In a state of shocked silence, Karachi watched bulldozers roam its streets, pulling down shops, buildings and nurseries considered illegal, reducing them to rubble in a matter of hours. While few dispute their legality — though for years a number of watchdog organisations have been highlighting encroachments on amenity plots, parks, pavements and illegal buildings — it’s the suddenness of it that caught everyone on the back foot.

It draws attention to the experience of other cities across the world, today admired for their modernity, smooth management and liveability. Looking at three cities — London, New York and Paris — gives important context to the current efforts in Karachi. All three cities amassed wealth and power through colonisation and trade in the 19th century, yet all three were dark, dingy, filthy and rampant with crime and poverty. In many ways, they presented a much grimmer picture than present day Karachi.

PARIS

The French Revolution (1789) had overthrown the French aristocracy, and the word “poor” was eliminated from the new political vocabulary, yet the most wretched poverty continued.

In 1845, French social reformer Victor Considerant wrote: “Paris is an immense workshop of putrefaction, where misery, pestilence and sickness work in concert, where sunlight and air rarely penetrate. Paris is a terrible place where plants shrivel and perish, and where, of seven small infants, four die during the course of the year.” A single room could have as many as 20 persons living in it. Its narrow streets were barely navigable by horse-driven carts and wagons.

Napoleon Bonaparte’s efforts at change were cut short by his exile. “If only the heavens had given me 20 more years of rule and a little leisure,” he wrote while in exile on Saint Helena, “one would vainly search today for the old Paris; nothing would remain of it but vestiges.”

In 1853, his nephew Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the first elected president, engaged Georges Eugene Haussmann to redesign Paris as the modern city we know today. Over 17 years, he gutted the old Paris, ran broad boulevards through it financed by real estate speculators, displacing 350,000 people and their businesses. He demolished 19,730 buildings, constructed 215,300 new apartments but rents increased by 300 percent. The rich occupied only three percent of residences, yet in the aftermath of the disruption, Paris saw the fastest population growth of the time.

The grim,dingy and crime-ridden past of London, Paris and New York lends a new perspective to the efforts to fix Karachi

While old Parisians, such as Victor Hugo, were dismayed, other Europeans were full of praise, calling Haussmann a brilliant modern urban developer. He developed broad avenues lined with new elegantly designed five-storey buildings with the now distinctive wrought iron balconies, city squares, parks, a comprehensive sewerage system, a new aqueduct for fresh water, a network of underground gas pipes for lighting streets and buildings, elaborate fountains, public lavatories and rows of newly planted trees, new railway stations, the Paris Opera House, new schools, churches, theatres, food markets and the iconic Arc de Triomphe with its 12 radiating avenues.

He engaged a large team of architects, engineers, labourers and landscape gardeners. It cost the equivalent of 75 billion euros. Yet when he retired he was living in a modestly rented apartment. He also demolished the house he was born in.

When Adolf Hitler gave orders for the wholesale demolition of Paris in 1944, the German military governor Major General Dietrich von Choltitz refused to obey. Paris was simply too beautiful to destroy.

LONDON

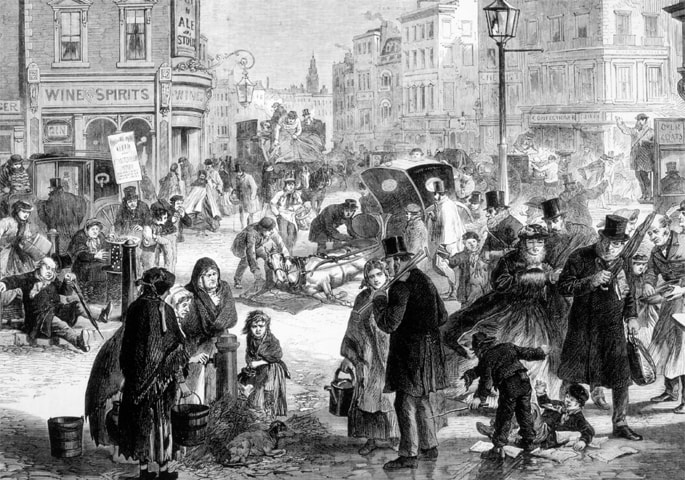

The streets of 19th century London were covered in the dung of horses, the air was filled with soot and smoke, and the Thames was full of human refuse and rubbish. A city of extremes like Paris, the slum areas of London were unliveable even by the 19th century standards.

Whole families were crammed into single rooms with communal cooking facilities. Those who could not pay rent slept in doss houses in beds called coffins, for a few pence. At half the price, they could sleep sitting with a rope strung across to lean over. Toilets were a few outhouses for large tenement buildings, leaking through the walls of adjoining homes. Water for cooking and laundry was provided by communal standpipes with people queuing and fighting to get their turn during the few hours it was available. Mixing of drinking water with sewage led to a cholera breakout in 1831, killing 6,000 people.

The unusually hot summer of 1858 came to be known as The Great Stink. The stench from River Thames was so strong that Parliament had to be held behind lime-soaked curtains. It galvanised legislation to find a solution to the sewage system. Joseph Bazalgette, an engineer with a background in land drainage methods, was hired, and history acknowledges his extraordinary feat of engineering.

In 1875, the Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Improvement Act gave local authorities powers to buy up, clear and redevelop slum areas, as well as requiring them to re-house inhabitants. The prosperous moved out of town centres to the new suburbs, while much of the housing for the poor was demolished for commercial spaces, or to make way for the railway stations and lines that appeared from the 1840s.

Ebenezer Howard proposed the Garden City concept to improve the quality of life, “the peaceful path to real reform,” a central city surrounded by satellite towns that linked nature to urban areas. It was to be funded by private companies — based on a system of five percent philanthropy — who would purchase large tracts of land for development of residences and infrastructure in trust for the future residents.

Unlike the 17 intense years of Haussmann’s reshaping of Paris, the clean-up of London took decades — interrupted, and to some extent aided, by the destruction of two World Wars that necessitated rebuilding on a wide scale.

NEW YORK

Streets of 19th century New York were full of rubbish, horse manure, dead animals, food waste and discarded household items, and reeked of human excreta. It was not until 1895 that the municipality started collecting rubbish. The soil cart men collected human soil from outhouses at night, disposing it into the surrounding waterways or in the harbour.

Journalist Jacob Riis took photographs of the slums of New York in the 1890s that shocked many Americans, with the images of extreme poverty at a time of great economic prosperity for the few.

The Five Points was a legendary slum in 19th century New York. It was known for street gangs, gambling dens, violent saloons and houses of prostitution that even shocked Charles Dickens.

The city was in the grip of unscrupulous developers, who held sway over all city matters, and cultivated police corruption.

The city was finally taken over by a new mayor, William Strong, who vowed to improve living conditions in New York. A Civil War veteran, George Waring, was asked to take over street cleaning. He said, “I’ll do it under one condition — you leave me alone. If you want to fire me, of course, that’s your right. But I will appoint and hire the people I feel are best for the job, not because they’re people you want to do favours for.” He created a militaristic management with specific tasks and areas for his crew, who had white uniforms to create the image of hygiene. Initially, there was hostility from the poor localities, and police protection was required, until residents began to appreciate cleaner neighbourhoods.

Women played a pivotal role. Well-to-do women motivated the poorer women who scavenged for food on the streets, as well as lobbying politicians.

Teddy Roosevelt, who later became President of America, took on reform of the police department. One of his first actions was to walk around the streets at night with journalist Riis, hauling up officers asleep on duty, which caused a sensation. In the heat wave, he made officers distribute ice. He constantly came into conflict with powerful, corrupt police officers who had amassed huge fortunes and hostile political groups. Burnt out, he left after two years, unable to make much headway. It was not until Roosevelt’s New Deal funding, in the late 1930s, and the strong mayorship of La Guardia, that infrastructural development and order finally came to New York.

Paris had the most radical makeover, with the whole city — other than the Marais — being entirely rebuilt. London made changes through a continuous process of legislation. New York transformed through engagement with the citizenry.

Each city has some aspect of their problems that will be familiar in the context of Karachi. All three cities transformed themselves into modern cities by the middle of the 20th century, with the state taking responsibility for ensuring their functionality.

As times have changed, it is probably no longer possible to take an authoritarian approach. The economy of cities has also changed considerably. The Belgium-based Cities Alliance — a global partnership formed jointly by the World Bank and the United Nations Centre for Human Settlements — addresses the issue of slums with a number of suggestions.

Rural development as an alternative to movement to urban centres is seen as ineffective. It rejects the displacing of the poor to the suburbs or edges of the city and instead recommends improving the infrastructure by engaging with communities and giving them a stake in development so that eviction is not a fear. Their experience shows that upgrading slum areas promotes economic development, inclusivity, improves quality of life, reduces poverty and health issues, and thus raises the value of the city as a whole.

Clearly, there are many alternatives and complexities to be considered by those reshaping Karachi to avoiding replacing one type of chaos with another, and ensuring economic sustainability and quality of life.

Durriya Kazi is a Karachi-based artist and heads the department of visual studies at the University of Karachi

Email: durriyakazi1918@gmail.com

Published in Dawn, EOS, March 3rd, 2019