Earlier in the year, I was invited to the launch of a literary review titled The Aleph Review at the home of its publisher and editor-in-chief, Mehvash Amin. In the midst of a conclave of the Lahore Cantonment’s towering, old trees, a warm, spring breeze, and the whiff of a sticky sweetness from hundreds of flowers, Amin launched the Review, an anthology of English literature by Pakistani poets spanning the history of the country and its breadth of skill — ranging from poetry to interview to humor to prose.

Intrigued by the freshly-minted, glossy-paged Review in my hand, I delved into Taufiq Rafat’s seminal essay titled ‘Defining the Pakistani Idiom’. Rafat is featured on the cover of the Review, dedicated to him as the ‘Father of the Pakistani Idiom in English Poetry’ and, on a personal level, as Amin’s late mentor. Rafat’s ‘Pakistani idiom’ uses image-filled language to demonstrate a Pakistani sensibility. Esteemed academic Shaista Sirajuddin, whose essay ‘Taufiq Rafat’s Use of Language’ is in the Review, describes Rafat’s ‘Pakistani idiom’ as including “images which, while fresh and vivid, are carefully modulated to ensure that the overall effect is one of the ordinary and familiar, so that the writing steers clear of romanticism and conventional poeticising.”

“If you record your experiences in poetry while being true idiomatically to your own surroundings, there is a veracity and truthfulness to the writing,” Amin says about what Rafat taught her as her mentor during her days studying English literature at Lahore’s Kinnaird College for Women. Truthfulness, a certain honesty in the pursuit and subsequent execution of what one loves, is the driving force and standout quality of the Review. Poets both old and new breathe life into pages upon pages of poetry. Not only do the likes of Adrian Hussain and Ilona Yusuf make an entrance, but one discovers newer stars like Kyla Pasha and Afshan Shafi. In a line from Shafi’s poem ‘What They’re Looking for in a Girl’ – “some require the sleek and wondrous /textile of her to be not unlike/ a kind of molasses /where one desires the July concertina /of her bruised and rambunctious aspect /more than the manner of her manner” – she speaks to women in a way few can outside the ‘Pakistani idiom’.

Moving on to prose, the Review does not have as much fiction as it does poetry, but it makes up for it with attention to diversity of form with an assortment of essays, fiction, humour, screenplays, reportage, and even an obituary. In the fiction section, Zulfikar Ghose makes an entrance. In memoirs, Soniah Kamal's ‘A Love Story, Too’ about a Pakistani woman who proposes to her love interest after meeting him on the internet is sharp and witty, with simple, effective language and storytelling that grips the reader. Shahbaz Taseer ’s ‘The First Phone Call’ about the first (and then believed to be the last) moment he spoke to his family after being kidnapped is moving in the most visceral way. He writes: “At this moment I found a strange strength … ‘I fear no man, I only fear you. I beg from no man, I only ask from you,’ I intoned. It’s funny how strong you can stand in the face of tragedy when you feel God is with you. I believed with all my heart that He was with me… ”

This is a literary review but a love of art is running parallel. Much like the writers, the featured artists range from the renowned to the upcoming: Anam Hummayun to Saeed Akhtar to R M Naeem to Noor Mahmood. Amin’s mother, Jamila Masud , was an artist and sculptor, and Amin believes the artwork in the Review “corroborates the story alongside which it was placed”. The Review is a textual and visual treat; it brings lovers of words as well as art together in an ode to creativity. “The Review is my way of encouraging young people – what I was decades ago – to be printed alongside published authors. I hope that encourages them to write and avoid the circumambulating journey that I had to take to get to exactly the point that I started from.”

Amin, who has been editor of English-language magazines Libas and Hello! Pakistan, says she would write fiction any time she had outside of her work and raising her children, but did not know how to publish or sell her writing until a friend forced her to send it to journals. She hopes to fill the gap: “Prose is definitely preferred over poetry. Poets can only hope to be published in literary journals, or getting their chapbooks published. The Review is very indulgent about poetry, and hopes to project good poets!” In a literary world in which few established writers make time for mentorship, Amin’s idea is a noble one that appears to originate, in part, from the influence of her own mentor Taufiq Rafat.

The Aleph Review has come to us at a time when established writers appear to be doing well but younger ones have no mentorship, no place for publishing new writing in Pakistan apart from poor-quality publications printed once every few years that no one bothers reading, and no chance of hoping to turn any sort of writing talent into a tenable profession. With Mehvash Amin at the helm of The Aleph Review, one hopes her talent, the quality of the Review, and her will to create a haven for those who love to write and those who love to read brings forth a new age of writing.

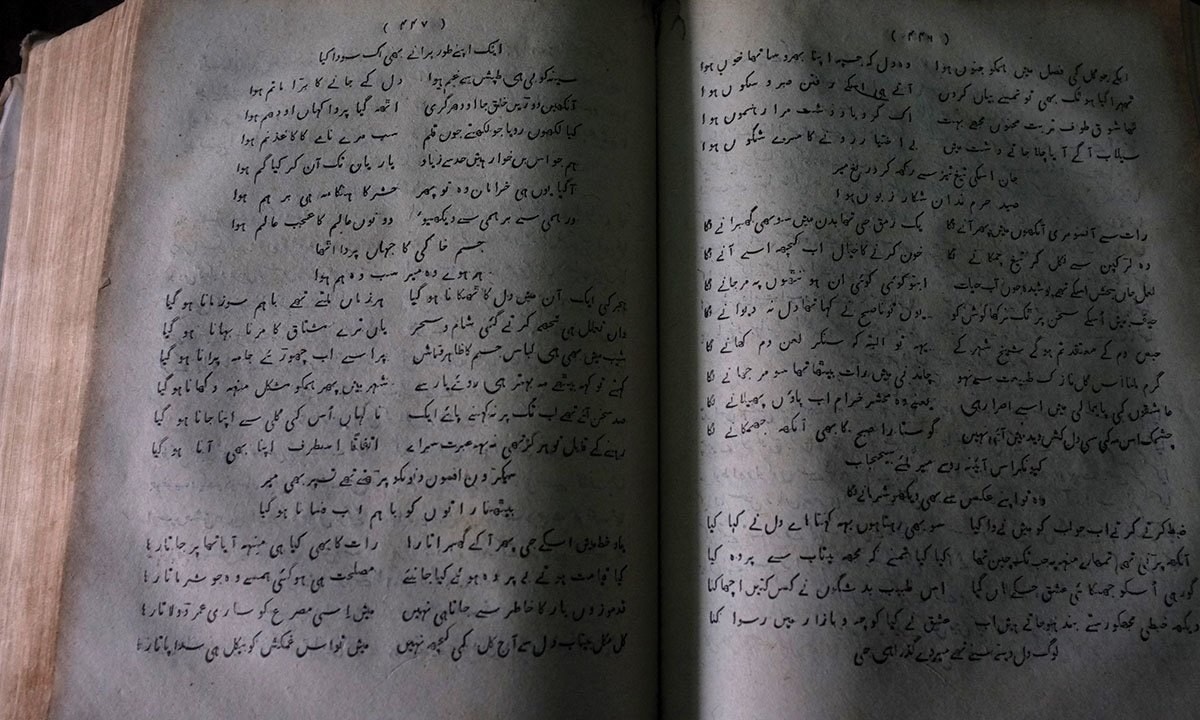

At the moment, Amin and her team are busy compiling a second issue. It will have a lot of what made the first one special; and more: more languages (a graphic story translated from Urdu and Punjabi mahiyas), more colour and more writers from South Asia and the world.

A previous version of this review stated that Soniah Kamal's 'A Love Story, Too' falls under the Review's fiction section. Kamal's story is a memoir and a work of non-fiction. We apologise for the error.