The government is telling us that the economy has now bottomed out and from here it will be on the upswing towards the path of recovery. The argument is that they have made arrangements from “friendly countries” to plug the external financing gap of $12 billion, and Pakistan’s external sector is showing improvement as exports and remittances start to climb. On top of this, they claim, the depreciation of the rupee and hikes in the interest rate will further help the recovery in the external sector as the economy adjusts to a low foreign exchange level.

But financial markets do not seem convinced. Studying the bets that banks place in government debt auctions is perhaps the best indicator of how markets see the direction of the economy. If this indicator is anything to go by, then the year 2018 has seen some of the most cautious and restrained bets from the financial markets in almost a decade. This is because of the prevailing uncertainty which shows no sign of diminishing. In short, the government is trying to declare victory in its battle with the country’s external deficit, but markets remain sceptical of the claim.

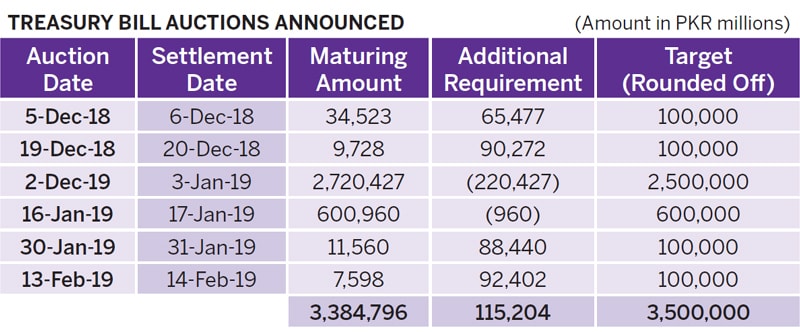

Here is how it works. Every fortnight, the government enters the financial markets to borrow a certain amount of money as per a predetermined calendar. Both the dates of the auctions and the amount the government is seeking to borrow are announced well in advance by the State Bank, which conducts the auctions (see table above).

The auctions, known as T-bill auctions, last for two hours starting at 10am, and are conducted electronically. Only authorised dealers in government debt securities are allowed to participate, usually commercial banks (excluding Islamic banks because government debt is interest-based). There are three tenors (as the timeframes are called) offered: 3 months, 6 months and 12 months. This basically means that if a party puts a certain amount of money in a 3-month tenor (to take an example), then, after three months they will be given their money back plus whatever yield was offered at the time of the auction.

Government claims notwithstanding, financial markets seem to lack confidence in a quick recovery. All you have to do is look at Treasury bill auctions

The government announces the amount it seeks to lift from the market in each auction, and keeps a sealed “cut-off yield” which is not shared with the participants. The ‘cut-off yield’ is basically the highest interest the government is willing to pay in each tenor, and since auction participants do not know in advance what cut-off yields have been decided for each tenor, they are left to guess. When they submit a bid, they have to say how much money they will offer at what yield. If the yield demanded is higher than the cut-off yield, then the bid is discarded. Only those bids below the cut-off yield are admitted.

In this way, the market players are pitted against each other in offering their money to the government at the lowest possible yield. Since government debt is the safest kind, all banks are keen to land successful bids, but they are equally keen to get a deal as close to the cut-off yield as possible. Government debt is also attractive because it has a secondary market, so any bank that holds treasury bills (the paper that government debt is denominated in) can sell those bills to any other bank at any given time.

How banks behave in T-bill auctions is largely an untold story of our economy. Yet this behaviour is an important barometer of market sentiment and how much confidence the markets have in the future direction of the economy. When one sees vibrant participation in government debt auctions, particularly in the longer tenors, it is an indicator that the financial market sees stable returns over a longer time horizon. But if there is lacklustre participation, and most bids are concentrated in short-term tenors, it can be read as a sign that the financial markets see instability ahead and do not wish to place bets beyond a short time horizon for fear of being caught out short.

So, what are the markets telling us?

One of the biggest fears of the markets is that they will pick up government bonds at a given yield today and the State Bank will raise interest rates before that bond matures. In the example from the latest auction on December 5 (see table below), if the State Bank raises rates by another one percent in its next monetary policy decision due in January, the discount rate will rise to 11 percent whereas the banks will be holding two trillion rupees worth of debt that is giving them a yield of around 10.3 percent. The amount that they stand to lose as a result could be considerable, and the risk weighs heavily on their mind depending on the economic outlook.

When the economy is growing and its various deficits are contained, the outlook on interest rates is also stable and banks feel safer venturing into longer tenor bonds for the stable returns over a longer time horizon. But when the economy begins to falter, inflationary pressures become apparent, the deficits begin to grow to a point where they no longer look sustainable, and markets begin to suspect that the government will have no choice but to resort to drastic corrective action such as interest rate hikes and currency devaluation, they will abandon longer tenor bonds and crowd around shorter term debt.

This is exactly what has happened all through 2018. Consider this: in the year 2017, from January till December 25, T-bill auctions were held and the yield on 3-month bonds rose by 0.0267 percent in the entire year. Other tenors, in 6 and 12 months, also saw meagre increases in yields during this time. This was the case in preceding years, too.

But in the year 2018, in the 25 auctions held between Jan 4 till Dec 5, the yield on 3-month bond rose by 4.276 percent — a near doubling in one year alone. This sharp increase is driven by the massive interest rate hikes that the State Bank began administering this year, and markets are wondering how much further there is to go.

The cycle of interest rate hikes began in January 2018 when the State Bank raised the policy rate by a meagre 25 basis points (bps), or 0.25 percent “in order to preempt overheating of the economy and inflation breaching its target rate.” The next hike came in May, this time slightly larger increase of 50bps followed by another hike of 100bps in July and another 100bps in September. After the latest hike of 150bps in November, the policy discount rate of the State Bank went from 5.75 percent at the start of the year to 10 percent by November. Now the markets are in fear of what will happen in the next monetary policy announcements due in January and May of 2019 respectively.

In response to this cycle of interest rate hikes, banks abandoned longer tenors and rushed into 3-month bonds instead. In the last 26 auctions, starting from the one on Dec 20, 2017, no successful bids were placed in 6- and 12-month bonds in all seven auctions. In fact, no bids were placed in 12-month bonds at all throughout this period, indicating that markets could not see what will happen over one year, and were very reluctant on the outlook even for 6 months. Almost all the money the government picked up in these auctions was in 3-month bonds. Nobody was willing to go any longer with the government with any substantial amount.

There were good reasons for this reticence. This was, after all, the year it all blew up — the three years of real sector growth that former finance minister Ishaq Dar used to boast about. This was the year Pakistan ran a record $18 billion current account deficit, when its reserves ran down to barely being able to cover more than one month’s imports, when it was forced to approach the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and, very importantly, when it was left largely rudderless due to the political storms raging in the run-up to the elections, and the appearance of a new government after the election that said it needed 100 days to find its feet.

The auction on December 5 was the first to be held after those 100 days were over, and although there was healthy participation owing mainly to another massive 150bps increase in interest rates by the State Bank only days earlier, all the bids were again concentrated in 3-month bonds.

The clouds of uncertainty have clearly not parted. If the mood of the markets has not changed despite assurances from the government that they have found the resources to plug the external financing gap for this year, and despite growing hikes in interest rates, then the next auction scheduled for Dec 19, 2018, should show diminished participation. At the moment the government is expecting to lift 90 billion rupees in fresh borrowing from that auction. If the markets feel that the economy has more adjustment to undertake, that interest rates could rise substantially one more time in the January or May monetary policy decision, then the amounts bid will be smaller than they were on Dec 5 and will continue to be concentrated in 3 month tenors.

Since markets are cold and calculating, and totally impervious to hype, their sentiments are a good barometer of how successfully any government has managed to command business confidence in the economy. The government can sell its story of having pulled the economy out of its downswing by securing external financing, but whether or not the markets buy this story will be the real test.

The writer is Dawn’s Business Editor

Published in Dawn, EOS, December 16th, 2018