Manchar Lake: Toxic water, dead fish fill Asia’s largest freshwater body

Fishing communities can no longer survive on Asia’s largest freshwater lake after a massive artificial drain has contaminated water and destroyed fish stocks

A lifetime spent in a houseboat may seem extraordinary to many, but for 101-year old Haji Wali Mohammad it is the only way of life he knows. Mohammed and his family of 500 people live on 48 houseboats that form a village — also known by his name — on Manchar Lake in Sindh.

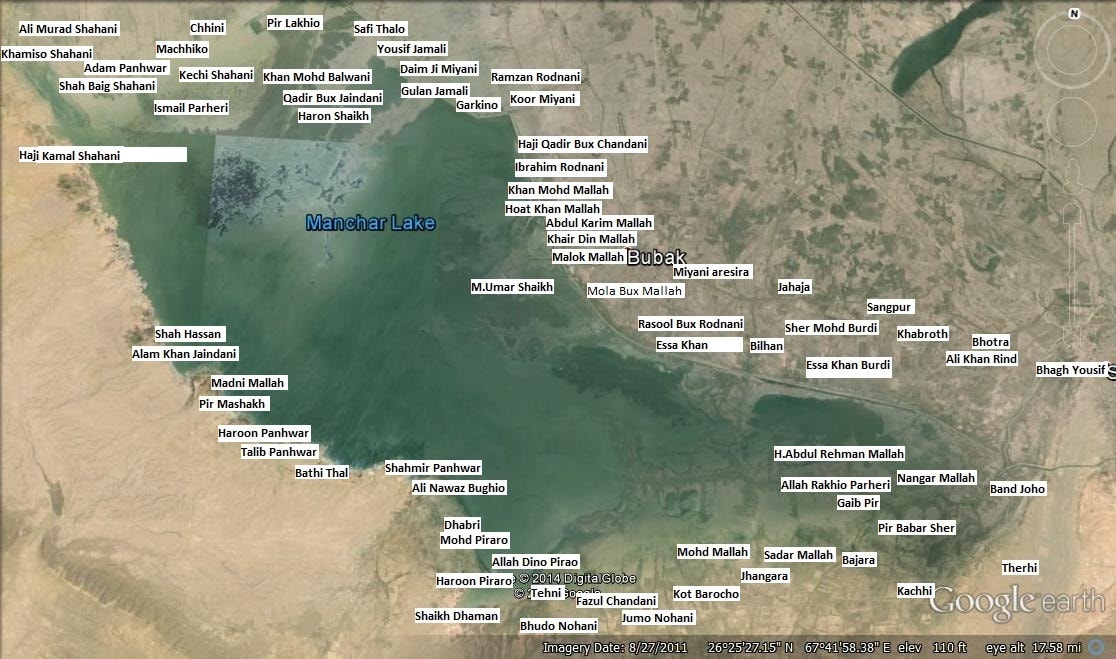

Manchar is one of Asia’s largest freshwater lakes, spread over 200 square kilometres it expands to as much as 500 square kilometres during the monsoon rains. The average depth is between 2.5 to 3.75 metres.

Mohammad belongs to the Mohana indigenous fishing community, who have lived on Manchar lake for as long as he can remember. “My father, my grandfather and even his father all lived and died here,” the fisherman gestured to the vast lake. “And I will too,” said the centenarian resolutely, as his gnarled fingers moved over rosary beads.

In contrast, Mohammad’s eleven-year-old grandson, Allah Wasaya, does not want to live on the boat when he grows up. “There’s nothing to do here after dark,” he said. He has had a taste of life on the land where his movement isn’t restricted and he can play without getting wet.

His grandfather is worried about the family’s future. Barrages and dams have reduced the flow of fresh water into the lake on the one hand, and waste water from industry and agriculture in the north on the other has led to the slow ecological demise of the lake.

The polluted and increasingly saline water has made it difficult for fish to survive. “We had a good life; we caught so many fish that there were not enough buyers,”Mohammad said. “Today, we cannot catch enough fish for three square meals for our own children.”

His beautifully hand-carved wooden houseboat is now dilapidated and barely able to accommodate his eldest son’s rapidly expanding family of 12. His other two sons also live on boats next door with their own large families.

Saying goodbye to traditional occupation

Annual fish catch on the lake has dropped dramatically from 2,300 metric tonnes in 1944, to 700 million tonnes in the 1980s, said Mustafa Mirani, vice chairman of the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum, an NGO working to promote the rights of the local fishing community. “Today, it is no more than 75 million tonnes,” he estimated.

Fourteen of the 200 species of fish found in the lake back in 1930 have become extinct, according to a 1999 survey conducted by Sindh Education Foundation.

As part of the Indus Flyway, birds from Central Asia in the north stopped at Manchar on the way to warmer south. According to a report by Friends of Indus Forum, in 1988, a total of 50,000 birds representing 102 species of migratory and resident birds were recorded. The lake is home to 29 species of aquatic plants, 11 tree species and 17 varieties of crops.

The Mohana are now fighting for their survival. “The commercially profitable fish have all but gone,” said Mirani. The remaining fish, locally known as ‘dhayya’, is sold for Rs 5/kilogramme and is dried and pounded into a powder to be used as chicken feed, he said.

Many boat people have been forced to sever their ties with the lake and move onto the embankments. With no education or way to earn a living apart from fishing, the once prosperous and proud community now lives in poverty with no clean water for drinking or washing.

Maula Baksh Mallah, 60, moved to the land some 30 years ago. “There just wasn’t enough catch,” he said. He recalled the time when the fishermen caught so much fish that there was always enough left over to give to passersbys.

Naseer Memon, chief executive of the Islamabad-based Strengthening Participatory Organization (SPO), grew up in the city of Dadu in Sindh. He recalled Bubak town on the edge of the lake in the 1990s: “The railway station was a small but lively where fishermen would quickly load fish to be taken to cities as far as Lahore.”

Today, the same station is a forlorn sight and trains whistle by without stopping.

Forced exodus

There are now only 4,000 to 5,000 people living on the lake, compared to 20,000 back in the 1980s when the “water was sweet” Mustafa Mirani estimates, though Pakistan has not carried out a census since 1998.

“Many fishermen go to Gwadar and Pasni in Balochistan to fish in the sea now,” said Yusuf Mallah, Wassaya’s father who works at the Karachi Fisheries Harbor Authority. “Fishing in the sea is more difficult as it means going into deep water and being able to survive the strong winds and storms,” he said.

Mohanas used to migrate temporarily to nearby land when the lake swelled, said Mirani, who has been carrying out research on Manchar for over 20 years. As the fish catch declined these temporary shelters became more permanent.

"Today there are as many as 25,000 living in villages dotting the lake."

Water, water everywhere, not a drop to drink

Children and women are always falling sick because of the toxic concoction surrounding them which is used for bathing, washing clothes and utensils. Tuberculosis, skin diseases and eye infections leading to blindness are now common, according to Mirani.

Wasaya says he will become a doctor. “Somebody or the other in my family is always sick. It’s either high fever, headache or some stomach bug,” he said and added: “It takes a long time to get to the doctor.”

Wasaya’s father says they get 60 litres of water every day from the 20 filter plants installed by the government on the mainland some five years ago. He has to pay Rs 15 for a donkey cart to carry each 30-litre jerry can onto his boat. “But it has to be used frugally and is used strictly for drinking and for cooking purposes only,” he said.

All photos by author

This article was originally published on The Third Pole and has been reproduced with permission.