you personally know someone who has taken their own life?

38% of total respondents said they knew someone who has taken their own life.

3. Do you know someone who has attempted suicide and survived?

Over 40% said they knew someone who had survived a suicide attempt.

4. Have you ever tried to end your life or thought about ending your life?

Respondents were evenly divided between those who have tried or thought of suicide, and those who have not. An additional 9% said they have tried to take their life.

5. Has someone ever spoken to you about having suicidal thoughts?

45% said they have had someone speak to them about feeling suicidal.

6. To what degree might the below causes lead someone to commit suicide?

Over half of respondents considered mental illness and financial troubles as 'high likelihood' reasons for suicide. Divorce was seen as having the lowest likelihood of resulting in suicide.

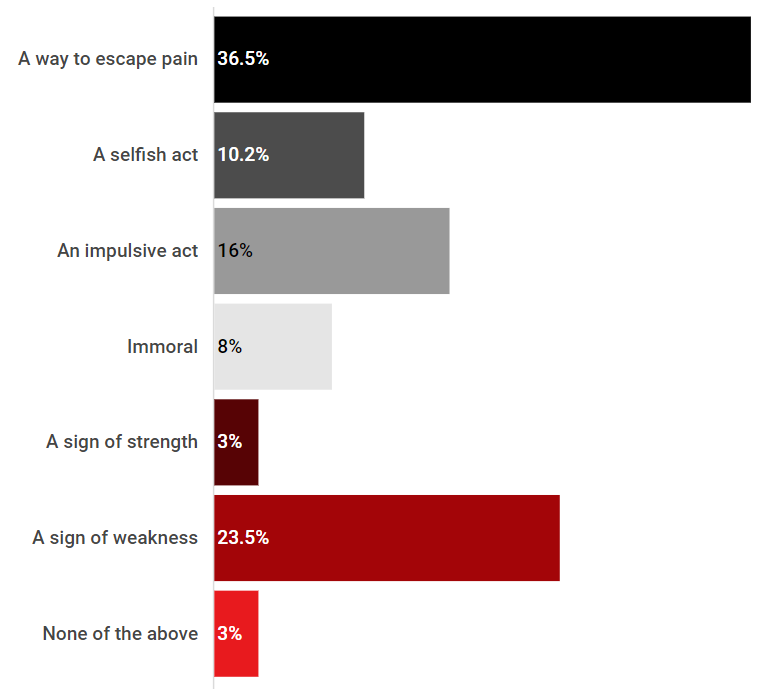

7. Which of the below describe your opinion of suicide? Select all that apply.

A low 8% of respondents considered suicide an immoral act. However, almost a quarter considered it a sign of weakness. The most common opinion was that suicide is, 'A way to escape pain'.

8. What barriers prevent a suicidal person from seeking help? Check all that apply.

The two barriers to seeking help that ranked highest are, 'Feeling like nothing will help' and, 'Lack of social support', followed closely by, 'Embarrassment or social stigma'.

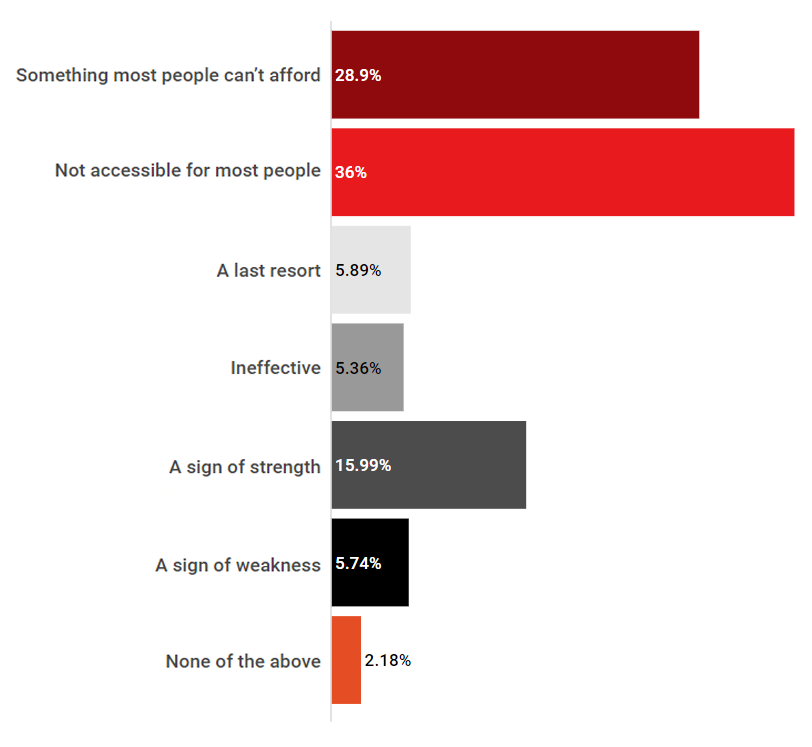

9. Please select all that apply: Seeing a mental health professional is...

The most common opinion from the statements is that seeking professional help is, 'Not accessible for most people'.

Let us open a dialogue about uncomfortable aspects of ourselves without shame. Let us be brave.

Losing our son

By Atiya Naqvi

Our son Emad died of a suicide on May 18, 2018 in Boston. He was working his dream job as a soccer coach in Boston. He had two FIFA licenses in coaching and was full of dreams and plans about his future. Emad was known for his wit and quirky humour and he was the life of a party amongst his very large circle of friends.

Our trip to Boston in a few hours is a harrowing blur of a long never ending flight where at times even the simple act of breathing was difficult. I was sure that my son had been a victim of foul play and so I and my husband were just grieving the injustice of our son losing his life just when everything seemed so promising and rosy.

However, once we got to Boston we were handed the note left behind by our son. It was clearly written in Emad’s own writing stating that this was a voluntary suicide and that he had left a video for his parents and two siblings on his phone to explain his reasons for ending his life.

Emad has left an almost two hour long video where he talks about his reasons for committing suicide.

He spoke about his teenage years when he was fat, when he was an average sports man, and an average student. He said he was always an A-grader but never an A-starrer. He says he felt he never made us proud and he was always someone who scraped through life in general. He said he always covered up his inadequacies with a wiseass attitude. He cited many examples of when he felt less than the others and every time we as parents were supportive of him he felt even worse for not being better than he was.

He went on to say that he started to feel different once he started to work as a soccer coach and changed his undergraduate major to pursue a career in soccer coaching. He said that he began to like himself and that he enjoyed the life he was now building for himself.

At the same time he couldn’t believe a mediocre person like him could achieve all that he had and so there had to be something wrong, which needed to be ended.

He ended the video by saying that he didn’t believe he was good enough, and that his current life of success and achievement was an illusion. He didn’t want this illusion to end and so he wanted to end his self-described “mediocre” life.

He was calm and loving throughout the video; there was no anxiety or fear on his face or in his demeanor. It was almost like a FaceTime conversation, except our beloved Emad was on longer on the other end of the phone. He couldn’t hear us sob or see the shock and devastation on our faces, he was gone — taking all his misguided beliefs of self-condemnations with him without realizing his worth.

In the months following my son’s passing I, his mother and a clinical psychologist, am now left with questions and no concrete answers.

A part of me died with Emad that day. As any mother would tell you, surviving your child’s death is a hell with no escape.

I struggle to think what the hardest part of my life is since my son left our world. The mornings when my eyes open to realize there is another interminable day ahead, my nights with no sleep till sheer exhaustion overtakes me, my responsibility towards my other two children, fear and self-doubt about myself as a mother, psychologist…. I could go on.

There is no end to this agony; at times I don't even want it to end as this is all I am left with.

In those dark hours, I turned to my training and then my faith. My training as a psychologist reconnected me back to my faith. After about three months of feeling utterly adrift in a dark space I returned to restructure my life. I read all I could about afterlife and grief, from a religious, psychological and spiritual perspective. I tried to accept my new reality without a fight, and replaced my WHY with a WHAT.

The new reality had no sleep, so I filled my nights with reading, praying and meditating. I worked on my own mental and physical health as best as I knew how. My friends and family were loving and supportive beyond imagination.

My life became about spending time with my husband and children. We valiantly tried to focus on Emad’s life and the person he was, instead of merely focusing on his last unfortunate choice. Each one of us tried to honour Emad’s life by devoting a part of our lives to carry his legacy.

My husband started Coach Emad Football Academy for underprivileged, but extremely talented children of Lyari. My daughter who is studying literature in Italy opted to write her thesis about death as she had experienced it. My youngest son joined his dad in organizing football matches at school levels to raise funds for the academy.

And I am raising awareness about suicide and depression by speaking openly about it in an environment where suicide is still a taboo topic. I am also in the process of starting support groups for grieving mothers so that broken and lost women like me can find ways to reconstruct our lives.

I have reflected long and hard on What happened to Emad and what might have been missed by me.

Where did we as parents go wrong? What are the causes of youth around the world caving into depression and suicide?

Emad never gave any signs of depression or even mood swings. He was always upbeat, helpful, and generally a very “good boy”. Yet all he believed was that he was just “not good enough”, he didn’t want to live the rest of his life as a mediocre person.

I feel it is very important for us as parents to start talking about OUR inadequacies. Let us do away with the dogma of perfectionism, competitiveness and overachievements and have an honest conversation about what roles and expectations we are creating.

We as parents have a language of validating achievements of our children and not the children themselves. The bars of achievements are getting higher and higher every day. The school systems are result-oriented and the average students slip through cracks unseen and unheard. These are the legacies that our youth are dumped with for the rest of their lives to carry. It is a heavy burden.

It is time to change the mindsets and language of us parents and our school systems. We have to look around our immediate environment of family, friends and colleagues and ask what kind of interaction did I have today? What did I see, hear and feel in each interaction? We simply cannot afford to know anything without experiencing it.

Each one of us will have to take responsibility for our interactions and communications in all our relationships that we care for. Let us take responsibility for our intrapersonal, interpersonal, professional and social interactions.

As a starter, if every parent, teacher, a friend is paying close, interested attention with empathy and compassion to those around us perhaps it might be easier for someone like Emad to open up and say he feels less than the others. Perhaps if the environment around our young people is less expectant, less judgmental they might not feel as if no matter what they do they haven’t made their parents proud.

The world is now a global village; there are unlimited opportunities of happy, healthy options of life. These options can seem out of their reach because our children are raised and educated mostly by adults of limiting beliefs.

Our next generation will benefit from growing in loving, acceptable environments in their homes, schools, workplaces and society in general so that they can make informed choices about their lives. They must have the space to make mistakes so they can learn; and our role can be to encourage, guide and support them to make newer and better choices.

Let us open a dialogue about uncomfortable aspects of ourselves without shame. Let us be brave and begin by holding genuine, trusting communications within our environment. It is time to stop pretending or wanting to be perfect. Let us work with Love and acceptance with the imperfect as our creator does with us.

The writer is a qualified clinical psychologist and clinical supervisor. She runs her own private practice, established 12 years ago.

Underlying many stories is a deep sense of isolation and shame, of suffering in silence, of fear of seeking help.

Dr's note

Murad Moosa Khan, Professor of Psychiatry at Aga Khan University

When Atika first contacted me for this project and explained she wanted me to review and comment on the testimonials in the section below, I didn't think it would be too much of an effort for me. After all, I have been practising psychiatry in Pakistan for more than a quarter of a century and had seen every type of mental disorder, of both genders, of all ages, from all sorts of backgrounds and from all parts of the country. And as suicide is my area of interest, one that I had been studying and researching for over 20 years, it would be interesting as well.

Little did I know what I was about to tread upon would be a window to the internal emotional struggles that so many Pakistanis are going through, without recourse to help. There were many who had no access to mental healthcare, others hesitated to seek help for fear of stigma, yet for others it was unaffordable.

The stories in the posts are extremely powerful and tell us what people in the highly complex and convoluted society of Pakistan are going through.

The testimonials are likely from the relatively well educated, English speaking, middle to upper-middle-class sections of the society. But reading about their struggles also gives us a clue what the not so well off in our society must be going through, with poverty, illiteracy, large family size, lack of space, drug use, unemployment and domestic violence all impacting their emotional health in ways one cannot even comprehend.

There are stories of bullying, of physical and sexual abuse, of rape, of domestic violence, of a toxic family atmosphere, of mental distress and of course, of self-harm and suicide. It is surprising how many of the more than 3,000 responses that were received, had either thoughts of suicide, had carried out self-harm acts themselves or knew of someone in their family or circle of friends, who had died by suicide.

Underlying many of these stories was a deep sense of isolation and shame, of suffering in silence, of fear of seeking help due to stigma or being judged.

The stories tell us how, under the veneer of socio-cultural and religious values, all kinds of ills — from rape to betrayal to bullying and drug use — exist in an ostensibly sanitised society. They tell us how the lack of education (not only literacy), of an organised health system and of law and justice put so many young Pakistanis at risk and affecting their mental health. The stories also tell us about the lack of mental health services in the country, the poor training, and poor ethical and professional standards of many of our mental health professionals and of the shame and stigma attached to seeking help for mental health problems.

The stories also tell us about the incredible resiliency of many Pakistanis, as they fight against insurmountable odds of the society and, at times their families, to not only survive but progress in life as well.

There are many unsung heroes in this country. Some are among those who have written in.

For years, we have witnessed neglect of social development in the country; of housing and transport, of health and education, of law and order, of justice. This has resulted in a population that is highly mentally distressed, with extremely high levels of stress. Some of this stress is played out on our roads, in our homes, in extreme kinds of behaviours including suicide and terrorism.

There is an urgent need to address the many ills in this society. We need to address the upstream factors such as social factors as well as downstream factors such as more and better mental health facilities, including suicide prevention activities. This is a human rights issue.

The people of this country deserve it.

Dr Murad Moosa Khan MRCPsych, PhD is a Professor of Psychiatry at Aga Khan University and the President of International Association for Suicide Prevention. He tweets @MuradMKhan

Suicide does not happen in a vacuum. There is a 'suicidal pathway' that people get on, which may start weeks or months before the event.

Testimonials

Shared below are experiences of dealing with mental illness narrated by respondents to our anonymous survey. The short stories have been thematically grouped, and contain observations by Dr Murad Moosa Khan, Professor, Dept. of Psychiatry, Aga Khan University.

Trigger warning: The following accounts, which include details of suicides and suicide attempts, may trigger some readers. Please proceed with caution and contact your mental health advisor in case of a crisis. Additionally, the comments made by the doctor should not be viewed as holistic advice or treatment. Please consult a mental health professional for a detailed evaluation.

RELATIONSHIPS

SEXUAL ABUSE

SELF-HARM

EATING DISORDER

TOXIC FAMILY

SEXUAL IDENTITY

FINANCIAL PRESSURE

SOCIETAL PRESSURE

LACK OF SUPPORT

ACADEMIC PRESSURE

BULLYING

It takes a special person and a special type of friendship to not give up on somebody who is feeling down.

Help

A contact list of mental health practitioners across Pakistan has been compiled and presented city-wise below. While this is not an exhaustive list, it may serve as a useful starting point for those seeking help.

Please email if you would like to recommend a name to be added to the list.

Note: Dawn.com does not endorse any health practitioner, and it is recommended that adequate research/background checks be conducted when approaching anyone listed here or otherwise. The contact list has been compiled using publicly available data from Counselling.pk, Taskeen.org, Marham.pk.

On mobile, please swipe left/right on table to see complete details

CREDITS

Project directors: Atika Rehman, Jahanzaib Haque

Associate producer: Shahbano Ali Khan

Illustrations: Mahenoor Raphick (profile)